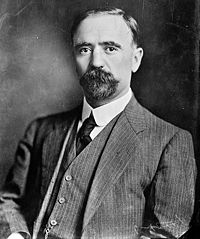

Venustiano Carranza

Born in Coahuila to a prominent landowning family, he served as a senator for his state during the Porfiriato, appointed by President and de facto dictator Porfirio Díaz.

Furthermore his government in this period was in a pre-constitutional, extralegal state, to which both his best generals, Álvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa, objected to Carranza's seizure of the national presidency.

The constitution that the revolutionaries drafted and ratified in 1917 now empowered the Mexican state to embark on significant land reform and recognized labor's rights, and curtail the power and influence of the Catholic Church.

Sonoran revolutionary generals Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta, who held significant power, rose up against Carranza under the Plan of Agua Prieta.

Carranza fled Mexico City, along with thousands of his supporters and with gold of the Mexican treasury, aiming to set up a rival government in Veracruz but he was assassinated in 1920.

[9] José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza was born in the town of Cuatro Ciénegas, in the state of Coahuila, in 1859, to a prosperous cattle-ranching family[10] of Basque descent.

Venustiano Carranza and his brother, who had now gained power and influence in the area,[17] were granted a personal audience with Reyes in order to explain the justification for the uprising and the ranchers' opposition to Garza Galán.

Madero favored having Díaz and Corral resign, with Francisco León de la Barra serving as interim president until a new election could be held.

Carranza was a seasoned politician, unlike Madero, and he argued that allowing Díaz and Corral to simply resign would legitimate their rule; an interim government would merely be a prolongation of the dictatorship and would discredit the Revolution.

He had built a state militia, funded by levying new taxes on enterprises, it could not withstand the well-armed, substantial force of the Federal Army controlled by General, now President, Huerta.

Carranza determined that it was safe to leave Sonora, and traveled to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, on the border with the United States, which served as his capital for the remainder of his struggle with Huerta.

Villa diverged from Carranza's opposition to the U.S. occupation of Veracruz, which occurred following the arrest of nine U.S. Navy sailors by Federal Army troops over a misunderstanding about fuel supplies.

He drew upon a network of well-placed Protestants in the effort[34] Cabrera became Carranza's Minister of Finance and drafted his agrarian law, which proved important for the recruitment of peasants to the Constitutionalists' cause.

[36] The protracted Mexican civil war waged to oust him in 1913-14 was a threat to U.S. investments in Mexico, since confiscating, imposing forced loans, or otherwise stripping resources from foreign enterprises was a key way to fund the revolutionaries' struggles.

His political program did not promise any kind of social or economic changes in Mexico seemed to be the best revolutionary leader to back in the struggle, bring it to an end, and restore some semblance of the old order, which had benefited U.S. investors and kept its southern border quiet.

On 8 July 1914, Villistas and Carrancistas had signed the Treaty of Torreón, in which they agreed that after Huerta's forces were defeated, 150 generals of the Revolution would meet to determine the political future of the country.

His ally Luis Cabrera then codified this into the agrarian law that Carranza issued in January 1915, creating communally held village lands now called ejidos.

[48] Historian Friedrich Katz has postulated that peasants flocked to Carranza because his well-publicized and widely distributed land law was a national policy, not one confined to Morelos (as with Zapata) or parts of the north (as with Villa), leading to the "first political mobilization outside their territories.

The plantations were not broken up in land reform, but the henequen was bought by a state-owned corporation, which took a portion of the profits for itself, helping to fund the Carranza movement's financial position.

[17] With the defeat of the División del Norte in the Battles of Celaya in April 1915 and the army of the Zapatistas, by mid-1915, Carranza was President of Mexico as head of what he termed a "Pre-constitutional Government".

When the Constitutional Convention met in December 1916, it contained only 85 conservatives and centrists close to Carranza's brand of liberalism, a group known as the bloque renovador ("renewal faction").

These radical delegates were particularly inspired by the thought of Andrés Molina Enríquez, in particular, his 1909 book Los Grandes Problemas Nacionales (English: "The Great National Problems").

Carranza also faced many armed, political enemies: Emiliano Zapata continued his rebellion in the mountains of Morelos; Félix Díaz, Porfirio Díaz's nephew, had returned to Mexico in May 1916 and organized an army that he called the Ejército Reorganizador Nacional (National Reorganizer Army), which remained active in Veracruz; the former Porfirians Guillermo Meixueiro and José María Dávila were active in Oaxaca, calling themselves Soberanistas (Sovereigntists) and insisting on local autonomy; General Manuel Peláez was in charge of La Huasteca; the brothers Saturnino Cedillo, Cleophas Cedillo, and Magdaleno Cedillo organized an opposition in San Luis Potosí; José Inés Chávez García led the resistance to Carranza's government in Michoacán; and Pancho Villa remained active in Chihuahua, although he had no significant forces.

[16] Carranza maintained a policy of formal neutrality during World War I, influenced by the anti-American sentiment that the United States' various interventions and invasions during the last century had caused.

[68][69] The assassination of Madero and José María Pino Suárez triggered a civil war that ended when the Constitutional Army defeated the forces of former ally Pancho Villa in the Battle of Celaya in April 1915.

[70][71] Nevertheless, Carranza was able to make the best out of a complicated situation; his government was officially recognized by Germany at the beginning of 1917, and by the United States on August 31, 1917, the latter as a direct consequence of the Zimmermann telegram as a measure to ensure Mexico's continued neutrality in the war.

[17] Obregón and allied Sonoran generals (including Plutarco Elías Calles and Adolfo de la Huerta), who were the strongest power bloc in Mexico, issued the Plan of Agua Prieta.

Rebels defeated the Federal Army at Ciudad Juárez, but rather than take the win and seize the presidency as Díaz had in 1876, Madero took deliberate steps to preserve much of the old order and have a civilian transition to power.

He pretends to be the genuine representative of the Great Masses of the People, and as we have seen, he not only tramples on each and every revolutionary principle, but harms with equal despotism, the most precious rights and the most respectable liberties of man and society.

General Lázaro Cárdenas, who was in the orbit of the Sonoran Dynasty and served as President of Mexico 1934–40, had designated his right-hand man, Manuel Ávila Camacho (derisively called "the unknown soldier" by his detractors) as his successor.