Thermoregulation

[1] Work in 2022 established by experiment that a wet-bulb temperature exceeding 30.55°C caused uncompensable heat stress in young, healthy adult humans.

The rectum has traditionally been considered to reflect most accurately the temperature of internal parts, or in some cases of sex or species, the vagina, uterus or bladder.

[4] Some animals undergo one of various forms of dormancy where the thermoregulation process temporarily allows the body temperature to drop, thereby conserving energy.

[5] Endotherms possess a larger number of mitochondria per cell than ectotherms, enabling them to generate more heat by increasing the rate at which they metabolize fats and sugars.

In ectotherms, the internal physiological sources of heat are of negligible importance; the biggest factor that enables them to maintain adequate body temperatures is due to environmental influences.

An example of behavioral adaptation is that of a lizard lying in the sun on a hot rock in order to heat through radiation and conduction.

Evaporation of water, either across respiratory surfaces or across the skin in those animals possessing sweat glands, helps in cooling body temperature to within the organism's tolerance range.

Animals with a body covered by fur have limited ability to sweat, relying heavily on panting to increase evaporation of water across the moist surfaces of the lungs and the tongue and mouth.

Mammals like cats, dogs and pigs, rely on panting or other means for thermal regulation and have sweat glands only in foot pads and snout.

[citation needed] The physiology of the Dendroctonus micans beetle encompasses a suite of adaptations crucial for its survival and reproduction.

Flight capabilities enable them to disperse and locate new host trees, while sensory organs aid in detecting environmental cues and food sources.

Overall, these adaptations underscore the beetle's remarkable resilience and highlight the significance of understanding their physiology for effective management and conservation efforts.

[20] This organ possesses control mechanisms as well as key temperature sensors, which are connected to nerve cells called thermoreceptors.

[26] Thermoregulation is also an integral part of a reptile's life, specifically lizards such as Microlophus occipitalis and Ctenophorus decresii who must change microhabitats to keep a constant body temperature.

Heat is produced by breaking down the starch that was stored in their roots,[31] which requires the consumption of oxygen at a rate approaching that of a flying hummingbird.

[29] Another theory is that thermogenicity helps attract pollinators, which is borne out by observations that heat production is accompanied by the arrival of beetles or flies.

Over time, the genes selecting for higher heat tolerance were reduced in the population due to the cooler host climate the fly is able to exploit.

They preferentially wrap themselves around the coolest portions of trees, typically near the bottom, to increase their passive radiation of internal body heat.

To remain in "stasis" for long periods, these animals build up brown fat reserves and slow all body functions.

Examples include lady beetles (Coccinellidae),[44] North American desert tortoises, crocodiles, salamanders, cane toads,[45] and the water-holding frog.

[46] Daily torpor occurs in small endotherms like bats and hummingbirds, which temporarily reduces their high metabolic rates to conserve energy.

[52] In humans, a diurnal variation has been observed dependent on the periods of rest and activity, lowest at 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. and peaking at 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monkeys also have a well-marked and regular diurnal variation of body temperature that follows periods of rest and activity, and is not dependent on the incidence of day and night; nocturnal monkeys reach their highest body temperature at night and lowest during the day.

[citation needed] Fever is a regulated elevation of the set point of core temperature in the hypothalamus, caused by circulating pyrogens produced by the immune system.

[citation needed] Some monks are known to practice Tummo, biofeedback meditation techniques, that allow them to raise their body temperatures substantially.

[58][57] In experiments on cats performed by Sutherland Simpson and Percy T. Herring, the animals were unable to survive when rectal temperature fell below 16 °C (61 °F).

Blood that is too warm produces dyspnea by exhausting the metabolic capital of the respiratory centre;[59] heart rate is increased; the beats then become arrhythmic and eventually cease.

He found that species of the same class showed very similar temperature values, those from the Amphibia examined being 38.5 °C, fish 39 °C, reptiles 45 °C, and various molluscs 46 °C.

[citation needed] Also, in the case of pelagic animals, he showed a relation between death temperature and the quantity of solid constituents of the body.

[58] A 2022 study on the effect of heat on young people found that the critical wet-bulb temperature at which heat stress can no longer be compensated, Twb,crit, in young, healthy adults performing tasks at modest metabolic rates mimicking basic activities of daily life was much lower than the 35°C usually assumed, at about 30.55°C in 36–40°C humid environments, but progressively decreased in hotter, dry ambient environments.

The ants have developed a lifestyle of scavenging for short durations during the hottest hours of the day, in excess of 50 °C (122 °F), for the carcasses of insects and other forms of life which have died from heat stress.

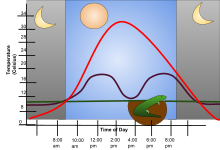

The purple line represents the body temperature of the lizard.

The green line represents the base temperature of the burrow.

Lizards are ectotherms and use behavioral adaptations to control their temperature. They regulate their behavior based on the temperature outside, if it is warm they will go outside up to a point and return to their burrow as necessary.