Book of Daniel

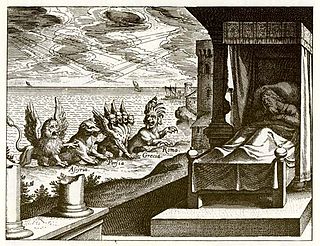

Ostensibly "an account of the activities and visions of Daniel, a noble Jew exiled at Babylon",[1] the text features a prophecy rooted in Jewish history, as well as a portrayal of the end times that is both cosmic in scope and political in its focus.

[Notes 1] Young Israelites of noble and royal family, "without physical defect, and handsome," versed in wisdom and competent to serve in the palace of the king, are taken to Babylon to be taught the literature and language of that nation.

Their overseer fears for his life in case the health of his charges deteriorates, but Daniel suggests a trial and the four emerge healthier than their counterparts from ten days of consuming nothing but vegetables and water.

When their training is done Nebuchadnezzar finds them 'ten times better' than all the wise men in his service and therefore keeps them at his court, where Daniel continues until the first year of King Cyrus.

[14] Daniel's companions Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego refuse to bow to King Nebuchadnezzar's golden statue and are thrown into a fiery furnace.

[16] Belshazzar and his nobles blasphemously drink from sacred Jewish temple vessels, offering praise to inanimate gods, until a mysterious hand suddenly appears and writes upon the wall.

The horrified king summons Daniel, who upbraids him for his lack of humility before God and interprets the message: Belshazzar's kingdom will be given to the Medes and Persians.

He will defeat and subjugate Libya and Egypt, but "reports from the east and north will alarm him," and he will meet his end "between the sea and the holy mountain."

Daniel fails to understand and asks again what will happen, and is told: "From the time that the daily sacrifice is abolished and the abomination that causes desolation is set up, there will be 1,290 days.

[26] The visions of chapters 7–12 reflect the crisis which took place in Judea in 167–164 BC when Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Greek king of the Seleucid Empire, threatened to destroy traditional Jewish worship in Jerusalem.

[30] With the Jewish religion now clearly under threat a resistance movement sprang up, led by the Maccabee brothers, and over the next three years it won sufficient victories over Antiochus to take back and purify the Temple.

[43] Chapter 1 was composed (in Aramaic) at this time as a brief introduction to provide historical context, introduce the characters of the tales, and explain how Daniel and his friends came to Babylon.

[51] "The legendary Daniel, known from long ago but still remembered as an exemplary character ... serves as the principal human 'hero' in the biblical book that now bears his name"; Daniel is the wise and righteous intermediary who is able to interpret dreams and thus convey the will of God to humans, the recipient of visions from on high that are interpreted to him by heavenly intermediaries.

[53] Some evidence of the book's date can be found in the fact that Daniel is not present in the Hebrew Bible's canon of the prophets (where it might arguably be expected to fit), which was closed c. 200 BC.

Additionally, the Wisdom of Sirach, a work dating from c. 180 BC, draws on almost every book of the Old Testament except Daniel, leading scholars to suppose that its author was unaware of it; Daniel is, however, quoted in a section of the Sibylline Oracles commonly dated to the middle of the 2nd century BC, and was popular at Qumran at much the same time, suggesting that it was known from the middle of that century.

Between them, they preserve text from eleven of Daniel's twelve chapters, and the twelfth is quoted in the Florilegium (a compilation scroll) 4Q174, showing that the book at Qumran did not lack this conclusion.

[56] (This section deals with modern scholarly reconstructions of the meaning of Daniel to its original authors and audience) The Book of Daniel is an apocalypse, a literary genre in which a heavenly reality is revealed to a human recipient; such works are characterized by visions, symbolism, an other-worldly mediator, an emphasis on cosmic events, angels and demons, and pseudonymity (false authorship).

[57] The production of apocalypses occurred commonly from 300 BC to 100 AD, not only among Jews and Christians, but also among Greeks, Romans, Persians and Egyptians, and Daniel is a representative apocalyptic seer, the recipient of divine revelation: he has learned the wisdom of the Babylonian magicians and surpassed them because his God is the true source of knowledge; he is one of the maskilim (משכלים), the wise ones, who have the task of teaching righteousness and whose number may be considered to include the authors of the book itself.

[58] The book is also an eschatology, as the divine revelation concerns the end of the present age, a predicted moment in which God will intervene in history to usher in the final kingdom.

[59] It gives no real details of the end-time, but it seems that God's kingdom will be on this earth, that it will be governed by justice and righteousness, and that the tables will be turned on the Seleucids and those Jews who have cooperated with them.

[3] The book is filled with monsters, angels, and numerology, drawn from a wide range of sources, both biblical and non-biblical, that would have had meaning in the context of 2nd-century Jewish culture and while Christian interpreters have always viewed these as predicting events in the New Testament—"the Son of God", "the Son of Man", Christ and the Antichrist—the book's intended audience is the Jews of the 2nd century BC.

"[76] According to Daniel R. Schwartz, without the claim of the resurrection of Jesus, Christianity would have disappeared like the movements following other charismatic Jewish figures of the 1st century.

[78] Moments of national and cultural crisis continually reawakened the apocalyptic spirit, through the Montanists of the 2nd/3rd centuries, persecuted for their millennialism, to the more extreme elements of the 16th-century Reformation such as the Zwickau prophets and the Münster Rebellion.

[79] For modern popularizers, the visions and revelations of Daniel remain a guide to the future, when the Antichrist will be destroyed by Jesus Christ at the Second Coming.

[81] Isaac Newton paid special attention to it, Francis Bacon borrowed a motto from it for his work Novum Organum, Baruch Spinoza drew on it, its apocalyptic second half attracted the attention of Carl Jung, and it inspired musicians from medieval liturgical drama to Darius Milhaud and artists including Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Eugène Delacroix.