Bird anatomy

A flexible neck allows many birds with immobile eyes to move their head more productively and center their sight on objects that are close or far in distance.

[8] Most birds have about three times as many neck vertebrae as humans, which allows for increased stability during fast movements such as flying, landing, and taking-off.

[20] As the avian lineage has progressed and as pedomorphosis has occurred, they have lost the postorbital bone behind the eye, the ectopterygoid at the back of the palate, and teeth.

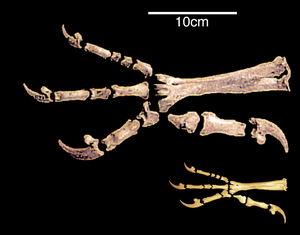

A significant similarity in the structure of the hind limbs of birds and other dinosaurs is associated with their ability to walk on two legs, or bipedalism.

In general, the anisodactyl foot, which also has a better grasping ability and allows confident movement both on the ground and along branches, is ancestral for birds.

Against this background, pterosaurs stand out, which, in the process of unsuccessful evolutionary changes, could not fully move on two legs, but instead developed a physical means of flight[further explanation needed] that was fundamentally different from birds.

[37] Changes in the hindlimbs did not affect the location of the forelimbs, which in birds remained laterally spaced, and in non-avian dinosaurs they switched to a parasagittal orientation.

According to the arboreal hypothesis, the ancestors of birds climbed trees with the help of their forelimbs, and from there they planned, after which they proceeded to flight.

[40] Birds have unique necks which are elongated with complex musculature as it must allow for the head to perform functions other animals may utilize pectoral limbs for.

However, histological and evolutionary developmental work in this area revealed that these structures lack beta-keratin (a hallmark of reptilian scales) and are entirely composed of alpha-keratin.

The bills of many waders have Herbst corpuscles which help them find prey hidden under wet sand, by detecting minute pressure differences in the water.

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure of birds which is used for eating and for preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food, courtship and feeding young.

[57][58] The walls of the air sacs do not have a good blood supply and so do not play a direct role in gas exchange.

Birds lack a diaphragm, and therefore use their intercostal and abdominal muscles to expand and contract their entire thoraco-abdominal cavities, thus rhythmically changing the volumes of all their air sacs in unison (illustration on the right).

During inhalation, environmental air initially enters the bird through the nostrils from where it is heated, humidified, and filtered in the nasal passages and upper parts of the trachea.

Each pair of dorso-ventrobronchi is connected by a large number of parallel microscopic air capillaries (or parabronchi) where gas exchange occurs.

When the contents of all capillaries mix, the final partial pressure of oxygen of the mixed pulmonary venous blood is higher than that of the exhaled air,[59][61] but is nevertheless less than half that of the inhaled air,[59] thus achieving roughly the same systemic arterial blood partial pressure of oxygen as mammals do with their bellows-type lungs.

In comparison to the mammalian respiratory tract, the dead space volume in a bird is, on average, 4.5 times greater than it is in mammals of the same size.

In some birds (e.g. the whooper swan, Cygnus cygnus, the white spoonbill, Platalea leucorodia, the whooping crane, Grus americana, and the helmeted curassow, Pauxi pauxi) the trachea, which some cranes can be 1.5 m long,[59] is coiled back and forth within the body, drastically increasing the dead space ventilation.

This unorganized network of microscopic tubes branches off from the posterior air sacs, and open haphazardly into both the dorso- and ventrobronchi, as well as directly into the intrapulmonary bronchi.

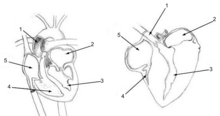

This adaptation allows for an efficient nutrient and oxygen transport throughout the body, providing birds with energy to fly and maintain high levels of activity.

The proventriculus is a rod shaped tube, which is found between the esophagus and the gizzard, that secretes hydrochloric acid and pepsinogen into the digestive tract.

Most birds are unable to swallow by the "sucking" or "pumping" action of peristalsis in their esophagus (as humans do), and drink by repeatedly raising their heads after filling their mouths to allow the liquid to flow by gravity, a method usually described as "sipping" or "tipping up".

[74][76] In addition, specialized nectar feeders like sunbirds (Nectariniidae) and hummingbirds (Trochilidae) drink by using protrusible grooved or trough-like tongues, and parrots (Psittacidae) lap up water.

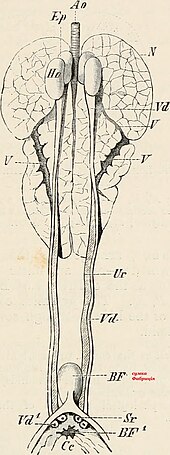

[88][89] The longer and more complicated phalli tend to occur in waterfowl whose females have unusual anatomical features of the vagina (such as dead end sacs and clockwise coils).

Some birds, such as pigeons, geese, and red-crowned cranes, remain with their mates for life and may produce offspring on a regular basis.

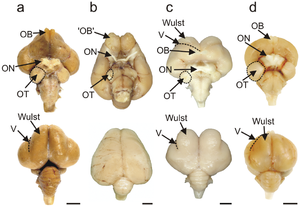

Birds possess large, complex brains, which process, integrate, and coordinate information received from the environment and make decisions on how to respond with the rest of the body.

The telencephalon is dominated by a large pallium, which corresponds to the mammalian cerebral cortex and is responsible for the cognitive functions of birds.

Birds have acute eyesight—raptors (birds of prey) have vision eight times sharper than humans—thanks to higher densities of photoreceptors in the retina (up to 1,000,000 per square mm in Buteos, compared to 200,000 for humans), a high number of neurons in the optic nerves, a second set of eye muscles not found in other animals, and, in some cases, an indented fovea which magnifies the central part of the visual field.

Ossicles within green finches, blackbirds, song thrushes, and house sparrows are proportionately shorter to those found in pheasants, Mallard ducks, and sea birds.

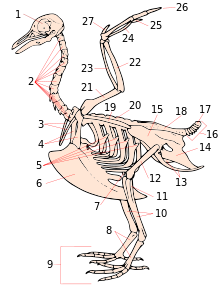

- skull

- cervical vertebrae

- furcula

- coracoid

- uncinate processes of ribs

- keel

- patella

- tarsometatarsus

- digits

- tibia ( tibiotarsus )

- fibula ( tibiotarsus )

- femur

- ischium ( innominate )

- pubis (innominate)

- ilium (innominate)

- caudal vertebrae

- pygostyle

- synsacrum

- scapula

- dorsal vertebrae

- humerus

- ulna

- radius

- Carpometacarpus

- Digit III

- Digit II

- Digit I ( alula )

- Beak

- Head

- Iris

- Pupil

- Mantle

- Lesser coverts

- Scapulars

- Coverts

- Tertials

- Rump

- Primaries

- Vent

- Thigh

- Tibio-tarsal articulation

- Tarsus

- Feet

- Tibia

- Belly

- Flanks

- Breast

- Throat

- Wattle

- Eyestripe

| Color | Vertebral section |

|---|---|

| Pink | Cervical vertebrae |

| Orange | Thoracic/dorsal vertebrae |

| Yellow | Synsacrum |

| Green | Caudal vertebrae |

| Blue | Pygostyle |

(right foot diagrams)