Bertrand paradox (probability)

The Bertrand paradox is a problem within the classical interpretation of probability theory.

Joseph Bertrand introduced it in his work Calcul des probabilités (1889)[1] as an example to show that the principle of indifference may not produce definite, well-defined results for probabilities if it is applied uncritically when the domain of possibilities is infinite.

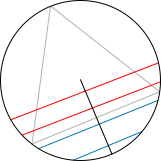

[2] The Bertrand paradox is generally presented as follows:[3] Consider an equilateral triangle that is inscribed in a circle.

Bertrand gave three arguments (each using the principle of indifference), all apparently valid yet yielding different results: [4] The unit circle

in the affine Euclidean plane with the canonical basis and for it, we define a chord as the intersection

(See hereunder in “a way out” Miscellaneous chapter for a formal definition) We consider the unit disk

These three selection methods differ as to the weight they give to chords which are diameters.

This issue can be avoided by "regularizing" the problem so as to exclude diameters, without affecting the resulting probabilities.

[3] But as presented above, in method 1, each chord can be chosen in exactly one way, regardless of whether or not it is a diameter; in method 2, each diameter can be chosen in two ways, whereas each other chord can be chosen in only one way; and in method 3, each choice of midpoint corresponds to a single chord, except the center of the circle, which is the midpoint of all the diameters.

(See hereunder in “a way out” Miscellaneous chapter for a formal definition) Let’s consider a unit disk

And so on… The problem's classical solution (presented, for example, in Bertrand's own work) depends on the method by which a chord is chosen "at random".

[3] The argument is that if the method of random selection is specified, the problem will have a well-defined solution (determined by the principle of indifference).

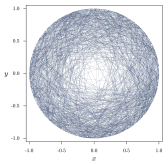

It can be seen very easily that there would be a change for method 3: the chord distribution on the small red circle looks qualitatively different from the distribution on the large circle: The same occurs for method 1, though it is harder to see in a graphical representation.

Jaynes used the integral equations describing the invariances to directly determine the probability distribution.

In a 2015 article,[3] Alon Drory argued that Jaynes' principle can also yield Bertrand's other two solutions.

Drory argues that the mathematical implementation of the above invariance properties is not unique, but depends on the underlying procedure of random selection that one uses (as mentioned above, Jaynes used a straw-throwing method to choose random chords).

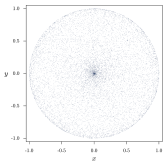

For example, we may consider throwing a dart at the circle, and drawing the chord having the chosen point as its center.

Then the unique distribution which is translation, rotation, and scale invariant is the one called "method 3" above.

It is also the unique scale and rotation invariant distribution for a scenario where a rod is placed vertically over a point on the circle's circumference, and allowed to drop to the horizontal position (conditional on it landing partly inside the circle).

"Method 2" is the only solution that fulfills the transformation invariants that are present in certain physical systems—such as in statistical mechanics and gas physics—in the specific case of Jaynes's proposed experiment of throwing straws from a distance onto a small circle.

For example, in order to arrive at the solution of "method 1", the random endpoints method, one can affix a spinner to the center of the circle, and let the results of two independent spins mark the endpoints of the chord.

In order to arrive at the solution of "method 3", one could cover the circle with molasses and mark the first point that a fly lands on as the midpoint of the chord.

[8] Several observers have designed experiments in order to obtain the different solutions and verified the results empirically.

the event: “To pick up randomly a chord of length greater than p from a unit disk”,

typically the Borel-Lebesgue measure, which may in turn, allow us to calculate the second member of the equality above such as

One way out is to define a chord as a choice of two points on a circle, because assuming for each of them that they follow a unit density probability is not so far-fetched and since this latter depends on the structure of the circle only, and not how we sketch up a chord whatsoever, this should do the job.

And our best bet is to choose it as the probability space of the experiment consisting of randomly picking a point on a circle.

, and the probability space: describes also the odds of the experiment consisting of picking randomly a point on a circle.

Bertrand's precept, which states that probability rarely appears as an obvious or intuitive concept, is truer than ever.

If we assume that the laws of probability are self-evident or straightforward and rely too much on intuition, we risk treading on quicksand and are bound to encounter messy outcomes, such as paradoxes.