Behar

[4] In the first reading, on Mount Sinai, God told Moses to tell the Israelites the law of the Sabbatical year for the land.

[9] In the second reading, in selling or buying property, the people were to charge only for the remaining number of crop years until the jubilee, when the land would be returned to its ancestral holder.

[13] If one had no one to redeem, but prospered and acquired enough wealth, he could refund the pro rata share of the sales price for the remaining years until the jubilee, and return to his holding.

[15] But houses in villages without encircling walls were treated as open country subject to redemption and release through the jubilee.

[20] In the sixth reading, if the kinsman continued in straits and had to give himself over to a creditor for debt, the creditor was not to subject him to the treatment of a slave, but to treat him as a hired or bound laborer until the jubilee year, at which time he was to be freed to go back to his family and ancestral holding.

[27] The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[28] Leviticus 25:8–10 refers to the Festival of Yom Kippur.

In Isaiah 57:14–58:14, the Haftarah for Yom Kippur morning, God describes "the fast that I have chosen [on] the day for a man to afflict his soul."

But Isaiah 58:6–10 goes on to impress that "to afflict the soul," God also seeks acts of social justice: "to loose the fetters of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke," "to let the oppressed go free," "to give your bread to the hungry, and .

But before these commandments were issued, in Genesis 28:18, Jacob took the stone on which he had slept, set it up as a pillar (מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah), and poured oil on the top of it.

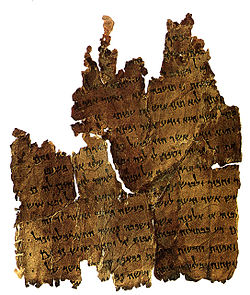

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[35] The Damascus Document of the Qumran sectarians prohibited non-cash transactions with Jews who were not members of the sect.

Professor Lawrence Schiffman of New York University read this regulation as an attempt to avoid violating prohibitions on charging interest to one's fellow Jew in Exodus 22:25; Leviticus 25:36–37; and Deuteronomy 23:19–20.

Apparently, the Qumran sect viewed prevailing methods of conducting business through credit to violate those laws.

[39] The Mishnah taught that one could plow a grain-field in the sixth year until the moisture had dried up in the soil (that it, after Passover, when rains in the Land of Israel cease) or as long as people still plowed in order to plant cucumbers and gourds (which need a great deal of moisture).

[44] The Mishnah taught that the fines for rape, seduction, the husband who falsely accused his bride of not having been a virgin (as in Deuteronomy 22:19), and any judicial court matter are not canceled by the Sabbatical year.

[45] The Mishnah told that when Hillel the Elder observed that the nation withheld from lending to each other and were transgressing Deuteronomy 15:9, "Beware lest there be in your mind a base thought," he instituted the prozbul, a court exemption from the Sabbatical year cancellation of a loan.

[46] The Mishnah recounted that a prozbul would provide: "I turn over to you, so-and-so, judges of such and such a place, that any debt that I may have outstanding, I shall collect it whenever I desire."

Chananya ben Chachinai said that the plower also may have been wearing a garment of wool and linen (in violation of Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11).

One had committed an indecent act, while the other had eaten unripe figs of the seventh year in violation of Leviticus 25:6.

[49] The latter parts of tractate Arakhin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the jubilee year in Leviticus 25:8–34.

[50] The Mishnah taught that the jubilee year had the same ritual as Rosh Hashanah for blowing the shofar and for blessings.

[51] The Mishnah taught that exile resulted from (among other things) transgressing the commandment (in Leviticus 25:3–5 and Exodus 23:10–11) to observe a Sabbatical year for the land.

[56] The Mishnah taught that the law of fraud applied to both the buyer and the seller, both the ordinary person and the merchant.

The Baraita cited as examples of verbal wrongs: (1) reminding penitents of their former deeds, (2) reminding converts' children of their ancestors' deeds, (3) questioning the propriety of converts' coming to study Torah, (4) speaking to those visited by suffering as Job's companions spoke to him in Job 4:6–7, and (5) directing donkey drivers seeking grain to a person whom one knows has never sold grain.

And a Tanna taught before Rav Naḥman bar Isaac that one who publicly makes a neighbor blanch from shame is as one who sheds blood.

Reading Exodus 22:20, "And you shall not mistreat a convert nor oppress him, because you were strangers in the land of Egypt," a Baraita reported that Rabbi Nathan taught that one should not mention in another a defect that one has oneself.

[66] Similarly, Rav Naḥman taught that Leviticus 25:25 exhorts Israel to acts of charity, because fortune revolves like a wheel in the world, sometimes leaving one poor and sometimes well off.

"[69] The Sifra read the words of Leviticus 25:35, "You shall support him," to teach that one should not let one's brother who grows poor to fall down.

The Gemara asked where Scripture formally prohibited abduction (as Deuteronomy 22:7 and Exodus 21:16 state only the punishment).

[80] The parashah is discussed in these modern sources: In 1877, August Klostermann observed the singularity of Leviticus 17–26 as a collection of laws and designated it the "Holiness Code.

"[81] William Dever noted that Leviticus 25:29–34 recognizes three land-use distinctions: (1) walled cities (עִיר חוֹמָה, ir chomot); (2) unwalled villages (חֲצֵרִים, chazeirim, specially said to be unwalled); and (3) land surrounding such a city (שְׂדֵה מִגְרַשׁ, sedeih migrash) and the countryside (שְׂדֵה הָאָרֶץ, sedeih ha-aretz, "fields of the land").