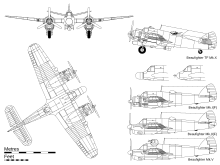

Bristol Beaufighter

The Beaufighter proved to be an effective night fighter, which came into service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Battle of Britain, its large size allowing it to carry heavy armament and early aircraft interception radar without major performance penalties.

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) also made extensive use of the type as an anti-shipping aircraft, such as during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

During the Munich Crisis, the Bristol Aeroplane Company recognised that the Royal Air Force (RAF) had an urgent need for a long-range fighter aircraft capable of carrying heavy payloads for maximum destruction.

[1] The Air Ministry produced draft Specification F.11/37 in response to Bristol's suggestion for an "interim" aircraft, pending the proper introduction of the Whirlwind.

This conversion served to speed progress; Bristol had promised series production in early 1940 on the basis of an order being placed in February 1939.

Two weeks prior to the prototype's first flight, an initial production contract for 300 aircraft under Specification F.11/37 was issued by the Air Ministry, ordering the type "off the drawing board".

[6] During the pre-delivery trials, the first prototype R2052, powered by a pair of two-speed supercharged Hercules I-IS engines, had achieved 335 mph (539 km/h) at 16,800 ft (5,120 m) in a clean configuration.

According to aviation author Philip Moyes, the performance of the second prototype was considered disappointing, particularly as the Hercules III engines of the initial production aircraft would likely provide little improvement, especially in light of additional operational equipment being installed; it was recognised that demand for the Hercules engine to power other aircraft such as the Short Stirling bomber posed a potential risk to the production rate of the Beaufighter.

[7] Due to production of the Griffon being reserved for the Fairey Firefly, the Air Ministry instead opted for the Rolls-Royce Merlin to power the Beaufighter until the manufacturing rate of the Hercules could be raised by a new shadow factory in Accrington.

[7] The armament of the Beaufighter had also undergone substantial changes, the initial 60-round capacity spring-loaded drum magazine arrangement being awkward and inconvenient; alternative systems were investigated by Bristol.

The initial rejection was later reversed, upon the introduction of a new electrically driven feed derived from Châtellerault designs brought to Britain by Free French officers, which was quite similar to Bristol's original proposal.

[13] Large orders for the Beaufighter were placed around the outbreak of the Second World War, including one for 918 aircraft shortly after the arrival of the initial production examples.

[7] For the maximum rate of production, sub-contracting of the major components was used wherever possible and two large shadow factories to perform final assembly work on the Beaufighter were established via the Ministry of Aircraft Production; the first, operated by the Fairey Aviation Company, was at Stockport, Greater Manchester and the second shadow, run by Bristol, was at Weston-super-Mare, Somerset.

[19] The aircraft employed an all-metal monocoque construction, comprising three sections with extensive use of 'Z-section' frames and 'L-section' longeron.

[19] The extra power had presented vibration issues during development; in the final design, the engines were mounted on longer and more flexible struts, which extended from the front of the wings.

The majority of the fuselage was positioned aft of the wing and, with the engine cowlings and propellers now further forward than the tip of the nose, gave the Beaufighter a characteristically stubby appearance.

In an emergency, the pilot could operate a lever that remotely released the hatch, grasp two steel overhead tubes and lift himself out of his seat, swing his legs over the open hatchway, then let go to drop through.

[23][24] When Beaufighters were developed as fighter-torpedo bombers, they used their firepower (often the machine guns were removed) to suppress flak fire and hit enemy ships, especially escorts and small vessels.

Mass production of the type had coincidentally occurred at almost exactly the same time as the first British aircraft interception radar sets were becoming available; the two technologies quickly became a natural match in the night fighter role.

[1] As the faster de Havilland Mosquito took over as the main night fighter in mid-to-late 1942, the heavier Beaufighter made valuable contributions in other areas such as anti-shipping, ground attack and long-range interdiction, in every major theatre of operations.

As some models of the twin-engined Beaufighter could not stay aloft on one engine unless the dead propeller was feathered, this deficiency contributed to several operational losses and the deaths of aircrew.

[30] In the Mediterranean, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) 414th, 415th, 416th and 417th night fighter squadrons received a hundred Beaufighters in the summer of 1943, achieving their first victory in July 1943.

Although the Northrop P-61 Black Widow fighter began to arrive in December 1944, USAAF Beaufighters continued to fly night operations in Italy and France until late in the war.

[32] In December 1941, Beaufighters participated in Operation Archery, providing suppressing fire while British Commandos landed on the occupied Norwegian island of Vågsøy.

The Hercules Mk.XVII, developing 1,735 hp (1,294 kW) at 500 ft (150 m), was installed in the Mk.VIC airframe to produce the TF Mk.X (torpedo fighter), commonly known as the "Torbeau".

The most famous of these was the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, during which Beaufighters were used in a fire-suppression role in a mixed force with USAAF Douglas A-20 Boston and North American B-25 Mitchell bombers.

The Japanese convoy, under the impression that they were under torpedo attack from Beauforts, made the tactical error of turning their ships towards the Beaufighters, which allowed the Beaufighters to inflict severe damage on the ships' anti-aircraft guns, bridges and crews during strafing runs with their four 20 mm nose cannons and six wing-mounted .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns.

[19][25] The role of the Beaufighters during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea was recorded by war correspondent and film-maker Damien Parer, who had flown during the engagement standing behind the pilot of one of the No.

[19][25] On 2 November 1943, another high-profile event involving the type occurred when a Beaufighter, A19-54, won the second of two unofficial races against an A-20 Boston bomber.

The aircraft ditched in March 1943, after an engine failure occurred soon after take-off and lies inverted on the sea bed, in 38 metres (125 ft) of water.