Bisection

In geometry, bisection is the division of something into two equal or congruent parts (having the same shape and size).

and Pythagoras' theorem: Property (D) is usually used for the construction of a perpendicular bisector: In classical geometry, the bisection is a simple compass and straightedge construction, whose possibility depends on the ability to draw arcs of equal radii and different centers: The segment

is bisected by drawing intersecting circles of equal radius

The line determined by the points of intersection of the two circles is the perpendicular bisector of the segment.

is a normal vector of the perpendicular line segment bisector.

Perpendicular line segment bisectors were used solving various geometric problems: Its vector equation is literally the same as in the plane case:

Property (D) (see above) is literally true in space, too: (D) The perpendicular bisector plane of a segment

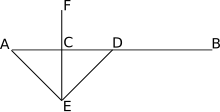

[1] To bisect an angle with straightedge and compass, one draws a circle whose center is the vertex.

The intersection of the circles (two points) determines a line that is the angle bisector.

The proof of the correctness of this construction is fairly intuitive, relying on the symmetry of the problem.

The trisection of an angle (dividing it into three equal parts) cannot be achieved with the compass and ruler alone (this was first proved by Pierre Wantzel).

[3]: p.149 Three intersection points, each of an external angle bisector with the opposite extended side, are collinear (fall on the same line as each other).[3]: p.

149 Three intersection points, two of them between an interior angle bisector and the opposite side, and the third between the other exterior angle bisector and the opposite side extended, are collinear.[3]: p.

149 The angle bisector theorem is concerned with the relative lengths of the two segments that a triangle's side is divided into by a line that bisects the opposite angle.

, then[5] No two non-congruent triangles share the same set of three internal angle bisector lengths.

[6][7] There exist integer triangles with a rational angle bisector.

The internal angle bisectors of a convex quadrilateral either form a cyclic quadrilateral (that is, the four intersection points of adjacent angle bisectors are concyclic),[8] or they are concurrent.

The excenter of an ex-tangential quadrilateral lies at the intersection of six angle bisectors.

The three medians intersect each other at a point which is called the centroid of the triangle, which is its center of mass if it has uniform density; thus any line through a triangle's centroid and one of its vertices bisects the opposite side.

The centroid is twice as close to the midpoint of any one side as it is to the opposite vertex.

The interior perpendicular bisector of a side of a triangle is the segment, falling entirely on and inside the triangle, of the line that perpendicularly bisects that side.

The three perpendicular bisectors of a triangle's three sides intersect at the circumcenter (the center of the circle through the three vertices).

In an acute triangle the circumcenter divides the interior perpendicular bisectors of the two shortest sides in equal proportions.

If the quadrilateral is cyclic (inscribed in a circle), these maltitudes are concurrent at (all meet at) a common point called the "anticenter".

Brahmagupta's theorem states that if a cyclic quadrilateral is orthodiagonal (that is, has perpendicular diagonals), then the perpendicular to a side from the point of intersection of the diagonals always bisects the opposite side.

The envelope of the infinitude of area bisectors is a deltoid (broadly defined as a figure with three vertices connected by curves that are concave to the exterior of the deltoid, making the interior points a non-convex set).

The three cleavers concur at (all pass through) the center of the Spieker circle, which is the incircle of the medial triangle.

[12] Any line through the midpoint of a parallelogram bisects the area[11] and the perimeter.

All area bisectors and perimeter bisectors of a circle or other ellipse go through the center, and any chords through the center bisect the area and perimeter.

Thus any plane containing a bimedian (connector of opposite edges' midpoints) of a tetrahedron bisects the volume of the tetrahedron[13][14]: pp.89–90 This article incorporates material from Angle bisector on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.