Biogeochemical cycle

Precipitation can seep into the ground and become part of groundwater systems used by plants and other organisms, or can runoff the surface to form lakes and rivers.

Subterranean water can then seep into the ocean along with river discharges, rich with dissolved and particulate organic matter and other nutrients.

There are biogeochemical cycles for many other elements, such as for oxygen, hydrogen, phosphorus, calcium, iron, sulfur, mercury and selenium.

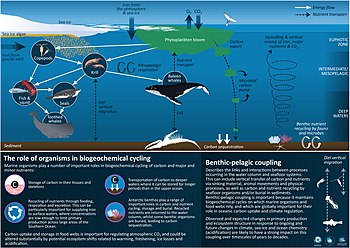

Microorganisms have the ability to carry out wide ranges of metabolic processes essential for the cycling of nutrients and chemicals throughout global ecosystems.

Without microorganisms many of these processes would not occur, with significant impact on the functioning of land and ocean ecosystems and the planet's biogeochemical cycles as a whole.

The cycles are interconnected and play important roles regulating climate, supporting the growth of plants, phytoplankton and other organisms, and maintaining the health of ecosystems generally.

Human activities such as burning fossil fuels and using large amounts of fertilizer can disrupt cycles, contributing to climate change, pollution, and other environmental problems.

Energy flows directionally through ecosystems, entering as sunlight (or inorganic molecules for chemoautotrophs) and leaving as heat during the many transfers between trophic levels.

The six most common elements associated with organic molecules — carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur — take a variety of chemical forms and may exist for long periods in the atmosphere, on land, in water, or beneath the Earth's surface.

Geologic processes, such as weathering, erosion, water drainage, and the subduction of the continental plates, all play a role in this recycling of materials.

Because geology and chemistry have major roles in the study of this process, the recycling of inorganic matter between living organisms and their environment is called a biogeochemical cycle.

In addition to being a part of living organisms, these chemical elements also cycle through abiotic factors of ecosystems such as water (hydrosphere), land (lithosphere), and/or the air (atmosphere).

Although the Earth constantly receives energy from the Sun, its chemical composition is essentially fixed, as the additional matter is only occasionally added by meteorites.

[10][11][12] A key example is that of cultural eutrophication, where agricultural runoff leads to nitrogen and phosphorus enrichment of coastal ecosystems, greatly increasing productivity resulting in algal blooms, deoxygenation of the water column and seabed, and increased greenhouse gas emissions,[13] with direct local and global impacts on nitrogen and carbon cycles.

However, the runoff of organic matter from the mainland to coastal ecosystems is just one of a series of pressing threats stressing microbial communities due to global change.

[14][15][16][17][9] Global change is, therefore, affecting key processes including primary productivity, CO2 and N2 fixation, organic matter respiration/remineralization, and the sinking and burial deposition of fixed CO2.

[17] In addition to this, oceans are experiencing an acidification process, with a change of ~0.1 pH units between the pre-industrial period and today, affecting carbonate/bicarbonate buffer chemistry.

[18] There is also evidence for shifts in the production of key intermediary volatile products, some of which have marked greenhouse effects (e.g., N2O and CH4, reviewed by Breitburg in 2018,[15] due to the increase in global temperature, ocean stratification and deoxygenation, driving as much as 25 to 50% of nitrogen loss from the ocean to the atmosphere in the so-called oxygen minimum zones[19] or anoxic marine zones,[20] driven by microbial processes.

This place is called a reservoir, which, for example, includes such things as coal deposits that are storing carbon for a long period of time.

[23] Plants and animals utilize carbon to produce carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, which can then be used to build their internal structures or to obtain energy.

[25] These models are often used to derive analytical formulas describing the dynamics and steady-state abundance of the chemical species involved.

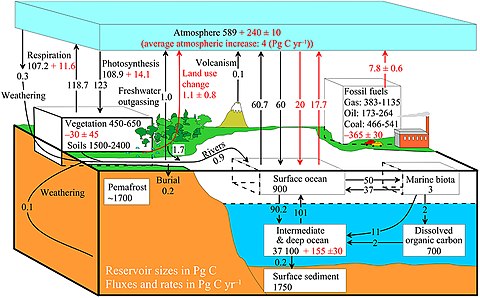

Global biogeochemical box models usually measure: The diagram on the left shows a simplified budget of ocean carbon flows.

The black numbers and arrows indicate the reservoir mass and exchange fluxes estimated for the year 1750, just before the Industrial Revolution.

The red arrows (and associated numbers) indicate the annual flux changes due to anthropogenic activities, averaged over the 2000–2009 time period.

Red numbers in the reservoirs represent the cumulative changes in anthropogenic carbon since the start of the Industrial Period, 1750–2011.

Slow or geological cycles can take millions of years to complete, moving substances through the Earth's crust between rocks, soil, ocean and atmosphere.

This cycle involves relatively short-term biogeochemical processes between the environment and living organisms in the biosphere.

Current knowledge of the microbial ecology of the subsurface is primarily based on 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequences.

Recent estimates show that <8% of 16S rRNA sequences in public databases derive from subsurface organisms[38] and only a small fraction of those are represented by genomes or isolates.