Skull

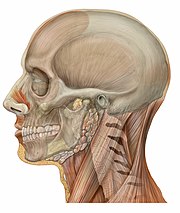

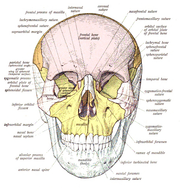

The cranial bones are joined at firm fibrous junctions called sutures and contains many foramina, fossae, processes, and sinuses.

In zoology, the openings in the skull are called fenestrae, the most prominent of which is the foramen magnum, where the brainstem goes through to join the spinal cord.

In human anatomy, the neurocranium (or braincase), is further divided into the calvarium and the endocranium, together forming a cranial cavity that houses the brain.

The interior periosteum forms part of the dura mater, the facial skeleton and splanchnocranium with the mandible being its largest bone.

Functions of the skull include physical protection for the brain, providing attachments for neck muscles, facial muscles and muscles of mastication, providing fixed eye sockets and outer ears (ear canals and auricles) to enable stereoscopic vision and sound localisation, forming nasal and oral cavities that allow better olfaction, taste and digestion, and contributing to phonation by acoustic resonance within the cavities and sinuses.

In some animals such as ungulates and elephants, the skull also has a function in anti-predator defense and sexual selection by providing the foundation for horns, antlers and tusks.

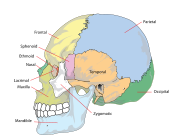

Some of these bones—the occipital, parietal, frontal, in the neurocranium, and the nasal, lacrimal, and vomer, in the facial skeleton are flat bones.

Their known functions are the lessening of the weight of the skull, the aiding of resonance to the voice and the warming and moistening of the air drawn into the nasal cavity.

The largest of these is the foramen magnum, of the occipital bone, that allows the passage of the spinal cord as well as nerves and blood vessels.

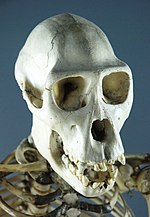

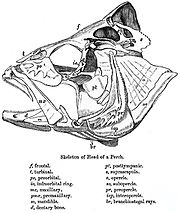

The simpler structure is found in jawless fish, in which the cranium is normally represented by a trough-like basket of cartilaginous elements only partially enclosing the brain, and associated with the capsules for the inner ears and the single nostril.

The cranium is a single structure forming a case around the brain, enclosing the lower surface and the sides, but always at least partially open at the top as a large fontanelle.

The most anterior part of the cranium includes a forward plate of cartilage, the rostrum, and capsules to enclose the olfactory organs.

Finally, the skull tapers towards the rear, where the foramen magnum lies immediately above a single condyle, articulating with the first vertebra.

The roof of the skull is generally well formed, and although the exact relationship of its bones to those of tetrapods is unclear, they are usually given similar names for convenience.

The skull roof is not fully formed, and consists of multiple, somewhat irregularly shaped bones with no direct relationship to those of tetrapods.

The skull roof is formed of a series of plate-like bones, including the maxilla, frontals, parietals, and lacrimals, among others.

Finally, the lower jaw is composed of multiple bones, only the most anterior of which (the dentary) is homologous with the mammalian mandible.

The eye occupies a considerable amount of the skull and is surrounded by a sclerotic eye-ring, a ring of tiny bones.

Living amphibians typically have greatly reduced skulls, with many of the bones either absent or wholly or partly replaced by cartilage.

The endocranium, the bones supporting the brain (the occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid) are largely formed by endochondral ossification.

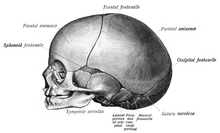

The bones of the roof of the skull are initially separated by regions of dense connective tissue called fontanelles.

This growth can put a large amount of tension on the "obstetrical hinge", which is where the squamous and lateral parts of the occipital bone meet.

As growth and ossification progress, the connective tissue of the fontanelles is invaded and replaced by bone creating sutures.

The anterior fontanelle is located at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones; it is a "soft spot" on a baby's forehead.

In March 2013, for the first time in the U.S., researchers replaced a large percentage of a patient's skull with a precision, 3D-printed polymer implant.

[22] A study conducted in 2018 by the researchers of Harvard Medical School in Boston, funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH), suggested that instead of travelling via blood, there are "tiny channels" in the skull through which the immune cells combined with the bone marrow reach the areas of inflammation after an injury to the brain tissues.

Cords and wooden boards would be used to apply pressure to an infant's skull and alter its shape, sometimes quite significantly.

Forensic scientists and archaeologists use quantitative and qualitative traits to estimate what the bearer of the skull looked like.

[citation needed] The German physician Franz Joseph Gall in around 1800 formulated the theory of phrenology, which attempted to show that specific features of the skull are associated with certain personality traits or intellectual capabilities of its owner.

[citation needed] In the mid-nineteenth century, anthropologists found it crucial to distinguish between male and female skulls.