Beaune Altarpiece

The large central panel spans both registers and shows Christ seated on a rainbow in judgement, while below him, the Archangel Michael holds scales to weigh souls.

The two painted sides of the outer panels have been separated to be displayed; traditionally, the shutters would have been opened only on selected Sundays or church holidays.

[5] Furthermore, in 1435, when the Treaty of Arras failed to bring a cessation to the longstanding hostility and animosity between Burgundy and France, Beaune suffered first the ravages of marauding bands of écorcheurs, who roamed the countryside scavenging in the late 1430s and early 1440s, then an ensuing famine.

[13] St Michael developed a cult following in 15th-century France, and he was seen as a guardian of the dead, a crucial role given the prevalence of plague in the region.

According to the art historian Barbara Lane, patients were unlikely to survive their stay at Beaune, yet the representation of St Michael offered consolation as they could "gaze on his figure immediately above the altar of the chapel every time the altarpiece was opened.

[26] The celestial sphere, towards which the saved move, is dramatically presented with a "radiant gold background, spanning almost the entire width of the altarpiece".

His palms are open, revealing the wounds sustained when they were nailed to the cross, while his cope gapes in places making visible the injury caused by the lance, from which pours deep-red blood.

Michael is given unusual prominence in a "Last Judgement" for the period, and his powerful presence emphasises the work's function in a hospice and its preoccupation with the liturgy of death.

His feet are positioned as if he is stepping forward, about to move out of the canvas, and he looks directly at the observer, giving the illusion of judging not only the souls in the painting but also the viewer.

[27] Michael, like Sebastian and Anthony, was a plague saint and his image would have been visible to patients through the openings of the pierced screen as they lay in their beds.

[34] He is portrayed with iconographic elements associated with the Last Judgement,[20] and, dressed in a red cope with woven golden fabrics over a shining white alb, is by far the most colourful figure in the lower panels, "hypnotically attracting the viewer's glance" according to Lane.

The saved walk towards the gates of Heaven where they are greeted by a saint; the damned arrive at the mouth of Hell and fall en masse into damnation.

[39] This contrasts with another couple on the opposite panel who face Hell; the woman is hunched over as the man raises his hand in vain to beseech God for mercy.

[44] Van der Weyden depicts Hell as a gloomy, crowded place of both close and distant fires, and steep rock faces.

[45] Erwin Panofsky was the first to mention this absence, and proposed that van der Weyden had opted to convey torment in an inward manner, rather than through elaborate descriptions of devils and fiends.

He wrote, "The fate of each human being ... inevitably follows from his own past, and the absence of any outside instigator of evil makes us realize that the chief torture of the Damned is not so much physical pain as a perpetual and intolerably sharpened consciousness of their state".

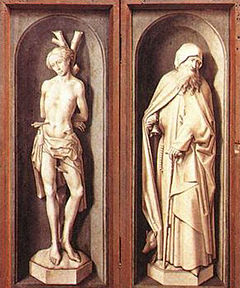

[49] The two small upper register panels show a conventional Annunciation scene, with the usual dove representing the Holy Spirit.

Gabriel's scroll and Mary's lily appear to be made of stone; the figures cast shadows against the back of their niches, creating a sense of depth which adds to the illusion.

[19] Rolin and de Salins can be identified by the coats-of-arms held by the angels;[1] husband and wife kneel at cloth-covered prie-dieux (portable altars) displaying their emblems.

Although De Salins was reputedly pious and charitable, and even perhaps the impetus for the building of the hospice, she is placed on the exterior right,[19] traditionally thought of as an inferior position corresponding to Hell, linking her to Eve, original sin and the Fall of man.

In van Eyck's portrait, Rolin is presented as perhaps pompous and arrogant; here – ten years later – he appears more thoughtful and concerned with humility.

[50][51] Campbell notes wryly that van der Weyden may have been able to disguise the sitter's ugliness and age, and that the unusual shape of his mouth may have been downplayed.

Beneath the lily, in white paint[36] are the words of Christ: VENITE BENEDICTI PATRIS MEI POSSIDETE PARATUM VOBIS REGNUM A CONSTITUTIONE MUNDI ("Come ye blessed of my father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundations of the world").

The text beneath the sword reads: DISCEDITE A ME MALEDICTI IN IGNEM ÆTERNUM QUI PARATUS EST DIABOLO ET ANGELIS EJUS ("Depart from me ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels").

When it was brought out, the nude souls – thought to be offensive – were painted over with clothing and flames; it was moved to a different room, hung three metres (10 ft) from the ground, and portions were whitewashed.

[55] Since before 1000, complex depictions of the Last Judgement had been developing as a subject in art, and from the 11th century became common as wall-painting in churches, typically placed over the main door in the west wall, where it would be seen by worshippers as they left the building.

Since this scene has no biblical basis, it is often thought to draw from pre-Christian parallels such as depictions of Anubis performing a similar role in Ancient Egyptian art.

[59] Van der Weyden may have drawn influence from Stefan Lochner's c. 1435 Last Judgement, and a similar c. 1420 painting now in the Hotel de Ville, Diest, Belgium.

Points of reference include Christ raised over a Great Deësis of saints, apostles and clergy above depictions of the entrance to Heaven, and the gates of Hell.

[60] The work's moralising tone is apparent from some of its more overtly dark iconography, its choice of saints, and how the scales tilt far lower beneath the weight of the damned than the saved.