Bojagi

Bojagi were sometimes embellished to be lined, unlined, padded, quilted, or decorated with painting, paper-thin gold sheets, embroidery, and patchwork.

[4] Within the Joseon royal court the preferred fabric in bojagi construction was domestically produced pink-red to purple cloth.

[2] Unlike the used and re-used frugality of non-royal wrapping cloths, hundreds of new bojagi were commissioned on special occasions such as royal birthdays and New Year's Day.

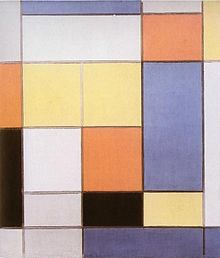

[3] Korean women, taught from an early age to be patient and frugal, would separate small scraps of cloth into different groups according to material, shape, colors, and weight.

This process provided an opportunity for Joseon dynasty women to express their creative talents, with the actual sewing likely similar to sutra copying.

While lightweight cloths helped air to circulate during summer, to keep food warm in winter bojagi could be padded and lined as well.

Embroidered bojagi, also called subo (수보) (the prefix su means embroidery), was another form of decorated cloth.

A common ornament was that of stylized trees, varying in style from 'naive',[10] to detailed depictions of flowers, fruits, birds, dragons, clouds and symbols of good luck.

In addition to being lined and embroidered, the kirogi po were often decorated with strands of rainbow-colored threads representing rice stalks, a symbol of the family's wishes for abundance in married life.

[3] The museum was founded by husband-and-wife duo Dong-hwa Huh (허동화; 1926−2018) and Young-suk Park (박영숙; born 1932) with the aim of preserving Korean embroidery arts and educating the public on its artistic and historical significance.

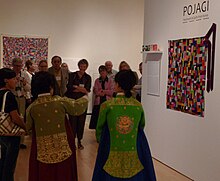

Huh and Park's bojagi collection garnered international attention, with sixty overseas exhibitions displayed in eleven countries.

The patchwork style of the jogak bo have inspired artists working in other media, such as clothing designers Lee Chunghie[16][19] and Karl Lagerfeld.