Battle of Shiloh

After the surprise and lengthy Union casualty list became known, Grant was heavily criticized; in fact, decisions made by both the Federal and Confederate high command were afterward questioned by individuals on and off the battlefield.

[14] General Albert Sidney Johnston, Confederate commander of the Western Theater, made the controversial decision to abandon the region.

[16] The town of Corinth had strategic value because it was at the intersection of two railroads, including one that was part of the rail network used to move Confederate supplies and troops between Tennessee and Virginia.

Inexperience and bad weather caused their 20-mile (32 km) march north to be "a nightmare of confusion and delays", and the Confederate Army was not deployed into position until the afternoon of April 5.

A few thousand of the highly accurate Enfield rifles had been distributed to Johnston's men before the battle;[57] the supply of these increased as they were seized from Union troops in combat.

[69] Hardcastle kept most of his men in the southeast corner of James J. Fraley's 40-acre (16 ha) cotton field, while two sets of pickets were positioned closer to the Union camps.

[75] Peabody's patrol, with Powell leading, partially ruined the planned Confederate surprise and gave thousands of Union soldiers time (although brief) to prepare for battle.

[82][Note 8] Facing artillery fire and a frontal attack from the corps of Hardee, Bragg, and Polk, Sherman's men performed reasonably well—if they fought.

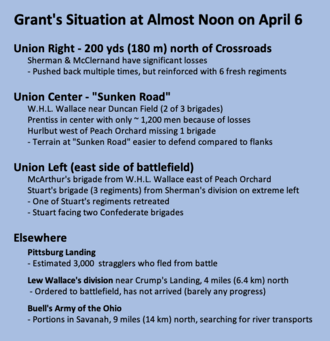

Hurlbut brought his remaining two brigades south on the Hamburg-Savannah Road near Wicker Field, and he encountered a large number of panic-stricken men from Prentiss's division who were fleeing north.

[96][Note 9] Grant ordered Bull Nelson to march his division along the east side of the river to a point opposite Pittsburg Landing, where it could be ferried over to the battlefield.

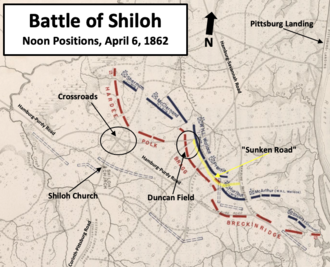

With reinforcements, the Confederate forces began a bayonet charge at about 1:00 pm that pushed McClernand and McDowell back to their original counterattack line at Jones Field.

[135] Captain Andrew Hickenlooper's 5th Ohio Independent Light Artillery Battery used shrapnel and canister to stop the first charge, and Confederate losses were considerable.

[137] Among the Union soldiers killed was Major James Powell, who led the early morning patrol that discovered the Confederate army at Fraley Field.

[156] At 2:50 pm, Lieutenant William Gwin, commander of the USS Tyler, put his gunboat into action by firing on the Confederate batteries near the Union left.

[161] Sometime in the late afternoon, Grant assigned Colonel Joseph Dana Webster, a veteran of the Mexican–American War, the task of setting up a defensive position at Pittsburg Landing.

[176] In his report, Ruggles claimed responsibility for assembling the batteries, but multiple people may have been involved—including Major Francis A. Shoup (Hardee's artillery chief) and Brigadier General James Trudeau.

[186][Note 20] By the time the Hornet's Nest fell, Grant's men had a defensive line from Pittsburg Landing to the Hamburg-Savannah Road and further north.

Cunningham wrote that Beauregard's critics ignore "the existing situation on the Shiloh battlefield"—including Confederate disorganization, time before sunset, and Grant's strong position augmented by gunboats.

[198] Daniel wrote that the thought that "the Confederates could have permanently breached or pulverized the Federal line in an additional hour or so of piecemeal night assaults simply lacks plausibility.

[204] The original Confederate plan was to push Grant's army away from Pittsburg Landing, and pin it against the northern creeks where it could not move quickly or get resupplied.

[40] Since most of the Union camps had been captured, these hungry and tired men would have to sleep in the open without blankets, and rain and cold weather added to their misery.

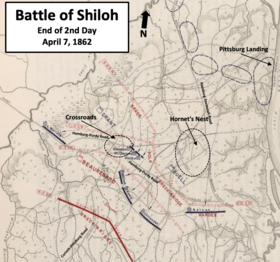

[208] The Union line from west to east consisted of the divisions commanded by Lew Wallace, Sherman, McClernand, Hurlbut, Crittenden, and Nelson.

The skirmishers that Nelson had chased off earlier were Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalry regiment and small portions of Chalmers's Brigade from Withers' division.

[221] On Grant's side of the battlefield, Sherman and McClernand were stopped at noon when Cheatham's Confederate division attacked east of the crossroads and north of Water Oaks Pond.

[225] Despite light opposition at his front, Lew Wallace put his division in a defensive position, and did not resume the offensive until Sherman and McClernand had pushed back Cheatham's attackers.

[227] All morning, Beauregard hoped that the arrival of 20,000 men under the command of Brigadier General Earl Van Dorn would change the battle momentum back to favoring the Confederates.

On the right, a group led by Forrest attacked Sherman's men as they were clearing fallen timber near a small creek, causing some of them to run for their lives.

The initial perception was that only "untoward events" had saved the Union army from destruction, and the withdrawal to Corinth was part of a strategic plan.

[262] With the loss at Shiloh, the likelihood of the Confederacy regaining control of the upper Mississippi Valley was severely diminished, and the large number of casualties represented the start of an unwinnable war of attrition.

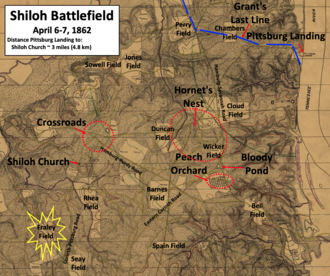

[272] Additional points in the park include Fraley Field, the Peach Orchard, Ruggles' Battery, Grant's Last Line, and the site of Johnston's death.