Bloodstain pattern analysis

[1] At its core, BPA revolves around recognizing and categorizing bloodstain patterns, a task essential for reconstructing events in crimes or accidents, verifying statements made during investigations, resolving uncertainties about involvement in a crime, identifying areas with a high likelihood of offender movement for prioritized DNA sampling, and discerning between homicides, suicides, and accidents.

The most common classification method was created by S. James, P. Kish, and P. Sutton,[4] and it divides bloodstains into three categories: passive, spatter, and altered.

Current classification methods often describe pattern types based on their formation mechanisms rather than observable characteristics, complicating the analysis process.

[5] Ideally, BPA involves meticulous evaluation of pattern characteristics against objective criteria, followed by interpretation to aid crime scene reconstruction.

Dr. Eduard Piotrowski of the University of Kraków published a paper titled "On the formation, form, direction, and spreading of blood stains after blunt trauma to the head.

[13] A 1952 episode of the police procedural radio series Dragnet made reference to bloodstain pattern analysis to reconstruct a shooting incident.

[14] Between 1880 and 1957, courts in Michigan, Mississippi, Ohio, and California rejected expert testimony for bloodspatter analysis, generally holding that it added nothing to the jurors' own evaluations of bloodstains submitted as evidence.

[15] MacDonell testified in court on multiple occasions as an expert of bloodstain analysis, and the legal precedent set by these cases led to its widespread use in American courts, although as early as 1980 some judges expressed strong doubts about its reliability, and it was not always accepted as evidence, especially in states with no prior rulings that relied on such evidence.

[17][18][19] In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences published an examination of forensic methods used in United States courts which harshly criticized both bloodstain pattern analysis and the credentials of the majority of the analysts and experts in the field.

[15][18] Judges have largely ignored the report's findings and continue to accept bloodstain pattern analysis as expert evidence.

[15] In 2013 Daniel Attinger, a fluid dynamics researcher at Columbia University, published a paper on bloodstain pattern analysis in Forensic Science International, finding that many of the central hypotheses of bloodstain analysis remain untested, and that existing analysts often made incorrect assumptions or other errors in their analyses.

This works best for fast-moving drops with flat trajectories, but uncertainties in their curvature may lead to errors in determining the blood source's horizontal position.

[2] Transfer stains occur when two surfaces come into contact and at least one has blood on it, and it includes swipe and wipe patterns, which can give information regarding sequence of movement in some cases.

[2] Pooling occurs when the source of the bleeding remains static for a certain period of time, the blood continuously dripping in the same location and resulting in an important accumulation.

If the individual who is actively bleeding moves while blood is dripping, the resulting pattern will allow for determination of direction and relative speed of movement at that time.

These patterns arise from blood being ejected from a bloodied or bleeding object during its movement, commonly observed in incidents involving physical assaults or strikes.

The reliability of courtroom testimony by bloodstain pattern analysts has come under fire, particularly in the wake of a 2009 report by the National Academy of Sciences,[15] which found the method of analysis to be "subjective rather than scientific", and that it involved an "enormous" degree of uncertainty.

[37] In addition to concerns over methodology, the report criticized the lack of proper certification requirements for analysts and an emphasis on "experience over scientific foundations".

[37] Many bloodstain pattern analysts have testified in court as experts despite having received training only in the form of a 40-hour course taught independently by MacDonell or one of his students, without institutional accreditation or minimum educational requirements.

[15] Even with proper training and methods, there are still many times where reputable analysts disagree on their findings, which calls into question the reliability of their conclusions and its value as evidence in court.

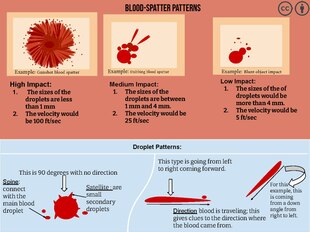

[15] While certain aspects of bloodstain pattern analysis, such as methods for determining the impact speeds of splattered blood, are supported by scientific studies, some analysts go well beyond what is verifiable.

[37] In addition to problems with the underlying scientific validity of the method, the circumstances of bloodstain pattern analyses, which are often conducted at the behest of either the prosecution or the defense in a court case, can introduce confirmation bias into the analyst's assessment.

The prosecution's experts included Tom Bevel and Rod Englert, who testified that the stains were high-velocity impact spatter.

Paul Kish, Barton Epstein, Paulette Sutton, Barrie Goetz, and Stuart H. James testified for the defense that the stains were transferred from his shirt brushing against his daughter's hair.

[18] Dr. Robert Shaler, Founding Director of the Penn State Forensic Science Program, decried blood spatter analysis as unreliable in the Camm case.

Dr. Shaler pointed out that one limitation of blood spatter analysis testimony is that "you do not have the supporting underlying science" to back up your conclusions.