Birmingham campaign

[4] Protests in Birmingham began with a boycott led by Shuttlesworth meant to pressure business leaders to open employment to people of all races, and end segregation in public facilities, restaurants, schools, and stores.

Organizer Wyatt Tee Walker joined Birmingham activist Shuttlesworth and began what they called Project C, a series of sit-ins and marches intended to provoke mass arrests.

It burnished King's reputation, ousted Connor from his job, forced desegregation in Birmingham, and directly paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which prohibited racial discrimination in hiring practices and public services throughout the United States.

[20] After Shuttlesworth was arrested and jailed for violating the city's segregation rules in 1962, he sent a petition to Mayor Art Hanes' office asking that public facilities be desegregated.

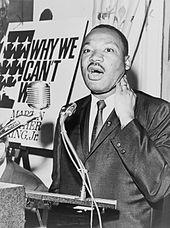

[25][26] King summarized the philosophy of the Birmingham campaign when he said: "The purpose of ... direct action is to create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation".

[27] A significant factor in the success of the Birmingham campaign was the structure of the city government and the personality of its contentious Commissioner of Public Safety, Eugene "Bull" Connor.

Described as an "arch-segregationist" by Time magazine, Connor asserted that the city "ain't gonna segregate no niggers and whites together in this town [sic]".

They caused downtown business to decline by as much as 40 percent, which attracted attention from Chamber of Commerce president Sidney Smyer, who commented that the "racial incidents have given us a black eye that we'll be a long time trying to forget".

For six weeks supporters of the boycott patrolled the downtown area to make sure black shoppers were not patronizing stores that promoted or tolerated segregation.

[25] Wyatt Tee Walker, one of the SCLC founders and the executive director from 1960 to 1964, planned the tactics of the direct action protests, specifically targeting Bull Connor's tendency to react to demonstrations with violence: "My theory was that if we mounted a strong nonviolent movement, the opposition would surely do something to attract the media, and in turn induce national sympathy and attention to the everyday segregated circumstance of a person living in the Deep South.

[43] The campaign used a variety of nonviolent methods of confrontation, including sit-ins at libraries and lunch counters, kneel-ins by black visitors at white churches, and a march to the county building to mark the beginning of a voter-registration drive.

When one black woman entered Loveman's department store to buy her children Easter shoes, a white saleswoman said to her, "Negro, ain't you ashamed of yourself, your people out there on the street getting put in jail and you in here spending money and I'm not going to sell you any, you'll have to go some other place.

[51] In a press release they explained, "We are now confronted with recalcitrant forces in the Deep South that will use the courts to perpetuate the unjust and illegal systems of racial separation".

When historian Jonathan Bass wrote of the incident in 2001, he noted that news of King's incarceration was spread quickly by Wyatt Tee Walker, as planned.

[25] Using scraps of paper given to him by a janitor, notes written on the margins of a newspaper, and later a legal pad given to him by SCLC attorneys, King wrote his essay "Letter from Birmingham Jail".

It responded to eight politically moderate white clergymen who accused King of agitating local residents and not giving the incoming mayor a chance to make any changes.

[60] To re-energize the campaign, SCLC organizer James Bevel devised a controversial alternative plan he named D Day that was later called the "Children's Crusade" by Newsweek magazine.

Birmingham's black radio station, WENN, supported the new plan by telling students to arrive at the demonstration meeting place with a toothbrush to be used in jail.

[71] Kennedy was reported in The New York Times as saying, "an injured, maimed, or dead child is a price that none of us can afford to pay", although adding, "I believe that everyone understands their just grievances must be resolved.

[61] When they continued, Connor ordered the city's fire hoses, set at a level that would peel bark off a tree or separate bricks from mortar, to be turned on the children.

[78] Black parents and adults who were observing cheered on the marching students, but when the hoses were turned on, bystanders began to throw rocks and bottles at the police.

[79][80] Horrified at what the Birmingham police were doing to protect segregation, New York Senator Jacob K. Javits declared, "the country won't tolerate it", and pressed Congress to pass a civil rights bill.

"[90] Birmingham's fire department refused orders from Connor to turn the hoses on demonstrators again,[91] and waded through the basement of the 16th Street Baptist Church to clean up water from earlier fire-hose flooding.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy prepared to activate the Alabama National Guard and notified the Second Infantry Division from Fort Benning, Georgia that it might be deployed to Birmingham.

On May 10, Fred Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King Jr. told reporters that they had an agreement from the City of Birmingham to desegregate lunch counters, restrooms, drinking fountains and fitting rooms within 90 days, and to hire black people in stores as salesmen and clerks.

[106] By May 13, three thousand federal troops were deployed to Birmingham to restore order, even though Alabama Governor George Wallace told President Kennedy that state and local forces were sufficient.

"[116] Despite the apparent lack of immediate local success after the Birmingham campaign, Fred Shuttlesworth and Wyatt Tee Walker pointed to its influence on national affairs as its true impact.

On September 15, 1963, Birmingham again earned international attention when Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church on a Sunday morning and killed four young girls.

Two days after King and Shuttlesworth announced the settlement in Birmingham, Medgar Evers of the NAACP in Jackson, Mississippi demanded a biracial committee to address concerns there.

In 1965 Shuttlesworth assisted Bevel, King, and the SCLC to lead the Selma to Montgomery marches, intended to increase voter registration among black citizens.