Ben Jonson

By 1597, he was a working playwright employed by Philip Henslowe, the leading producer for the English public theatre; by the next year, the production of Every Man in His Humour (1598) had established Jonson's reputation as a dramatist.

A year later, Jonson was again briefly imprisoned, this time in Newgate Prison, for killing Gabriel Spenser in a duel on 22 September 1598 in Hogsden Fields[12] (today part of Hoxton).

Tried on a charge of manslaughter, Jonson pleaded guilty but was released by benefit of clergy,[1] a legal ploy through which he gained leniency by reciting a brief Bible verse (the neck-verse), forfeiting his "goods and chattels" and being branded with the so-called Tyburn T on his left thumb.

Shortly after his release from a brief spell of imprisonment imposed to mark the authorities' displeasure at the work, in the second week of October 1605, he was present at a supper party attended by most of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators.

[22] On his arrival he lodged initially with John Stuart, a cousin of King James, in Leith, and was made an honorary burgess of Edinburgh at a dinner laid on by the city on 26 September.

[22] He stayed in Scotland until late January 1619, and the best-remembered hospitality he enjoyed was that of the Scottish poet, William Drummond of Hawthornden,[1] sited on the River Esk.

Jonson recounted that his father had been a prosperous Protestant landowner until the reign of "Bloody Mary" and had suffered imprisonment and the forfeiture of his wealth during that monarch's attempt to restore England to Catholicism.

Jonson's biographer Ian Donaldson is among those who suggest that the conversion was instigated by Father Thomas Wright, a Jesuit priest who had resigned from the order over his acceptance of Queen Elizabeth's right to rule in England.

[26] Alternatively, he could have been looking to personal advantage from accepting conversion since Father Wright's protector, the Earl of Essex, was among those who might hope to rise to influence after the succession of a new monarch.

[29] Jonson's conversion came at a weighty time in affairs of state; the royal succession, from the childless Elizabeth, had not been settled and Essex's Catholic allies were hopeful that a sympathetic ruler might attain the throne.

[7] In January 1606 he (with Anne, his wife) appeared before the Consistory Court in London to answer a charge of recusancy, with Jonson alone additionally accused of allowing his fame as a Catholic to "seduce" citizens to the cause.

[30] This was a serious matter (the Gunpowder Plot was still fresh in people's minds) but he explained that his failure to take communion was only because he had not found sound theological endorsement for the practice, and by paying a fine of thirteen shillings (156 pence) he escaped the more serious penalties at the authorities' disposal.

His habit was to slip outside during the sacrament, a common routine at the time—indeed it was one followed by the royal consort, Queen Anne of Denmark, herself—to show political loyalty while not offending the conscience.

[31] Leading church figures, including John Overall, Dean of St Paul's, were tasked with winning Jonson back to Protestantism, but these overtures were resisted.

For his part, Charles displayed a certain degree of care for the great poet of his father's day: he increased Jonson's annual pension to £100 and included a tierce of wine and beer.

Thomas Davies called Poetaster "a contemptible mixture of the serio-comic, where the names of Augustus Caesar, Maecenas, Virgil, Horace, Ovid and Tibullus, are all sacrificed upon the altar of private resentment".

Some of his better-known poems are close translations of Greek or Roman models; all display the careful attention to form and style that often came naturally to those trained in classics in the humanist manner.

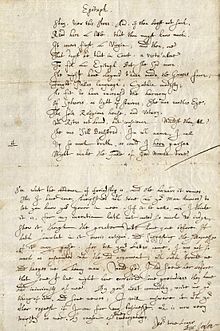

"Epigrams" (published in the 1616 folio) is an entry in a genre that was popular among late-Elizabethan and Jacobean audiences, although Jonson was perhaps the only poet of his time to work in its full classical range.

William Drummond reports that during their conversation, Jonson scoffed at two apparent absurdities in Shakespeare's plays: a nonsensical line in Julius Caesar and the setting of The Winter's Tale on the non-existent seacoast of Bohemia.

[52] In "De Shakespeare Nostrat" in Timber, which was published posthumously and reflects his lifetime of practical experience, Jonson offers a fuller and more conciliatory comment.

It has been argued that Jonson helped to edit the First Folio, and he may have been inspired to write this poem by reading his fellow playwright's works, a number of which had been previously either unpublished or available in less satisfactory versions, in a relatively complete form.

[citation needed] Jonson was a towering literary figure, and his influence was enormous for he has been described as "One of the most vigorous minds that ever added to the strength of English literature".

John Dryden offered a more common assessment in the "Essay of Dramatic Poesie," in which his Avatar Neander compares Shakespeare to Homer and Jonson to Virgil: the former represented profound creativity, the latter polished artifice.

Earlier, Aphra Behn, writing in defence of female playwrights, had pointed to Jonson as a writer whose learning did not make him popular; unsurprisingly, she compares him unfavourably to Shakespeare.

"[59] For the most part, the 18th century consensus remained committed to the division that Pope doubted; as late as the 1750s, Sarah Fielding could put a brief recapitulation of this analysis in the mouth of a "man of sense" encountered by David Simple.

Shortly before the Romantic revolution, Edward Capell offered an almost unqualified rejection of Jonson as a dramatic poet, who (he writes) "has very poor pretensions to the high place he holds among the English Bards, as there is no original manner to distinguish him and the tedious sameness visible in his plots indicates a defect of Genius.

In the 20th century, Jonson's body of work has been subject to a more varied set of analyses, broadly consistent with the interests and programmes of modern literary criticism.

In an essay printed in The Sacred Wood, T. S. Eliot attempted to repudiate the charge that Jonson was an arid classicist by analysing the role of imagination in his dialogue.

Eliot was appreciative of Jonson's overall conception and his "surface", a view consonant with the modernist reaction against Romantic criticism, which tended to denigrate playwrights who did not concentrate on representations of psychological depth.

Popular Culture - His "Queen and Huntress" was used, in slightly amended form, by Mike Oldfield on side 4 of his multi Album set, Incantations.The lyrics can be found on his website, confirming its the same poem.