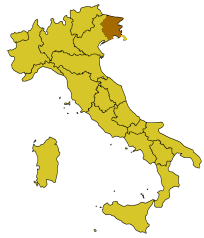

Benandanti

According to Early Modern records, benandanti were believed to have been born with a caul on their head, which gave them the ability to take part in nocturnal visionary traditions that occurred on specific Thursdays during the year.

In 1575, the benandanti first came to the attention of the Friulian Church authorities when a village priest, Don Bartolomeo Sgabarizza, began investigating the claims made by the benandante Paolo Gasparotto.

Although Sgabarizza soon abandoned his investigations, in 1580 the case was reopened by the inquisitor Fra' Felice de Montefalco, who interrogated not only Gasparotto but also a variety of other local benandanti and spirit mediums, ultimately condemning some of them for the crime of heresy.

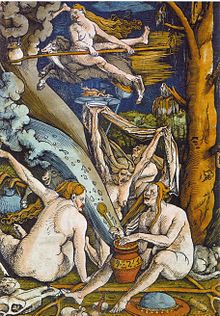

Under pressure by the Inquisition, these nocturnal spirit travels (which often included sleep paralysis) were assimilated to the diabolised stereotype of the witches' Sabbath, leading to the extinction of the benandanti cult.

The first historian to study the benandanti tradition was the Italian Carlo Ginzburg, who began an examination of the surviving trial records from the period in the early 1960s, culminating in the publication of his book The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1966, English translation 1983).

He furthermore argued that it was only one surviving part of a much wider European tradition of visionary experiences that had its origins in the pre-Christian period, identifying similarities with Livonian werewolf beliefs.

[3][4] In the folklore of Friuli at the time, cauls were imbued with magical properties, being associated with the ability to protect soldiers from harm, to cause an enemy to withdraw, and to help lawyers win their legal cases.

[6] For this reason, historian Norman Cohn asserted that the benandanti tradition highlights how "not only the waking thoughts but the trance experiences of individuals can be deeply conditioned by the generally accepted beliefs of the society in which they live".

When they left their bodies they traveled to a great feast, where they danced, ate and drank with a procession of spirits, animals and faeries, and learned who amongst the villagers would die in the next year.

The earliest accounts of the benandanti's journeys, dating from 1575, did not contain any of the elements then associated with the diabolic witches' sabbath; there was no worshipping of the Devil (a figure who was not even present), no renunciation of Christianity, no trampling of crucifixes and no defilement of sacraments.

[11] In early 1575, Paolo Gasparotto, a male benandante who lived in the village of Iassico (modern spelling: Giassìcco), gave a charm to a miller from Brazzano named Pietro Rotaro, in the hope of healing his son, who had fallen sick from some unknown illness.

"[12] Sometimes they go out to one country region and sometimes to another, perhaps to Gradisca or even as far away as Verona, and they appear together jousting and playing games; and ... the men and women who are the evil-doers carry and use the sorghum stalks which grow in the fields, and the men and women who are benandanti use fennel stalks; and they go now one day and now another, but always on Thursdays, and ... when they make their great displays they go to the biggest farms, and they have days fixed for this; and when the warlocks and witches set out it is to do evil, and they must be pursued by the benandanti to thwart them, and also to stop them entering the houses, because if they do not find clear water in the pails they go into the cellars and spoil the wine with certain things, throwing filth in the bungholes.Don Sgabarizza was concerned with such talk of witchcraft, and on 21 March 1575, he appeared as a witness before both the vicar general, Monsignor Jacopo Maracco, and the Inquisitor Fra Giulio d'Assis, a member of the Order of the Minor Conventuals, at the monastery of San Francesco of Cividale del Friuli, in the hope that they could offer him guidance in how to proceed in this situation.

In response to the priest's disbelief, Gasparotto invited both him and the Inquisitor to join the benandanti on their next journey, although refused to provide the names of any other members of the "fraternity", stating that he would be "badly beaten by the witches" should he do so.

[16] During and after the meal, Sgabarizza once more discussed the journeys of the benandanti with both Gasparotto and the miller Pietro Rotaro, and later learned of another self-professed benandante, the public crier Battista Moduco of Cividale, who offered more information on what occurred during their nocturnal visions.

For Montefalco, the introduction of this element led him to suspect that the actions of Gasparotto were themselves heretical and satanic, and his method of interrogation became openly suggestive, putting forward the idea that the angel was actually a demon in disguise.

Initially denying that she had such an ability to the inquisitor, she eventually relented and told him of how she believed that she could see the dead, and how she sold their messages to members of the local community willing to pay, using the money in order to alleviate the poverty of her family.

Known among locals as Donna Aquilina, she was said to have become relatively rich through offering her services as a professional healer, but when she learned that she was under suspicion from the Holy Inquisition, she fled the city, and Montefalco did not initially set out to locate her.

[27] On 1 October 1587, a priest known as Don Vincenzo Amorosi of Cesana denounced a midwife named Caterina Domenatta to the inquisitor of Aquileia and Concordia, Fra Giambattista da Perugia.

[28] In 1600, a woman named Maddalena Busetto of Valvasone made two depositions regarding the benandanti of Moruzzo village to Fra Francesco Cummo of Vicenza, the commissioner of the Inquisition in the dioceses of Aquileia and Concordia.

[35] The members of the Holy Office did not believe that the stories she related ever took place, allowing the two accused witches to go free, and condemning Panzona to a three-year prison sentence for heresy.

[37] In February 1622 the inquisitor of Aquileia, Fra Domenico Vico of Osimo was informed that a beggar and benandante named Lunardo Badou had been accusing various individuals of being witches in the area of Gagliano, Cividale del Friuli, and Rualis.

[41] During the 1960s, the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg was searching through the Archepiscopal Archives of Udine when he came across the 16th and 17th century trial records which documented the interrogation of several benandanti and other folk magicians.

In Europe's Inner Demons (1975), English historian Norman Cohn asserted that there was "nothing whatsoever" in the source material to justify the idea that the benandanti were the "survival of an age-old fertility cult".

[44] The German anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr briefly discussed the benandanti in his book Dreamtime: Concerning the Boundary between Wilderness and Civilization (1978, English translation 1985).

[44] Echoing these views in 1999 was English historian Ronald Hutton, who stated that Ginzburg's claim that the benandanti's visionary traditions were a survival from pre-Christian practices was an idea resting on "imperfect material and conceptual foundations".

He thought that this approach was a "striking late application" of "the ritual theory of myth", a discredited anthropological idea associated particularly with Jane Ellen Harrison's 'Cambridge group' and Sir James Frazer.

[55] The themes associated with the benandanti (leaving the body in spirit, possibly in the form of an animal; fighting for the fertility of the land; banqueting with a queen or goddess; drinking from and soiling wine casks in cellars) are found repeatedly in other testimonies: from the armiers of the Pyrenees, from the followers of Signora Oriente in 14th century Milan and the followers of Richella and "the wise Sibillia" in 15th century Northern Italy, and much further afield, from Livonian werewolves, Dalmatian kresniki, Serbian zduhaćs, Hungarian táltos, Romanian căluşari and Ossetian burkudzauta.

[46] Historian Carlo Ginzburg posits a relationship between the benandanti cult and the shamanism of the Baltic and Slavic cultures, a result of diffusion from a central Eurasian origin, possibly 6,000 years ago.