Blackletter

[1] It continued to be commonly used for Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish until the 1870s,[2] Finnish until the turn of the 20th century,[3] Latvian until the 1930s,[4] and for the German language until the 1940s, when Hitler officially discontinued it in 1941.

Blackletter developed from Carolingian as an increasingly literate 12th-century Europe required new books in many different subjects.

New universities were founded, each producing books for business, law, grammar, history and other pursuits, not solely religious works, for which earlier scripts typically had been used.

[citation needed] Its large size consumed a lot of manuscript space in a time when writing materials were very costly.

[citation needed] Flavio Biondo, in Italia Illustrata (1474), wrote that the Germanic Lombards invented this script after they invaded Italy in the 6th century.

It was in fact invented in the reign of Charlemagne, although only used significantly after that era, and actually formed the basis for the later development of blackletter.

As universities began to populate Europe, a need for a more rapid writing technology led to the development of this script.

As the script continued to evolve and become ever more angular, vertical and compressed, it began its transition to the textura hands.

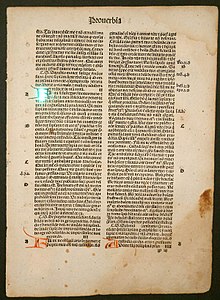

Johannes Gutenberg carved a textualis typeface—including a large number of ligatures and common abbreviations—when he printed his 42-line Bible.

The Donatus-Kalender (also known as Donatus-und-Kalender or D-K) is the name for the metal type design that Gutenberg used in his earliest surviving printed works, dating from the early 1450s.

[10] The practice of setting foreign words or phrases in antiqua within a blackletter text does not apply to loanwords that have been incorporated into the language.

The University of Oxford borrowed the littera parisiensis in the 13th century and early 14th century, and the littera oxoniensis form is almost indistinguishable from its Parisian counterpart; however, there are a few differences, such as the round final ⟨s⟩ forms, resembling the number ⟨8⟩, rather than the long ⟨s⟩ used in the final position in the Paris script.

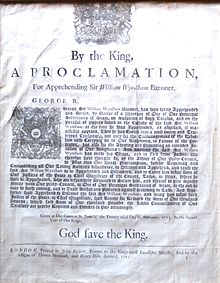

[11] However, blackletter was considered to be more readily legible (especially by the less literate classes of society), and it therefore remained in use throughout the 17th century and into the 18th for documents intended for widespread dissemination, such as proclamations and Acts of Parliament, and for literature aimed at the common people, such as ballads, chivalric romances, and jokebooks.

The legacy of these English cursive Gothic forms survived in common use as late as the 18th century in the court hand used for some legal records.

French textualis was tall and narrow compared to other national forms, and was most fully developed in the late 13th century in Paris.

In the 13th century there also was an extremely small version of textualis used to write miniature Bibles, known as "pearl script".

Another form of French textualis in this century was the script developed at the University of Paris, littera parisiensis, which also is small in size and designed to be written quickly, not calligraphically.

Bastarda, the "hybrid" mixture of cursiva and textualis, developed in the 15th century and was used for vernacular texts as well as Latin.

Most importantly, all of the works of Martin Luther, leading to the Protestant Reformation, as well as the Apocalypse of Albrecht Dürer (1498), used this typeface.

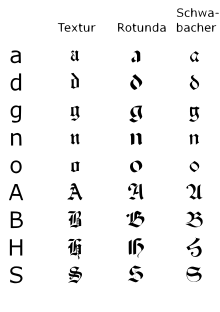

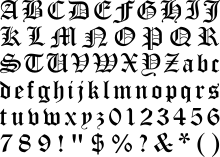

German-made Textualis type is usually very heavy and angular, and there are few characteristic features that are common to all occurrences of the script.

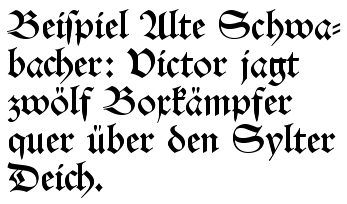

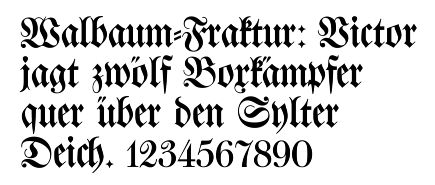

Schwabacher, a blackletter with more rounded letters, soon became the usual printed typeface, but it was replaced by Fraktur in the early 17th century.

A hybrida form, which was basically cursiva with fewer looped letters and with square proportions similar to textualis, was used in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Italian Rotunda also is characterized by unique abbreviations, such as ⟨q⟩ with a line beneath the bow signifying qui, and unusual spellings, such as ⟨x⟩ for ⟨s⟩ (milex rather than miles).

Just as they later took control of the newspapers, upon the introduction of printing the Jews residing in Germany took control of the printing presses and thus in Germany the Schwabach Jew letters were forcefully introduced.Today the Führer, talking with Herr Reichsleiter Amann and Herr Book Publisher Adolf Müller, has decided that in the future the Antiqua script is to be described as normal script.