Bohemia

Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII in his 10th-century work De Administrando Imperio also mentioned the region as Boiki (see White Serbia).

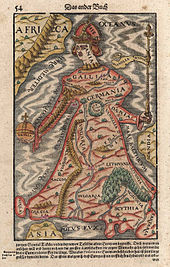

Bohemia, like neighboring Bavaria, is named after the Boii, a large Celtic nation known to the Romans for their migrations and settlement in northern Italy and other places.

Another part of the nation moved west with the Helvetii into southern France, one of the events leading to the interventions of Julius Caesar's Gaulish campaign of 58 BC.

The emigration of the Helvetii and Boii left southern Germany and Bohemia a lightly inhabited "desert" into which Suebic peoples arrived, speaking Germanic languages, and became dominant over remaining Celtic groups.

In the area of modern Bohemia, the Marcomanni and other Suebic groups were led by their king, Marobodus, after being defeated by Roman forces in Germany.

They were able to maintain a strong alliance with neighboring tribes, including (at different times) the Lugii, Quadi, Hermunduri, Semnones, and Buri, which was sometimes partly controlled by the Roman Empire and sometimes in conflict with it; for example, in the second century, they fought Marcus Aurelius.

In late classical times and the early Middle Ages, two new Suebic groupings appeared west of Bohemia in southern Germany, the Alemanni (in the Helvetian desert) and the Bavarians (Baiuvarii).

The last known mention of the Kingdom of the Marcomanni, concerning a queen named Fritigil, is from the fourth century, and she was thought to have lived in or near Pannonia.

The Suebian Langobardi, who moved over many generations from the Baltic Sea, via the Elbe and Pannonia to Italy, recorded in a tribal history a time spent in "Bainaib".

After the Migration Period, Bohemia was partially repopulated around the sixth century, and eventually Slavic tribes arrived from the east, and their language began to replace the older Germanic, Celtic, and Sarmatian ones.

Other sources (Descriptio civitatum et regionum ad septentrionalem plagam Danubii, Bavaria, 800–850) divide the population of Bohemia into the Merehani, Marharaii, Beheimare (Bohemani), and Fraganeo.

They were Slavic-speaking and contributed to the transformation of diverse neighboring populations into a new nation named and led by them with a united "Slavic" ethnic consciousness.

After Svatopluk's death Great Moravia was weakened by years of internal conflict and constant warfare, ultimately collapsing and fragmenting because of continual incursions by invading nomadic Magyars.

The jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Empire was definitively reasserted when Jaromír of Bohemia was granted fief of the Kingdom of Bohemia by Emperor King Henry II of the Holy Roman Empire, with the promise that he hold it as a vassal once he reoccupied Prague with a German army in 1004, ending the rule of Bolesław I of Poland.

Substantial German immigration began in the mid-13th century, as the court sought to replace losses from the brief Mongol invasion of Europe in 1241.

The House of Luxembourg accepted the invitation to the Bohemian throne with the marriage to the Přemyslid heiress, Elizabeth and the crowning subsequent of John I of Bohemia (in the Czech Republic known as Jan Lucemburský) in 1310.

At the same time and place, the teachings of Jan Hus, the rector of Charles University and a prominent reformer and religious thinker, influenced the rise of modern Czech.

Hus was invited to attend the council to defend himself and the Czech positions in the religious court, but with the emperor's approval, he was executed on 6 July 1415.

As the leader of the Hussite armies, he used innovative tactics and weapons, such as howitzers, pistols, and fortified wagons, which were revolutionary for the time and established Žižka as a great general who never lost a battle.

The renewal of the old Bohemian Crown (Kingdom of Bohemia, Margraviate of Moravia, and Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia) became the official political program of both Czech liberal politicians and the majority of Bohemian aristocracy ("state rights program"), while parties representing the German minority and small part of the aristocracy proclaimed their loyalty to the centralist Constitution (so-called "Verfassungstreue").

But Czech political leaders claimed the entire Bohemian lands, including majority German-speaking areas, for Czechoslovakia.

[29] Under its first president, Tomáš Masaryk, Czechoslovakia became a liberal democratic republic, but serious issues emerged regarding the Czech majority's relationship with the German and Hungarian minorities.

After the Munich Agreement in 1938, the border regions of Bohemia historically inhabited predominantly by ethnic Germans (the Sudetenland) were annexed to Nazi Germany.

During World War II, the Germans operated the Theresienstadt Ghetto for Jews, the Dulag Luft Ost, Stalag IV-C and Stalag 359 prisoner-of-war camps for French, British, Belgian, Serbian, Dutch, Slovak, Soviet, Romanian, Italian and other Allied POWs, and the Ilag IV camp for interned civilians from western Allied countries in the region.

[30] There were also 17 subcamps of the Flossenbürg concentration camp, in which both men and women, mostly Polish, Soviet and Jewish, but also French, Yugoslav, Czech, Romani and of several other ethnicities, were imprisoned and subjected to forced labor,[31] and 16 subcamps of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, in which men and women, mostly Polish and Jewish, but also Czechs, Russians, and other people, were similarly imprisoned and subjected to forced labor.

After the war ended in 1945, after initial plans to cede lands to Germany or to create German-speaking cantons had been abandoned,[24] the vast majority of the Bohemian Germans were expelled by order of the reestablished Czechoslovak central government, based on the Potsdam Agreement.

In February 1948, the non-communist members of the government resigned in protest against arbitrary measures by the communists and their Soviet protectors in many of the state's institutions.

In 1989, Agnes of Bohemia became the first saint from a Central European country to be canonized (by Pope John Paul II) before the "Velvet Revolution" later that year.

[37] Petr Pithart, former Czech prime minister and president of the Senate at the time, remained one of the main advocates of the land system,[38] claiming that the primary reason for its refusal was the fear of possible Moravian separatism.

Pressure brought on by the Soviet Union led to a ceasing of military operations, with the Czech minority being expelled to Germany and Czechoslovakia.