Battle of Salamis

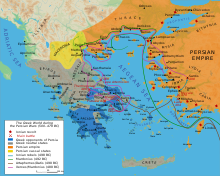

The battle was fought in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens, and marked the high point of the second Persian invasion of Greece.

Although heavily outnumbered, the Greeks were persuaded by Athenian general Themistocles to bring the Persian fleet to battle again, in the hope that a victory would prevent naval operations against the Peloponnese.

The Greek city-states of Athens and Eretria had supported the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt against the Persian Empire of Darius I in 499-494 BC, led by the satrap of Miletus, Aristagoras.

[13] A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the conquest of Thrace and forced Macedon to become a client kingdom of Persia.

[15] Darius thus put together an amphibious task force under Datis and Artaphernes in 490 BC, which attacked Naxos, before receiving the submission of the other Cycladic Islands.

[17] Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.

[19] Xerxes decided that the Hellespont would be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos (rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC).

[20] By early 480 BC, the preparations were complete, and the army which Xerxes had mustered at Sardis marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridges.

[26] However, once there, they were warned by Alexander I of Macedon that the vale could be bypassed through the pass by the modern village of Sarantaporo, and that the army of Xerxes was overwhelming, so the Greeks retreated.

En route Themistocles left inscriptions addressed to the Ionian Greek crews of the Persian fleet on all springs of water that they might stop at, asking them to defect to the Allied cause.

In a council-of-war called once the evacuation of Athens was complete, the Corinthian naval commander Adeimantus argued that the fleet should assemble off the coast of the Isthmus in order to achieve such a blockade.

[39] Artemisia, queen of Halicarnassus and commander of its naval squadron in Xerxes's fleet, tried to convince him to wait for the Allies to surrender believing that battle in the straits of Salamis was an unnecessary risk.

[38] Clearly though, at some point just before the battle, new information began to reach Xerxes of rifts in the allied command; the Peloponnesians wished to evacuate from Salamis while they still could.

[42] Alternatively, this change in attitude amongst the Allies (who had waited patiently off the coast of Salamis for at least a week while Athens was captured) may have been in response to Persian offensive maneuvers.

[43] Themistocles claimed that the Allied command was in-fighting, that the Peloponnesians were planning to evacuate that very night, and that to gain victory all the Persians needed to do was to block the straits.

[51] The Allied navy was thus able to prepare properly for battle the forthcoming day, whilst the Persians spent the night fruitlessly at sea, searching for the alleged Greek evacuation.

[85] Time was now of the essence for the Persians – the huge invasion force could not be reasonably supported indefinitely, nor probably did Xerxes wish to be at the fringe of his empire for so long.

[86] Thermopylae had shown that a frontal assault against a well defended Greek position was useless; with the Allies now dug in across the narrow Isthmus, there was little chance of conquering the rest of Greece by land.

It seems probable that the Persians would not have attempted this unless they had been confident of the collapse of the Allied navy, and thus Themistocles's subterfuge appears to have played a key role in tipping the balance in the favor of the Greeks.

[42] Xerxes had also positioned around 400 troops on the island known as Psyttaleia, in the middle of the exit from the straits, in order to kill or capture any Greeks who ended up there (as a result of shipwreck or grounding).

Since they were not planning to flee after all, the Allies would have been able to spend the night preparing for battle, and after a speech by Themistocles, the marines boarded and the ships made ready to sail.

[103] Aeschylus claims that as the Persians approached (possibly implying that they were not already in the Straits at dawn), they heard the Greeks singing their battle hymn (paean) before they saw the Allied fleet: ὦ παῖδες Ἑλλήνων ἴτε ἐλευθεροῦτε πατρίδ᾽, ἐλευθεροῦτε δὲ παῖδας, γυναῖκας, θεῶν τέ πατρῴων ἕδη, θήκας τε προγόνων: νῦν ὑπὲρ πάντων ἀγών.

[103] Triremes were generally armed with a large ram at the front, with which it was possible to sink an enemy ship, or at least disable it by shearing off the banks of oars on one side.

In her desire to escape, she attacked and rammed another Persian vessel, thereby convincing the Athenian captain that the ship was an ally; Ameinias accordingly abandoned the chase.

[85] Herodotus tells us that Xerxes held a council of war, at which the Persian general Mardonius tried to make light of the defeat: Sire, be not grieved nor greatly distressed because of what has befallen us.

It is not on things of wood that the issue hangs for us, but on men and horses...If then you so desire, let us straightway attack the Peloponnese, or if it pleases you to wait, that also we can do...It is best then that you should do as I have said, but if you have resolved to lead your army away, even then I have another plan.

[133] Mardonius retreated to Boeotia to lure the Greeks into open terrain and the two sides eventually met near the city of Plataea (which had been razed the previous year).

[87] After Salamis, the Peloponnese, and by extension Greece as an entity, was safe from conquest; and the Persians suffered a major blow to their prestige and morale (as well as severe material losses).

[139][4][95][97] In a more extreme form of this argument, some historians argue that if the Greeks had lost at Salamis, the ensuing conquest of Greece by the Persians would have effectively stifled the growth of Western Civilization as we know it.

[140] This view is based on the premise that much of modern Western society, such as philosophy, science, personal freedom and democracy are rooted in the legacy of Ancient Greece.