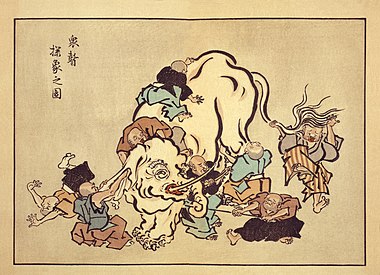

Blind men and an elephant

The Buddhist text Tittha Sutta, Udāna 6.4, Khuddaka Nikaya,[3] contains one of the earliest versions of the story.

In its various versions, it is a parable that has crossed between many religious traditions and is part of Jain, Hindu and Buddhist texts of 1st millennium CE or before.

The tale later became well known in Europe, with 19th-century American poet John Godfrey Saxe creating his own version as a poem, with a final verse that explains that the elephant is a metaphor for God, and the various blind men represent religions that disagree on something no one has fully experienced.

The earliest versions of the parable of blind men and the elephant are found in Buddhist, Hindu and Jain texts, as they discuss the limits of perception and the importance of complete context.

The parable has several Indian variations, but broadly goes as follows:[7][2] A group of blind men heard that a strange animal, called an elephant, had been brought to the town, but none of them were aware of its shape and form.

The last felt its tusk, stating the elephant is that which is hard, smooth and like a spear.In some versions, the blind men then discover their disagreements, suspect the others to be not telling the truth and come to blows.

At various times the parable has provided insight into the relativism, opaqueness or inexpressible nature of truth, the behavior of experts in fields of contradicting theories, the need for deeper understanding, and respect for different perspectives on the same object of observation.

The Rigveda, dated to have been written down (from earlier oral traditions) between 1500 and 1200 BCE, states "Reality is one, though wise men speak of it variously."

According to Paul J. Griffiths, this premise is the foundation of universalist perspective behind the parable of the blind men and an elephant.

For example, Adi Shankara mentions it in his bhasya on verse 5.18.1 of the Chandogya Upanishad as follows: etaddhasti darshana iva jatyandhah Translation: That is like people blind by birth in/when viewing an elephant.

The medieval era Jain texts explain the concepts of anekāntavāda (or "many-sidedness") and syādvāda ("conditioned viewpoints") with the parable of the blind men and an elephant (Andhgajanyāyah), which addresses the manifold nature of truth.

"Due to extreme delusion produced on account of a partial viewpoint, the immature deny one aspect and try to establish another.

"[10] Mallisena also cites the parable when noting the importance of considering all viewpoints in obtaining a full picture of reality.

"The men assert the elephant is either like a pot (the blind man who felt the elephant's head), a winnowing basket (ear), a plowshare (tusk), a plow (trunk), a granary (body), a pillar (foot), a mortar (back), a pestle (tail) or a brush (tip of the tail).

The Buddha then speaks the following verse: O how they cling and wrangle, some who claim For preacher and monk the honored name!

[14] The Persian Sufi poet Sanai (1080–1131/1141 CE) of Ghazni (currently, Afghanistan) presented this teaching story in his The Walled Garden of Truth.

In the poem, each man concluded that the elephant was like a wall, snake, spear, tree, fan or rope, depending upon where they had touched.

This version begins with a conference of scientists, from different fields of expertise, presenting their conflicting conclusions on the material upon which a camera is focused.

As the camera slowly zooms out it gradually becomes clear that the material under examination is the hide of an African elephant.

[31][32][33][34] Ship of Theseus, a 2012 Indian philosophical drama named after the eponymous thought experiment, also references the parable.

[citation needed] Natalie Merchant sang Saxe's poem in full on her Leave Your Sleep album.

(wall relief in Northeast Thailand)