Black Monday (1987)

The fall may have been accelerated by portfolio insurance hedging (using computer-based models to buy or sell index futures in various stock market conditions) or a self-reinforcing contagion of fear.

The central banks of the United States, West Germany, and Japan provided market liquidity to prevent debt defaults among financial institutions, and the impact on the real economy was relatively limited and short-lived.

However, refusal to loosen monetary policy by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand had sharply negative and relatively long-term consequences for both its financial markets and real economy.

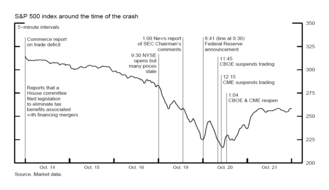

[9] On the morning of Wednesday, October 14, 1987, the United States House Committee on Ways and Means introduced a bill to reduce the tax benefits associated with financing mergers and leveraged buyouts.

Unexpectedly high trade deficit figures announced on October 14 by the United States Department of Commerce had a further negative impact on the value of the US dollar while pushing interest rates upward and stock prices downward.

[13] Moreover, some large mutual fund groups had procedures that enabled customers to easily redeem their shares during the weekend at the same prices that existed at the close of market on Friday.

[35] On the morning of October 20, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan made a brief statement: "The Federal Reserve, consistent with its responsibilities as the Nation's central bank, affirmed today its readiness to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system".

[45] As economist Ben Bernanke (who was later to become Chairman of the Federal Reserve) wrote: The Fed's key action was to induce the banks (by suasion and by the supply of liquidity) to make loans, on customary terms, despite chaotic conditions and the possibility of severe adverse selection of borrowers.

These included trading curbs such as a sharp limit on price movements of a share of more than 10 to 15 percent; restrictions and institutional barriers to short-selling by domestic and international traders; frequent adjustments of margin requirements in response to changes in volatility; strict guidelines on mutual fund redemptions; and actions of the Ministry of Finance to control the total shares of stock and exert moral suasion on the securities industry.

[51] In its biggest-ever single fall, the Hang Seng Index of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange fell by 420.81 points, eliminating HK$65 billion' (10 percent) of its share value.

[58] Their decision was motivated in part by the high risk that a market collapse would have serious consequences for the entire financial system of Hong Kong, and perhaps result in rioting, with the added threat of intervention by the army of the People's Republic of China.

[59] According to Neil Gunningham, a further motivation was brought on by a significant conflict of interest: many of these committee members were themselves futures brokers, and their firms were in danger of substantial defaults from their clients.

It was composed heavily of small, local investors who were relatively uninformed and unsophisticated, had only a short-term commitment to the market, and whose goals were primarily speculative rather than hedging.

Although on paper the Hong Kong exchange's margin requirements were in line with those of other major markets, in practice brokers regularly extended credit with little regard for risk.

"[69] Finally, in the interest of preserving political stability and public order, the then British colonial government was forced to rescue the Guarantee Fund by providing a bail-out package of HK$4 billion.

[75] Holding onto a disinflationary stance, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand declined to loosen monetary policy – which would have helped firms settle their obligations and remain in operation.

[77] As the harmful effects spread over the next few years, major corporations and financial institutions went out of business, and the banking systems of New Zealand and Australia were impaired, contributing to a "long recession".

[83] Other factors often cited include a general feeling that stocks were overvalued and were certain to undergo a correction, the decline of the dollar, persistent trade and budget deficits, and rising interest rates.

[82] According to Shiller, the most common responses to his survey were related to a general mindset of investors at the time: a "gut feeling" of an impending crash, perhaps driven by excessive debt.

[83] This aligns with an account suggested by economist Martin Feldstein, who has made the argument that several of these institutional and market factors exerted pressure in an environment of general anxiety.

[84] Yet investors were also hesitant to make this move: "...everybody knew the market was overpriced, but everybody was greedy and didn't want to miss out on a continuation of the wonderful rise that had been going on since the beginning of the year.

These factors and others motivated the industrialized nations (and in particular, the US, Japan and West Germany) to reach the Louvre agreement with several related goals in mind, one of which was to keep a floor beneath the value of the dollar while holding exchange rates within a specified band or reference range of one another.

[88] The central banks of Japan and West Germany had been vocal about their fears of rising inflation; this created an expectation that these countries would raise interest rates to reduce liquidity and quell inflationary pressures.

[92] They raised the prospect of a currency war, or even the collapse of the dollar,[93] an anonymous senior Reagan administration later summarized the fear and uncertainty in investor's minds after Baker's statement: ...wait a minute.

[107] This strategy became a source of downward pressure when portfolio insurers whose computer models noted that stocks opened lower and continued their steep price decline.

[112] More to the point, the cross-market analysis of Richard Roll, for example, found that markets with a greater prevalence of computerized trading (including portfolio insurance) actually experienced relatively less severe losses (in percentage terms) than those without.

[118] Investors vary between seemingly rational and irrational behaviors as they "struggle to find their way between the give and take, between risk and return, one moment engaging in cool calculation and the next yielding to emotional impulses".

[119] If noise is misinterpreted as meaningful news, then the reactions of risk-averse traders and arbitrageurs will bias the market, preventing it from establishing prices that accurately reflect the fundamental state of the underlying stocks.

[122] Moreover, Lawrence A. Cunningham has suggested that while noise theory is "supported by substantial empirical evidence and a well-developed intellectual foundation", it makes only a partial contribution toward explaining events such as the crash of October 1987.

They later resumed some interventions on behalf of the dollar until December 1988, but eventually it became clear that "international currency coordination of any kind, including a target zone, is not possible.