Battle of Vittorio Veneto

The city's name was officially changed to Vittorio Veneto in July 1923,[13] about nine months after Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party had ascended to power.

Diaz reorganized the troops, blocked the enemy advance by implementing defense in depth and mobile reserves, and stabilized the front line around the Piave River.

[citation needed] In June 1918, a large Austro-Hungarian offensive, aimed at breaking the Piave River defensive line and delivering a decisive blow to the Italian Army, was launched.

The whole offensive, which became known as the Battle of the Piave River ended in a heavy defeat for the imperial army, with the Austro-Hungarians losing 11,643 killed, 80,852 wounded and 25,547 captured.

[15] On 1 November, the new Hungarian government of Count Mihály Károlyi decided to recall all of the troops, who were conscripted from the territory of Kingdom of Hungary, which was a major blow for the Habsburgs' armies.

Lord Cavan's army consisted of two British and two Italian divisions, and they too were expected to cross the Piave by breaking the Austrian defenses at Papadopoli Island.

[20] The Allies:[21][22](Armando Diaz) Austria-Hungary[25] As night fell on 23 October, leading elements of Lord Cavan's Tenth Army were to force a crossing at a point where there were a number of islands.

[26] The British troops detailed for the night attack were the 2/1 Honourable Artillery Company (an infantry battalion despite the title) and the 1/ Royal Welch Fusiliers.

These troops were helpless to negotiate such a torrent as the Piave and relied upon boats propelled by the 18th Pontieri under the command of Captain Odini of the Italian engineers.

On the misty night of the 23rd, the Italians rowed the British forces across with a calm assurance and skill which amazed many of those who were more frightened of drowning than of fighting the Austrians.

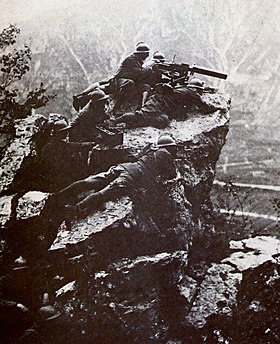

[27] In the early hours of 24 October, the anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of Caporetto, Comando Supremo launched the splintering[clarification needed] attack on Monte Grappa designed to draw in the Austro-Hungarian reserves.

The flooding of the Piave prevented two of the three central armies from advancing simultaneously with the third; but the latter, under the command of Earl Cavan, after seizing Papadopoli Island farther downstream, won a foothold on the left bank of the river on 27 October.

[29] The first days of the battle involved heavy artillery dueling between the two sides, which were fairly evenly matched in firepower, with the Italians possessing 7,700 guns to the Austro-Hungarians' 6,000.

[citation needed] On 29 October, the Italian Eighth Army pushed on towards Vittorio Veneto, which its advance guard of lancers and Bersaglieri cyclists entered on the morning of the 30th.

Carrying a resolza knife and two hand grenades, they were trained to remain in the powerful currents of the icy Piave for up to 16 hours; 50 died in the river during the campaign, a casualty rate of over 60%.

[citation needed] At dawn on the 31st, the Italian Fourth Army resumed the offensive on Monte Grappa and this time was able to advance beyond the old Austrian positions towards Feltre.

[36] Under the terms of the Austrian-Italian Armistice of Villa Giusti, Austria-Hungary's forces were required to evacuate not only all territory occupied since August 1914 but also South Tirol, Tarvisio, the Isonzo Valley, Gorizia, Trieste, Istria, western Carniola, and Dalmatia.

German chief-of-staff Erich Ludendorff, a prominent World War I figure, stressed the importance of the battle, claiming that its outcome prompted the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, "dragging Germany in its fall".

[4] In his memories Ludendorff wrote: "The Austro-Hungarian Army had completely dissolved as a result of the fighting in Upper Italy between the 24th October and the 4th November.

"[41] German historian Ernst Nolte contended that Vittorio Veneto was "an encounter which had merely given the coup de grace to the abandoned army of an already crumbling state.