Beta decay

The binding energies of all existing nuclides form what is called the nuclear band or valley of stability.

Electron capture is sometimes included as a type of beta decay,[3] because the basic nuclear process, mediated by the weak force, is the same.

In 1900, Becquerel measured the mass-to-charge ratio (m/e) for beta particles by the method of J.J. Thomson used to study cathode rays and identify the electron.

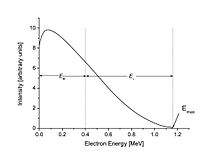

However, the kinetic energy distribution, or spectrum, of beta particles measured by Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn in 1911 and by Jean Danysz in 1913 showed multiple lines on a diffuse background.

[6] In 1914, James Chadwick used a magnetic spectrometer with one of Hans Geiger's new counters to make more accurate measurements which showed that the spectrum was continuous.

[6][7] The results, which appeared to be in contradiction to the law of conservation of energy, were validated by means of calorimetric measurements in 1929 by Lise Meitner and Wilhelm Orthmann.

[9] Beta decay leaves the mass number unchanged, so the change of nuclear spin must be an integer.

From 1920 to 1927, Charles Drummond Ellis (along with Chadwick and colleagues) further established that the beta decay spectrum is continuous.

In 1933, Ellis and Nevill Mott obtained strong evidence that the beta spectrum has an effective upper bound in energy.

Niels Bohr had suggested that the beta spectrum could be explained if conservation of energy was true only in a statistical sense, thus this principle might be violated in any given decay.

In a famous letter written in 1930, Wolfgang Pauli attempted to resolve the beta-particle energy conundrum by suggesting that, in addition to electrons and protons, atomic nuclei also contained an extremely light neutral particle, which he called the neutron.

In 1933, Fermi published his landmark theory for beta decay, where he applied the principles of quantum mechanics to matter particles, supposing that they can be created and annihilated, just as the light quanta in atomic transitions.

Further indirect evidence of the existence of the neutrino was obtained by observing the recoil of nuclei that emitted such a particle after absorbing an electron.

In 1934, Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie bombarded aluminium with alpha particles to effect the nuclear reaction 42He + 2713Al → 3015P + 10n, and observed that the product isotope 3015P emits a positron identical to those found in cosmic rays (discovered by Carl David Anderson in 1932).

This was the first example of β+ decay (positron emission), which they termed artificial radioactivity since 3015P is a short-lived nuclide which does not exist in nature.

[11] The theory of electron capture was first discussed by Gian-Carlo Wick in a 1934 paper, and then developed by Hideki Yukawa and others.

[24] If the captured electron comes from the innermost shell of the atom, the K-shell, which has the highest probability to interact with the nucleus, the process is called K-capture.

The converse, however, is not true: electron capture is the only type of decay that is allowed in proton-rich nuclides that do not have sufficient energy to emit a positron and neutrino.

[24] If the proton and neutron are part of an atomic nucleus, the above described decay processes transmute one chemical element into another.

An often-cited example is the single isotope 6429Cu (29 protons, 35 neutrons), which illustrates three types of beta decay in competition.

Nuclides that are not beta stable have half-lives ranging from under a second to periods of time significantly greater than the age of the universe.

One common example of a long-lived isotope is the odd-proton odd-neutron nuclide 4019K, which undergoes all three types of beta decay (β−, β+ and electron capture) with a half-life of 1.277×109 years.

For allowed decays, the net orbital angular momentum is zero, hence only spin quantum numbers are considered.

[29] Beta decay can be considered as a perturbation as described in quantum mechanics, and thus Fermi's Golden Rule can be applied.

The energy-axis (x-axis) intercept of a Kurie plot corresponds to the maximum energy imparted to the electron/positron (the decay's Q value).

The following table lists the ΔJ and Δπ values for the first few values of L: A very small minority of free neutron decays (about four per million) are "two-body decays": the proton, electron and antineutrino are produced, but the electron fails to gain the 13.6 eV energy necessary to escape the proton, and therefore simply remains bound to it, as a neutral hydrogen atom.

Bound-state β− decays were predicted by Daudel, Jean, and Lecoin in 1947,[41] and the phenomenon in fully ionized atoms was first observed for 163Dy66+ in 1992 by Jung et al. of the Darmstadt Heavy-Ion Research Center.

Likewise, while being stable in the neutral state, the fully ionized 205Tl81+ undergoes bound-state β− decay to 205Pb81+ with a half-life of 291+33−27 days.

In addition, it is estimated that β− decay is energetically impossible for natural atoms but theoretically possible when fully ionized also for 193Ir, 194Au, 202Tl, 215At, 243Am, and 246Bk.

[45] Another possibility is that a fully ionized atom undergoes greatly accelerated β decay, as observed for 187Re by Bosch et al., also at Darmstadt.

β −

decay in an atomic nucleus (the accompanying antineutrino is omitted). The inset shows beta decay of a free neutron. Neither of these depictions shows the intermediate virtual

W −

boson.

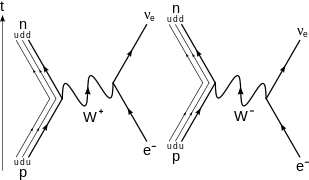

β −

decay of a neutron into a proton , electron , and electron antineutrino via a virtual

W −

boson . For higher-order diagrams see [ 21 ] [ 22 ]

β +

decay of a proton into a neutron , positron , and electron neutrino via an intermediate virtual

W +

boson