Spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular.

"Spontaneous generation" means both the supposed processes by which different types of life might repeatedly emerge from specific sources other than seeds, eggs, or parents, and the theoretical principles presented in support of any such phenomena.

Supposed examples included the seasonal generation of mice and other animals from the mud of the Nile, the emergence of fleas from inanimate matter such as dust, or the appearance of maggots in dead flesh.

[8] The physiologoi sought the material principle or arche (Greek: ἀρχή) of things, emphasizing the rational unity of the external world and rejecting theological or mythological explanations.

[9] Anaximander, who believed that all things arose from the elemental nature of the universe, the apeiron (ἄπειρον) or the "unbounded" or "infinite", was likely the first western thinker to propose that life developed spontaneously from nonliving matter.

The primal chaos of the apeiron, eternally in motion, served as a platform on which elemental opposites (e.g., wet and dry, hot and cold) generated and shaped the many and varied things in the world.

[11] The Roman author Censorinus, writing in the 3rd century, reported: Anaximander of Miletus considered that from warmed up water and earth emerged either fish or entirely fishlike animals.

He proposed that plants and animals, including human beings, arose from a primordial terrestrial slime, a mixture of earth and water, combined with the sun's heat.

Another philosopher, Xenophanes, traced the origin of man back to the transitional period between the fluid stage of the Earth and the formation of land, under the influence of the Sun.

[20] While Aristotle recognized that many living things emerged from putrefying matter, he pointed out that the putrefaction was not the source of life, but the byproduct of the action of the "sweet" element of water.

When they are so enclosed, the corporeal liquids being heated, there arises as it were a frothy bubble.With varying degrees of observational confidence, Aristotle theorized the spontaneous generation of a range of creatures from different sorts of inanimate matter.

The testaceans (a genus which for Aristotle included bivalves and snails), for instance, were characterized by spontaneous generation from mud, but differed based upon the precise material they grew in—for example, clams and scallops in sand, oysters in slime, and the barnacle and the limpet in the hollows of rocks.

With the availability of Latin translations, the German philosopher Albertus Magnus and his student Thomas Aquinas raised Aristotelianism to its greatest prominence.

Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra: Act 2, scene 7The author of The Compleat Angler, Izaak Walton repeats the question of the origin of eels "as rats and mice, and many other living creatures, are bred in Egypt, by the sun's heat when it shines upon the overflowing of the river...".

[30] The Brussels physician Jan Baptist van Helmont described a recipe for mice (a piece of dirty cloth plus wheat for 21 days) and scorpions (basil, placed between two bricks and left in sunlight).

[39] Redi used his experiments to support the preexistence theory put forth by the Catholic Church at that time, which maintained that living things originated from parents.

[40] In scientific circles Redi's work very soon had great influence, as evidenced in a letter from the English natural theologian John Ray in 1671 to members of the Royal Society of London, in which he calls the spontaneous generation of insects "unlikely".

[38] But attitudes were changing; by the start of the 19th century, a scientist such as Joseph Priestley could write that "There is nothing in modern philosophy that appears to me so extraordinary, as the revival of what has long been considered as the exploded doctrine of equivocal, or, as Dr. [Erasmus] Darwin calls it, spontaneous generation.

"[43] In 1837, Charles Cagniard de la Tour, a physicist, and Theodor Schwann, one of the founders of cell theory, published their independent discovery of yeast in alcoholic fermentation.

As James Rennie wrote in 1838, despite Redi's experiments, "distinguished naturalists, such as Blumenbach, Cuvier, Bory de St. Vincent, R. Brown, &c." continued to support the theory.

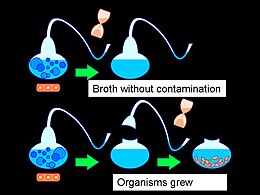

[46] In 1862, the French Academy of Sciences paid special attention to the issue, establishing a prize "to him who by well-conducted experiments throws new light on the question of the so-called spontaneous generation" and appointed a commission to judge the winner.

Heterogenesis was applied to the generation of living things from once-living organic matter (such as boiled broths), and the English physiologist Henry Charlton Bastian proposed the term archebiosis for life originating from non-living materials.