1888 United States presidential election

Grover Cleveland Democratic Benjamin Harrison Republican Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 6, 1888.

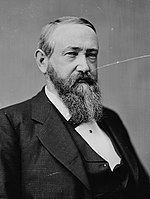

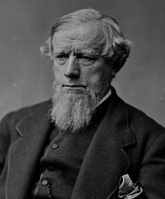

Republican nominee Benjamin Harrison, a former U.S. senator from Indiana, defeated incumbent Democratic President Grover Cleveland of New York.

He defeated other prominent party leaders such as Ohio Senator John Sherman and former Michigan Governor Russell Alger.

Cleveland's opposition to American Civil War pensions and inflated currency also made enemies among veterans and farmers.

Harrison swept almost the entire North and Midwest, including narrowly carrying the swing states of New York and Indiana.

The Republicans hoped to win Indiana's 15 electoral votes, which had gone to Cleveland in the previous presidential election.

Levi P. Morton, a former New York City congressman and ambassador, was nominated for vice-president over William Walter Phelps, his nearest rival.

Former Senator Allen G. Thurman from Ohio was nominated for vice-president over Isaac P. Gray, his nearest rival, and John C. Black, who trailed behind.

[2] The Democratic platform largely confined itself to a defense of the Cleveland administration, supporting reduction in the tariff and taxes generally as well as statehood for the western territories.

The Union Labor Party garnered nearly 150,000 popular votes, but failed to gain widespread national support.

The delegates cast 310 of their 350 ballots for the following ticket: Belva A. Lockwood for president and Alfred H. Love for vice-president.

[12] The Industrial Reform Party National Convention assembled in Grand Army Hall, Washington, DC.

[13] He told the Montgomery Advertiser that he hoped to carry several states, including Alabama, New York, North Carolina, Arkansas, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri.

[14] Cleveland set the main issue of the campaign when he proposed a dramatic reduction in tariffs in his annual message to Congress in December 1887.

Cleveland neatly neutralized this threat by pursuing punitive action against Canada (which, although autonomous, was still part of the British Empire) in a fishing rights dispute.

[19][20] Harrison was well-funded by party activists and mounted an energetic campaign by the standards of the day, giving many speeches from his front porch in Indianapolis that were covered by the newspapers.

[21] William Wade Dudley (1842–1909), an Indianapolis lawyer, was a tireless campaigner and prosecutor of Democratic election frauds.

Although the National Committee had no business meddling in state politics, Dudley wrote a circular letter to Indiana's county chairmen, telling them to "divide the floaters into Blocks of Five, and put a trusted man with the necessary funds in charge of these five, and make them responsible that none get away and that all vote our ticket."

His pre-emptive strike backfired when Democrats obtained the letter and distributed hundreds of thousands of copies nationwide in the last days of the campaign.

[22][23] A California Republican named George Osgoodby wrote a letter to Sir Lionel Sackville-West, the British ambassador to the United States, under the assumed name of "Charles F. Murchison," describing himself as a former Englishman who was now a California citizen and asked how he should vote in the upcoming presidential election.

Sir Lionel wrote back and in the "Murchison letter" indiscreetly suggested that Cleveland was probably the best man from the British point of view.

[28][failed verification][29] Meanwhile, Cleveland won every state in the south via the disenfranchisement of nearly the entire southern black voter base.

Instead, Cleveland became the third of only five candidates to obtain a plurality or majority of the popular vote but lose their respective presidential elections (Andrew Jackson in 1824, Samuel J. Tilden in 1876, Al Gore in 2000, and Hillary Clinton in 2016).

[31] Harrison won the Electoral College by a 233–168 margin, largely by virtue of his 1.09% win in Cleveland's home state of New York.

[33] This was the first time in American history that a party lost re-election after a single four-year term; this would occur again in 1892, but not for Democrats until 1980.

Source: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836–1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247–57.