Beringia

At various times, it formed a land bridge referred to as the Bering land bridge, that was up to 1,000 km (620 mi) wide at its greatest extent and which covered an area as large as British Columbia and Alberta together,[2] totaling about 1.6 million km2 (620,000 sq mi), allowing biological dispersal to occur between Asia and North America.

[1] It is believed that a small human population of at most a few thousand arrived in Beringia from eastern Siberia during the Last Glacial Maximum before expanding into the settlement of the Americas sometime after 16,500 years Before Present (YBP).

[12] The remains of Late Pleistocene mammals that had been discovered on the Aleutians and islands in the Bering Sea at the close of the nineteenth century indicated that a past land connection might lie beneath the shallow waters between Alaska and Chukotka.

The underlying mechanism was first thought to be tectonics, but by 1930 changes in the ice mass balance, leading to global sea-level fluctuations were viewed as the cause of the Bering land bridge.

[15][14] The American arctic geologist David Hopkins redefined Beringia to include portions of Alaska and Northeast Asia.

[citation needed] During the last glacial period, enough of the Earth's water became frozen in the great ice sheets covering North America and Europe to cause a drop in sea levels.

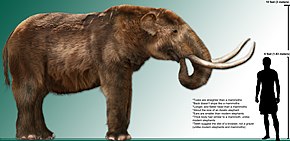

[25] During the Ice Age a vast, cold and dry Mammoth steppe stretched from the arctic islands southwards to China, and from Spain eastwards across Eurasia and over the Bering land bridge into Alaska and the Yukon where it was blocked by the Wisconsin glaciation.

Beringia received more moisture and intermittent maritime cloud cover from the north Pacific Ocean than the rest of the Mammoth steppe, including the dry environments on either side of it.

[29][26][31] There were patches of shrub tundra with isolated refugia of larch (Larix) and spruce (Picea) forests with birch (Betula) and alder (Alnus) trees.

Fossil remains show that spruce, birch and poplar once grew beyond their northernmost range today, indicating that there were periods when the climate was warmer and wetter.

[44] The existence of fauna endemic to the respective Siberian and North American portions of Beringia has led to the 'Beringian Gap' hypothesis, wherein an unconfirmed geographic factor blocked migration across the land bridge when it emerged.

Beringia did not block the movement of most dry steppe-adapted large species such as saiga antelope, woolly mammoth, and caballid horses.

Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by proposed linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.

[77] The governments of Russia and the United States announced a plan to formally establish "a transboundary area of shared Beringian heritage".

[84] Fossil evidence also indicates an exchange of primates and plants between North America and Asia around 55.8 million years ago.

[79] The pattern of bidirectional flow of biota has been asymmetric, with more plants, animals, and fungi generally migrating from Asia to North America than vice versa throughout the Cenozoic.