Bel canto

In spite of the repeated reactions against bel canto (or its abuses, such as display for its own sake; Gluck, Wagner) and the frequent exaggeration of its virtuoso element (coloratura), it must be considered as a highly artistic technique and the only proper one for Italian opera and for Mozart.

[10] The phrase "bel canto" was not commonly used until the latter part of the 19th century, when it was set in opposition to the development of a weightier, more powerful style of speech-inflected singing associated with German opera and, above all, Richard Wagner's revolutionary music dramas.

[citation needed] They subjected the mechanics of their voice production to greater pressures and cultivated the exciting upper part of their respective ranges at the expense of their mellow but less penetrant lower notes.

[citation needed] Initially at least, the singing techniques of 19th-century contraltos and basses were less affected by the musical innovations of Verdi, which were built upon by his successors Amilcare Ponchielli (1834–1886), Arrigo Boito (1842–1918) and Alfredo Catalani (1854–1893).

One reason for the eclipse of the old Italian singing model was the growing influence within the music world of bel canto's detractors, who considered it to be outmoded and condemned it as vocalization devoid of content.

Cotogni and his followers invoked it against an unprecedentedly vehement and vibrato-laden style of vocalism that singers increasingly used after around 1890 to meet the impassioned demands of verismo writing by composers such as Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924), Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857–1919), Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945), Francesco Cilea (1866–1950) and Umberto Giordano (1867–1948), as well as the auditory challenges posed by the non-Italianate stage works of Richard Strauss (1864–1949) and other late-romantic/early-modern era composers, with their strenuous and angular vocal lines and frequently dense orchestral textures.

To complicate matters further, German musicology in the early 20th century invented its own historical application for bel canto, using the term to denote the simple lyricism that came to the fore in Venetian opera and the Roman cantata during the 1630s and '40s (the era of composers Antonio Cesti, Giacomo Carissimi and Luigi Rossi) as a reaction against the earlier, text-dominated stile rappresentativo.

[1] This anachronistic use of the term bel canto was given wide circulation in Robert Haas's Die Musik des Barocks[13] and, later, in Manfred Bukofzer's Music in the Baroque Era.

That situation changed significantly after World War II with the advent of a group of enterprising orchestral conductors and the emergence of a fresh generation of singers such as Montserrat Caballé, Maria Callas, Leyla Gencer, Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills and Marilyn Horne, who had acquired bel canto techniques.

Many 18th-century operas that require adroit bel canto skills have also experienced post-war revivals, ranging from lesser-known Mozart and Haydn to extensive Baroque works by Handel, Vivaldi and others.

Today's pervasive idea that singers should refrain from improvising and always adhere strictly to the letter of a composer's published score is a comparatively recent phenomenon, promulgated during the first decades of the 20th century by dictatorial conductors such as Arturo Toscanini (1867–1957), who championed the dramatic operas of Verdi and Wagner and believed in keeping performers on a tight interpretive leash.

They strove to strengthen the respiratory muscles of their pupils and equip them with such time-honoured vocal attributes as "purity of tone, perfection of legato, phrasing informed by eloquent portamento, and exquisitely turned ornaments", as noted in the introduction to Volume 2 of Scott's The Record of Singing.

Major refinements occurred to the existing system of voice classification during the 19th century as the international operatic repertoire diversified, split into distinctive nationalist schools and expanded in size.

Fundamentally, though, they all subscribed to the same set of bel canto precepts, and the exercises that they devised to enhance breath support, dexterity, range, and technical control remain valuable and, indeed, some teachers still use them.

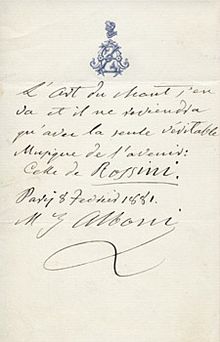

[1] Manuel García (1805–1906), author of the influential treatise L'Art du chant, was the most prominent of the group of pedagogues that perpetuated bel-canto principles in teachings and writings during the second half of the 19th century.