Battle of Zacatecas (1914)

[1] On June 23, 1914, Pancho Villa's División del Norte (Division of the North) decisively defeated the federal troops of General Luis Medina Barrón defending the town of Zacatecas.

However, the Toma de Zacatecas also marked the end of support of Villa's Division of the North from Constitutionalist leader Venustiano Carranza and US President Woodrow Wilson.

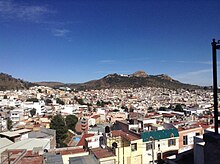

Zacatecas, a silver-mining town of 30,000 inhabitants, possessed a strategic military asset: a railroad junction that had to be captured in order to advance from the north on the capital, Mexico City.

[3] In contrast, Villa's División del Norte was comparatively well organized, employed trained federal defectors in key roles, and included effective artillery and mounted units.

Combined with his recent victories overshadowing other Constitutionalist generals, Carranza grew distrustful of Villa and saw him as a potential rival in the control over Mexico.

[12] On June 20, 1914, a federal relief detachment of about two thousand men reached Zacatecas although two further columns of reinforcements from the south were unable to bypass blocking Constitututionalist forces.

Villa led multiple cavalry charges against the stronghold on El Grillo, while Ángeles directed his twenty-nine field and mountain artillery pieces at both hills.

According to James Caldwell, the British consul stationed in Zacatecas, the morale of the troops, who had fought bravely until this point, suddenly collapsed and the streets became chaotic.

The greatest single act of destruction in the city occurred when a lieutenant colonel defending the federal headquarters blew up the ammunition stores to avoid surrender.

[18] The killing of prisoners continued until former federal officer General Felipe Ángeles arrived at dusk and ordered the executions to cease.

Villa's forces were accordingly unable to move south from Zacatecas and it was the Army Corps of the Northwest,[22][23] commanded by Álvaro Obregón, that led the advance on Mexico City.

The remaining federal commanders ordered the disbandment of the regular army and the rurales (mounted police) in August, following abortive efforts to negotiate a merger with revolutionary factions.

[26] Instead, the federal commanders entered into the Teoloyucan Treaties, in which they agreed to cease opposition to Obregón's forces and to assist them in protecting Mexico City from the approaching Zapatistas.