Effects of climate change on agriculture

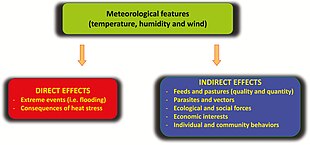

Rising temperatures and changing weather patterns often result in lower crop yields due to water scarcity caused by drought, heat waves and flooding.

[17][18]Agriculture is sensitive to weather, and major events like heatwaves or droughts or heavy rains (also known as low and high precipitation extremes) can cause substantial losses.

[30] The current prediction is that temperatures will increase and precipitation will decrease in arid and semi-arid regions (Middle East, Africa, Australia, Southwest United States, and Southern Europe).

[32][33] Higher winter temperatures and more frost-free days in some regions can currently be disruptive, as they can cause phenological mismatch between flowering time of plants and the activity of pollinators, threatening their reproductive success.

[39]: 747 Much like how climate change is expected to increase overall thermal comfort for humans living in the colder regions of the world,[40] livestock in those places would also benefit from warmer winters.

[41] Across the entire world, however, increasing summertime temperatures as well as more frequent and intense heatwaves will have clearly negative effects, substantially elevating the risk of livestock suffering from heat stress.

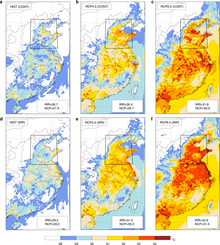

Under the climate change scenario of highest emissions and greatest warming, SSP5-8.5, "cattle,sheep, goats, pigs and poultry in the low latitudes will face 72–136 additional days per year of extreme stress from high heat and humidity".

As such, the 2020–2023 Horn of Africa drought has been primarily attributed to the great increase in evotranspiration exacerbating the effect of persistent low rainfall, which would have been more manageable in the cooler preindustrial climate.

Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, most of the Americas, Australia, South and Southeast Asia are the parts of the globe where droughts are expected to become more frequent and intense in spite of the global increase in precipitation.

[48] Droughts disturb terrestrial precipitation, evaporation and soil moisture,[49][50] and these effects can be aggravated by population growth and urban expansion spurring on increased demand for water.

[51] The ultimate outcome is water scarcity, which results in crop failures and the loss of pasture grazing land for livestock,[52] exacerbating pre-existing poverty in developing countries and leading to malnutrition and potentially famine.

A 2014 meta-analysis has shown that crops and wild plants exposed to elevated carbon dioxide levels at various latitudes have lower density of several minerals such as magnesium, iron, zinc, and potassium.

[101] Erosion, submergence of shorelines, salinity of the water table due to the increased sea levels, could mainly affect agriculture through inundation of low-lying lands.

Combined with higher temperatures, these conditions could favour the development of fungal diseases, such as late blight,[124][109] or bacterial infections such as Ralstonia solanacearum, which may also be able to spread more easily through flash flooding.

[126] For instance, soybean rust is a vicious plant pathogen that can kill off entire fields in a matter of days, devastating farmers and costing billions in agricultural losses.

[128] It found that crop yields across Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and Australia had in general decreased because of climate change (compared to the baseline value of 2004–2008 average data), though exceptions are present.

[128] Even in developed countries such as Australia, extreme weather associated with climate change has been found to cause a wide range of cascading spillovers through supply chain disruption, in addition to its primary effect on fruit, vegetable, and livestock sectors and the rural communities reliant on them.

Further, agricultural expansion has slowed down in the recent years, but this trend is widely expected to reverse in the future in order to maintain the global food supply under all but the most optimistic climate change scenarios consistent with the Paris Agreement.

For instance, even by 2050, some agricultural areas of Australia, Brazil, South Africa, Southeast China, Southern Europe and the United States would suffer production losses of mostly maize and soybeans exceeding 25%.

Studies in Iran surrounding changes in temperature and rainfall are representative for several different parts of the world since there exists a wide range of climatic conditions.

A paper published in the year 2022 found that under the highest-warming SSP5-8.5 scenario, changes in temperature and soil moisture would reduce the aggregate yields of millet, sorghum, maize and soybeans by between 9% and 32%, depending on the model.

[40][172] This causes both mass animal mortality during heatwaves, and the sublethal impacts, such as lower quantity of quality of products like milk, greater vulnerability to conditions like lameness or even impaired reproduction.

[180] Yet, another paper from 2021 suggested that by 2100, under the high-emission SSP5-8.5, 31% and 34% of the current crop and livestock production would leave what the authors have defined as a "safe climatic space": that is, those areas (most of South Asia and the Middle East, as well as parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Central America) would experience very rapid shift in Holdridge life zones (HLZ) and associated weather, while also being low in social resilience.

[182] This corresponds to reaching 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) and 2 °C (3.6 °F) thresholds under that scenario: earlier research suggested that for maize, this would increase risks for multiple simultaneous breadbasket failures (yield loss of 10% or more) from 6% under the late-20th century climate to 40% and 54%, respectively.

[7] As extreme weather events become more common and more intense, floods and droughts can destroy crops and eliminate food supply, while disrupting agricultural activities and rendering workers jobless.

[5]: 717 : 725 Similarly, North China Plain is also expected to be highly affected, in part due to the region's extensive irrigation networks resulting in unusually moist air.

In general, even as climate change would cause increasingly severe effects on food production, most scientists do not anticipate it to result in mass human mortality within this century.

For instance, a 2013 paper estimated that if the high warming of RCP 8.5 scenario was not alleviated by CO2 fertilization effect, it would reduce aggregate yields by 17% by the year 2050: yet, it anticipated that this would be mostly offset through an 11% increase in cropland area.

[215] Suggested potential adaptation strategies to mitigate the effects of global warming on agriculture in Latin America include using plant breeding technologies and installing irrigation infrastructure.

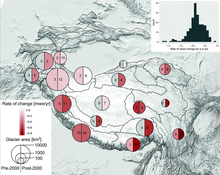

[212] Droughts are becoming more frequent and intense in arid and semiarid western North America as temperatures have been rising, advancing the timing and magnitude of spring snow melt floods and reducing river flow volume in summer.