Biological pest control

The term "biological control" was first used by Harry Scott Smith at the 1919 meeting of the Pacific Slope Branch of the American Association of Economic Entomologists, in Riverside, California.

The first report of the use of an insect species to control an insect pest comes from "Nanfang Caomu Zhuang" (南方草木狀 Plants of the Southern Regions) (c. 304 AD), attributed to Western Jin dynasty botanist Ji Han (嵇含, 263–307), in which it is mentioned that "Jiaozhi people sell ants and their nests attached to twigs looking like thin cotton envelopes, the reddish-yellow ant being larger than normal.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) initiated research in classical biological control following the establishment of the Division of Entomology in 1881, with C. V. Riley as Chief.

Although the spongy moth was not fully controlled by these natural enemies, the frequency, duration, and severity of its outbreaks were reduced and the program was regarded as successful.

Individuals were caught in New York State and released in Ontario gardens in 1882 by William Saunders, a trained chemist and first Director of the Dominion Experimental Farms, for controlling the invasive currantworm Nematus ribesii.

[14] One of the earliest successes was in controlling Icerya purchasi (cottony cushion scale) in Australia, using a predatory insect Rodolia cardinalis (the vedalia beetle).

[16] Damage from Hypera postica, the alfalfa weevil, a serious introduced pest of forage, was substantially reduced by the introduction of natural enemies.

The alligator weed flea beetle and two other biological controls were released in Florida, greatly reducing the amount of land covered by the plant.

[24] Recommended release rates for Trichogramma in vegetable or field crops range from 5,000 to 200,000 per acre (1 to 50 per square metre) per week according to the level of pest infestation.

[29] Natural enemies are already adapted to the habitat and to the target pest, and their conservation can be simple and cost-effective, as when nectar-producing crop plants are grown in the borders of rice fields.

Providing a suitable habitat, such as a shelterbelt, hedgerow, or beetle bank where beneficial insects such as parasitoidal wasps can live and reproduce, can help ensure the survival of populations of natural enemies.

[32] The providing of artificial shelters in the form of wooden caskets, boxes or flowerpots is also sometimes undertaken, particularly in gardens, to make a cropped area more attractive to natural enemies.

Lady beetles, and in particular their larvae which are active between May and July in the northern hemisphere, are voracious predators of aphids, and also consume mites, scale insects and small caterpillars.

[35] The running crab spider Philodromus cespitum also prey heavily on aphids, and act as a biological control agent in European fruit orchards.

[49] Although there are no quantitative studies of the effectiveness of barn owls for this purpose,[50] they are known rodent predators that can be used in addition to or instead of cats;[51][52] they can be encouraged into an area with nest boxes.

[56] It had been noticed in one study[57] that adult Adalia bipunctata (predator and common biocontrol of Ephestia kuehniella) could survive on flowers but never completed its life cycle, so a meta-analysis[56] was done to find such an overall trend in previously published data, if it existed.

[56] Overall, floral resources (and an imitation, i.e. sugar water) increase longevity and fecundity, meaning even predatory population numbers can depend on non-prey food abundance.

[60] Encarsia formosa is a small parasitoid wasp attacking whiteflies, sap-feeding insects which can cause wilting and black sooty moulds in glasshouse vegetable and ornamental crops.

[65][66] Since most cockroaches remain in the sewer system and sheltered areas which are inaccessible to insecticides, employing active-hunter wasps is a strategy to try and reduce their populations.

[70] Bacillus thuringiensis, a soil-dwelling bacterium, is the most widely applied species of bacteria used for biological control, with at least four sub-species used against Lepidopteran (moth, butterfly), Coleopteran (beetle) and Dipteran (true fly) insect pests.

The bacterium is available to organic farmers in sachets of dried spores which are mixed with water and sprayed onto vulnerable plants such as brassicas and fruit trees.

[77] Beauveria bassiana is mass-produced and used to manage a wide variety of insect pests including whiteflies, thrips, aphids and weevils.

Paecilomyces fumosoroseus is effective against white flies, thrips and aphids; Purpureocillium lilacinus is used against root-knot nematodes, and 89 Trichoderma species against certain plant pathogens.

[82][83] From Chytridiomycota, Synchytrium solstitiale is being considered as a control agent of the yellow star thistle (Centaurea solstitialis) in the United States.

For example, the Lymantria dispar multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus has been used to spray large areas of forest in North America where larvae of the spongy moth are causing serious defoliation.

As part of the campaign against it, from 2003 American scientists and the Chinese Academy of Forestry searched for its natural enemies in the wild, leading to the discovery of several parasitoid wasps, namely Tetrastichus planipennisi, a gregarious larval endoparasitoid, Oobius agrili, a solitary, parthenogenic egg parasitoid, and Spathius agrili, a gregarious larval ectoparasitoid.

Initial results for Tetrastichus planipennisi have shown promise, and it is now being released along with Beauveria bassiana, a fungal pathogen with known insecticidal properties.

Importing the natural enemies of these pests may seem a logical move but this may have unintended consequences; regulations may be ineffective and there may be unanticipated effects on biodiversity, and the adoption of the techniques may prove challenging because of a lack of knowledge among farmers and growers.

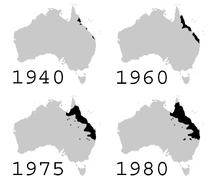

[107] The sturdy and prolific eastern mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki) is a native of the southeastern United States and was introduced around the world in the 1930s and '40s to feed on mosquito larvae and thus combat malaria.

However, it has thrived at the expense of local species, causing a decline of endemic fish and frogs through competition for food resources, as well as through eating their eggs and larvae.