Crucifixion Diptych (van der Weyden)

Scholars have theorized that they could be the left and center panels of a triptych, that they formed either the wings or shutters of an altarpiece, or that they were intended to decorate an organ case.

Art historian E. P. Richardson proposed that they were the center panel of the lost Cambrai altarpiece (executed between 1455 and 1459), a single painting now split into two parts.

[7] Carthusians lived a severely ascetic existence: absolute silence, isolation in one's cell except for daily Mass and Vespers, a communal meal only on Sundays and festival days, bread and water on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, clothes and bedding of the coarsest materials.

[11] Art historian Dirk de Vos describes the diptych as a "monastically inspired devotional painting" whose composition was "largely determined by the ascetic worship of the Carthusians and Dominicans.

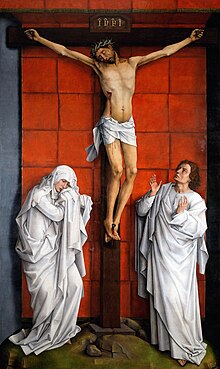

Both are dressed in pale folded robes, and again presented before a draped red cloth of honor (which, given the creases, appears to have been recently unfolded).

The diptych was executed late in the artist's life, and is unique among paintings of the early Northern Renaissance in its utilization of a flat unnaturalistic background to stage figures which are yet, typically highly detailed.

[15] Nonetheless, the contrast of vivid primary reds and whites serves to achieve an emotional effect typical of van der Weyden's best work.

[20] In Vita Christi (1374) the Carthusian theologian Ludolph of Saxony introduced the concept of immersing and projecting oneself into a Biblical scene from the life of Christ.

"[22] If the Philadelphia diptych was utilized as a Ludolphian devotional painting (as the Escorial Crucifixion certainly was), a monk could have empathized with the suffering of Christ and the Virgin, but also been able to project himself into the scene as the ever-loyal (and ever-chaste) St. John.

With this intended function, van der Weyden's decision to strip away the extraneous detail present in his other Crucifixions can be seen as having had both an artistic and a practical purpose.

Near the upper edge of a panel Rosen found gold paint, one of the factors that led him to conclude that the blue-black sky was an 18th-century addition.

Van der Weyden's broad massing of color in the blue-black sky was something new in Northern Renaissance art, although common in Italian frescoes.