Bay of Pigs Invasion

Two days earlier, eight CIA-supplied B-26 bombers had attacked Cuban airfields and then returned to the U.S. On the night of 17 April, the main invasion force landed on the beach at Playa Girón in the Bay of Pigs, where it overwhelmed a local revolutionary militia.

The Cuban government's victory solidified Castro's role as a national hero and widened the political division between the two formerly allied countries, as well as emboldened other Latin American groups to undermine U.S. influence in the region.

Although he remained a moderating force and tried to prevent the mass reprisal killings of Batistanos advocated by many Cubans, Castro helped to set up trials of many figures involved in the old regime across the country, resulting in hundreds of executions.

[57] An early plan to thwart Castro was devised on 11 February 1960 by Tracy Barnes, Jake Esterline, Al Cox, Dave Phillips, and Jim Flannery to sabotage both Cuban and American Sugar mills.

[59] Bissell placed Droller in charge of liaising with anti-Castro segments of the Cuban American community living in the United States, and asked Hunt to fashion a government in exile, which the CIA would effectively control.

He furthermore asserted that international communism was using Cuba as an "operational base" for spreading revolution in the western hemisphere, and called on other OAS members to condemn the Cuban government for its breach of human rights.

[94] To Nixon's chagrin, the Kennedy campaign released a scathing statement on the Eisenhower administration's Cuba policy on 20 October 1960 which said that "we must attempt to strengthen the non-Batista democratic anti-Castro forces [...] who offer eventual hope of overthrowing Castro", claiming that "Thus far these fighters for freedom have had virtually no support from our Government.

Under Dulles and Bissell's insistence of the increasingly urgent need to do something with the troops being trained in Guatemala, Kennedy eventually agreed, although to avoid the appearance of American involvement, he requested the operation be moved from the city of Trinidad, Cuba to a less conspicuous location.

On 28 January 1961, Kennedy was briefed, together with all the major departments, on the latest plan (code-named Operation Pluto), which involved 1,000 men landed in a ship-borne invasion at Trinidad, Cuba, about 270 km (170 mi) south-east of Havana, at the foothills of the Escambray Mountains in Sancti Spiritus province.

[109] The invasion landing area was changed to beaches bordering the Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) in Las Villas Province, 150 km southeast of Havana, and east of the Zapata Peninsula.

[1][page needed][147] The Cuban security apparatus knew the invasion was coming, in part due to indiscreet talk by members of the brigade, some of which was heard in Miami and repeated in U.S. and foreign newspaper reports.

[155] After on-loading the attack planes in Norfolk Naval Base and taking on prodigious quantities of food and supplies sufficient for the seven weeks at-sea to come, the crew knew from the hasty camouflage of the ship and aircraft identifying numbers that a secret mission was on hand.

En route, Essex had made a night time stop at a Navy arms depot in Charleston, South Carolina, to load tactical nuclear weapons to be held ready during the cruise.

At a safe distance north of Cuba, the pilot feathered the engine with the pre-installed bullet holes in the cowling, radioed a mayday call, and requested immediate permission to land at Miami International airport.

[164] At 10:30 on 15 April at the United Nations (UN), Cuban Foreign Minister Raúl Roa accused the U.S. of aggressive air attacks against Cuba and that afternoon formally tabled a motion to the Political (First) Committee of the UN General Assembly.

[165] On 15 April, the Cuban national police, led by Efigenio Ameijeiras, started the process of arresting thousands of suspected anti-revolutionary individuals and detaining them in provisional locations such as the Karl Marx Theatre, the moat of La Cabaña and the Principe Castle, all in Havana, and the baseball park in Matanzas.

[113][page needed] The fleet, labeled the 'Cuban Expeditionary Force' (CEF), included five 2,400-ton (empty weight) freighter ships chartered by the CIA from the Garcia Line, and subsequently outfitted with anti-aircraft guns.

At Point Zulu, the seven CEF ships sailed north without the USN escorts, except for San Marcos that continued until the seven landing craft were unloaded when just outside the 5 kilometres (3 mi) Cuban territorial limit.

A flotilla containing equipment that broadcast sounds and other effects of a shipborne invasion landing provided the source of Cuban reports that briefly lured Fidel Castro away from the Bay of Pigs battlefront area.

[180] At about 11:00, Castro issued a statement over Cuba's nationwide network saying that the invaders, members of the exiled Cuban revolutionary front, have come to destroy the revolution and take away the dignity and rights of men.

By dusk, other Cuban ground forces gradually advanced southward from Covadonga, southwest from Yaguaramas toward San Blas, and westward along coastal tracks from Cienfuegos towards Girón all without heavy weapons or armour.

His fellow conspirators Rogelio González Corzo (alias "Francisco Gutierrez"), Rafael Diaz Hanscom, Eufemio Fernandez, Arturo Hernandez Tellaheche and Manuel Lorenzo Puig Miyar were also executed.

[208] On 21 December 1962, Castro and James B. Donovan, a U.S. lawyer aided by Milan C. Miskovsky, a CIA legal officer,[209] signed an agreement to exchange 1,113 prisoners for US$53 million in food and medicine, sourced from private donations and from companies expecting tax concessions.

Regarding the defections of some prominent figures within the Cuban government, Guevara remarked that this was because "the socialist revolution left the opportunists, the ambitious, and the fearful far behind and now advances toward a new regime free of this class of vermin.

Memorandum 55 stated that it was the Joint Chiefs of Staff who had the "responsibility for the defense of the nation in the Cold War" and memorandum 57 restricted the CIA's paramilitary operations by stating "Any large paramilitary operation wholly or partly covert which requires significant numbers of militarily trained personnel, amounts of military equipment which exceed normal CIA-controlled stocks and/or military experience of a kind and level peculiar to the Armed Services is properly the primary responsibility of the Department of Defense with the CIA in a supporting role".

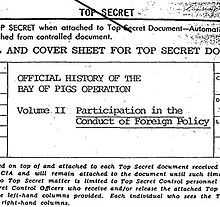

Jack Pfeiffer, who worked as a historian for the CIA until the mid-1980s, simplified his own view of the failed Bay of Pigs effort by quoting a statement which Raúl Castro, Fidel's brother, had made to a Mexican journalist in 1975: "Kennedy vacillated.

[134][page needed] Further study shows that among various components of groupthink analyzed by Irving Janis, the Bay of Pigs Invasion followed the structural characteristics that led to irrational decision making in foreign policy pushed by deficiency in impartial leadership.

[239] An account of the process of invasion planning reads,[240] At each meeting, instead of opening up the agenda to permit a full airing of the opposing considerations, [President Kennedy] allowed the CIA representatives to dominate the entire discussion.

A considerable amount of information presented before President Kennedy proved to be false in reality, such as the support of the Cuban people for Fidel Castro, making it difficult to assess the actual situation and the future of the operation.

[247] A Cuban FAR combatant at the Bay of Pigs, José Ramón Fernández, attended the conference, as did four members of Brigade 2506, Roberto Carballo, Mario Cabello, Alfredo Duran, and Luis Tornes.