Biomineralization

Biologically formed minerals often have special uses such as magnetic sensors in magnetotactic bacteria (Fe3O4), gravity-sensing devices (CaCO3, CaSO4, BaSO4) and iron storage and mobilization (Fe2O3•H2O in the protein ferritin).

In terms of taxonomic distribution, the most common biominerals are the phosphate and carbonate salts of calcium that are used in conjunction with organic polymers such as collagen and chitin to give structural support to bones and shells.

[5] The structures of these biocomposite materials are highly controlled from the nanometer to the macroscopic level, resulting in complex architectures that provide multifunctional properties.

Because this range of control over mineral growth is desirable for materials engineering applications, there is interest in understanding and elucidating the mechanisms of biologically-controlled biomineralization.

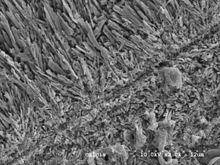

Studies of their significant roles in geological processes, "geomycology", have shown that fungi are involved with biomineralization, biodegradation, and metal-fungal interactions.

[22] The order of most to least oxalic acid secreted by the fungi studied are Aspergillus niger, followed by Serpula himantioides, and finally Trametes versicolor.

[36] The clubbing appendages of the peacock mantis shrimp are made of an extremely dense form of the mineral which has a higher specific strength; this has led to its investigation for potential synthesis and engineering use.

[38] Beyond these main three categories, there are a number of less common types of biominerals, usually resulting from a need for specific physical properties or the organism inhabiting an unusual environment.

[40] Gastropod molluscs living close to hydrothermal vents reinforce their carbonate shells with the iron-sulphur minerals pyrite and greigite.

[41] Magnetotactic bacteria also employ magnetic iron minerals magnetite and greigite to produce magnetosomes to aid orientation and distribution in the sediments.

[54][55] Biogeochemically and ecologically, diatoms are the most important silicifiers in modern marine ecosystems, with radiolarians (polycystine and phaeodarian rhizarians), silicoflagellates (dictyochophyte and chrysophyte stramenopiles), and sponges with prominent roles as well.

[65][66] As a result, biogenic silica structures are used for support,[67] feeding,[68] predation defense [69][70][71] and environmental protection as a component of cyst walls.

[53] Biogenic silica also has useful optical properties for light transmission and modulation in organisms as diverse as plants,[72] diatoms,[73][74][75] sponges,[76] and molluscs.

Mathematical models and controlled experiments of resource competition in phytoplankton have demonstrated the rise to dominance of different algal species based on nutrient backgrounds in defined media.

[85][86] However, the vast diversity of organisms that thrive in a complex array of biotic and abiotic interactions in oceanic ecosystems are a challenge to such minimal models and experimental designs, whose parameterization and possible combinations, respectively, limit the interpretations that can be built on them.

The stability is dependent on the Ca/Mg ratio of seawater, which is thought to be controlled primarily by the rate of sea floor spreading, although atmospheric CO2 levels may also play a role.

[25] Although the biomachinery facilitating biomineralization is complex – involving signalling transmitters, inhibitors, and transcription factors – many elements of this 'toolkit' are shared between phyla as diverse as corals, molluscs, and vertebrates.

[13][97] This suggests that Precambrian organisms were employing the same elements, albeit for a different purpose – perhaps to avoid the inadvertent precipitation of calcium carbonate from the supersaturated Proterozoic oceans.

[96] Forms of mucus that are involved in inducing mineralization in most animal lineages appear to have performed such an anticalcifatory function in the ancestral state.

The most ancient example of biomineralization, dating back 2 billion years, is the deposition of magnetite, which is observed in some bacteria, as well as the teeth of chitons and the brains of vertebrates; it is possible that this pathway, which performed a magnetosensory role in the common ancestor of all bilaterians, was duplicated and modified in the Cambrian to form the basis for calcium-based biomineralization pathways.

[105] Most traditional approaches to the synthesis of nanoscale materials are energy inefficient, requiring stringent conditions (e.g., high temperature, pressure, or pH), and often produce toxic byproducts.

Organic macromolecules collect and transport raw materials and assemble these substrates and into short- and long-range ordered composites with consistency and uniformity.

The term biofilm refers to complex heterogeneous structures comprising different populations of microorganisms that attach and form a community on inert (e.g. rocks, glass, plastic) or organic (e.g. skin, cuticle, mucosa) surfaces.

[111] While the ability to generate ECM appears to be a common feature of multicellular bacterial communities, the means by which these matrices are constructed and function are diverse.

It uses the polymers produced by single cells during biofilm formation as a physical cue to coordinate ECM production by the bacterial community.

Compared to the direct addition of inorganic phosphate to contaminated groundwater, biomineralization has the advantage that the ligands produced by microbes will target uranium compounds more specifically rather than react actively with all aqueous metals.

[citation needed] The International Mineralogical Association (IMA) is the generally recognized standard body for the definition and nomenclature of mineral species.

[125] Recent advances in high-resolution genetics and X-ray absorption spectroscopy are providing revelations on the biogeochemical relations between microorganisms and minerals that may shed new light on this question.

[127] The group's scope includes mineral-forming microorganisms, which exist on nearly every rock, soil, and particle surface spanning the globe to depths of at least 1,600 metres below the sea floor and 70 kilometres into the stratosphere (possibly entering the mesosphere).

[142][143][144][145] The search for evidence of habitability, taphonomy (related to fossils), and organic carbon on the planet Mars is now a primary NASA objective.

(b) Fungi as heterotrophs, recycle organic matter . While doing so, they produce metabolites such as organic acids that can also precipitate as secondary minerals (salts). Recycling organic matter eventually releases constitutive elements such as C, N, P, and S

(c) CO 2 produced by heterotrophic fungal respiration can dissolve into H 2 O and depending on the physicochemical conditions precipitate as CaCO 3 leading to the formation of a secondary mineral.