Bohemian Reformation

Lasting for more than 200 years, it had a significant impact on the historical development of Central Europe and is considered one of the most important religious, social, intellectual and political movements of the early modern period.

[2] Although it split into many groups, some characteristics were shared by all of them – communion under both kinds, distaste for the wealth and power of the church, emphasis on the Bible preached in a vernacular language and on an immediate relationship between man and God.

The victorious restored King Ferdinand II decided to force every inhabitant of Bohemia and Moravia to become Roman Catholic in accordance with the principle cuius regio, eius religio of the Peace of Augsburg (1555).

[9] Apart from the university theologians there were also reform preachers, such as Conrad Waldhauser (died in 1369), an Austrian Augustinian from a monastery in Waldhausen who preached in the Old Town of Prague in German and Latin especially against simony and low morals.

The Bible was the only reliable authority in all matters of faith for him and only sincere followers of Christ were true Christians in his opinion.

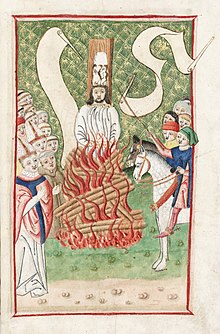

Jan Hus and his friends (e. g. Jacob of Mies) were skeptical about the idea of conciliarism which called for a church reform from above via cardinals and theologians.

[9] Together with Wycliffe they thought that aristocracy could help the church to become poor and focused only on spiritual issues by confiscation of its property.

In 1412, Jan Hus criticized selling indulgences which led to an unrest in Prague suppressed by the city council.

[6] Therefore, he started to write many texts in Czech, such as basics of the Christian faith or preachings, intended mainly for the priests whose knowledge of Latin was poor.

[15] For the Bohemian Reformation, this step was as significant as the 95 theses nailed to the door of the Wittenberg church by Martin Luther in 1517.

[9] In 1414, Jacob of Mies first served the holy communion under both kinds to laymen (which was forbidden by the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215) by the approval of Hus who already dwelt in Constance.

[17] The ideological and political program shared by the Hussites at the beginning of the Hussite Wars was contained in the Four Articles of Prague, which can be summarized as: In the summer of 1419, tens of thousands of people gathered for a massive outdoor religious service on a hill christened Mount Tabor, where the town Tábor was founded.

[19] The text of Compactata based on the Four Articles of Prague was accepted by the Czech (Bohemian and Moravian) political representation as well as by the Council of Basel, but the Pope refused to recognize it.

For a long time, this church – schismatic from the Roman point of view – remained a unique phenomenon in Europe.

During the entire sixteenth century Bohemia and Moravia enjoyed a considerable religious tolerance that was not limited by the principle cuius regio, eius religio.

The joining of the Utraquists with the Brethren and the Lutherans in support of the Bohemian Confession (Confessio Bohemica, 1575) could not but antagonize Rome further.

[20] The main expression of its confessional distinctiveness was a reformed liturgy that combined Latin and Czech, and practiced communion under both kinds for the laity of all ages, including little children as well as infants.

[20] The Unity of the Brethren (Latin: Unitas fratrum, Czech: Jednota bratrská) was founded in 1457 by Bohemian followers of Jan Hus who were disappointed by the religious development in their country, especially by the wars which were led in the name of God.

[6] Considered to be heretics and persecuted by both Roman Catholics and Utraquists (Hussites, Calixtines) they became tolerant to other Christian denominations.

Although the Unity of the Brethren was just a small religious group, its contribution for the development of the Czech monophonic sacred song is indisputable.

In 1722 the Unity of the Brethren was renewed in Saxony by emigrants from Moravia with support of a local count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf.