Lebor Gabála Érenn

The Lebor Gabála was highly influential[2] and was largely "accepted as conventional history by poets and scholars down until the 19th century".

[4] It appears to be mostly based on medieval Christian pseudo-histories,[4] but it also incorporates some of Ireland's native pagan mythology.

[5] Scholars believe that the goal of its writers was to provide a history for Ireland that could compare to that of Rome or Israel, and which was compatible with Christian teaching.

The writers of Lebor Gabála Érenn sought to create an epic written history of the Irish comparable to that of the Israelites in the Old Testament of the Bible.

The writers also sought to incorporate native pre-Christian stories about the origins of the Irish, and to reconcile them with medieval Christian lore.

One of the poems in LGE, for instance, recounts how goddesses from among the Tuatha Dé Danann took husbands from the Gaeil when they 'invaded' and 'colonised' Ireland.

The pattern of successive invasions recounted in the LGE is reminiscent of Timagenes of Alexandria's account of the origins of the Gauls of continental Europe.

Cited by the 4th-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus, Timagenes (1st century BC) describes how the ancestors of the Gauls were driven from their native lands in eastern Europe by a succession of wars and floods.

In his Lectures on the Manuscript Materials of Ancient Irish History (1861), Eugene O'Curry, Professor of Irish History and Archaeology at the Catholic University of Ireland, discussed various genres of historical tales mentioned in the manuscripts: The Tochomladh was an Immigration or arrival of a Colony; and under this name the coming of the several colonies of Parthalon of Nemedh, of the Firbolgs, the Tuatha Dé Danann, the Milesians, etc., into Erinn, are all described in separate tales.

Macalister theorised that the quasi-Biblical text had been a scholarly Latin work named Liber Occupationis Hiberniae ("The Book of the Taking of Ireland").

The earliest surviving account of Irish origins is found in the Historia Brittonum ("History of the Britons"), written in Wales in the 9th century.

Most of the poems on which the 11th–12th century version of LGE was based were written by the following four poets: It was late in the 11th century that a single anonymous scholar appears to have brought together these and numerous other poems and fitted them into an elaborate prose framework – partly of his own composition and partly drawn from older, no longer extant sources (i.e. the tochomlaidh referred to above by O'Curry), paraphrasing and enlarging the verse.

[7] The collection can be divided into ten chapters: A retelling of the familiar Christian story of the creation, the fall of Man and the early history of the world.

After some time they leave Scythia and spend 440 years travelling the Earth, undergoing trials and tribulations akin to those of the Israelites.

There, Goídel's descendant Breogán founds a city called Brigantia, and builds a tower from the top of which his son Íth glimpses Ireland.

According to the Lebor Gabála, the first people to arrive in Ireland are led by Cessair, daughter of Bith, son of Noah.

Named figures are credited with introducing cattle husbandry, ploughing, cooking, brewing, and dividing the island in four.

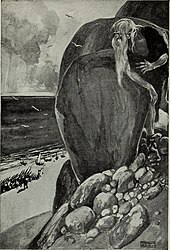

[25][26] The Fomorians have been interpreted as a group of deities who represent the harmful or destructive powers of nature; personifications of chaos, darkness, death, blight and drought.

During their time in Ireland, the Nemedians clear twelve plains and build two royal forts, and four lakes burst from the ground.

This tribute that the Nemedians are forced to pay may be "a dim memory of sacrifice offered at the beginning of winter, when the powers of darkness and blight are in the ascendant".

In some versions, the Fir Bolg flee Ireland and settle on remote offshore islands, while in others they are granted the province of Connacht.

[31] After seven years, Dian Cecht the physician and Credne the metalsmith replace Nuada's hand/arm with a working silver one, and he re-takes the kingship.

The Gaels agree, but once their ships are nine waves from Ireland, the Tuath Dé conjure up a great wind that prevents them from sailing back to land.

A continuation of the previous chapter, it is the most accurate part of Lebor Gabála, being concerned with historical kings of Ireland whose deeds and dates are preserved in contemporary written records.

As late as the 17th century, Geoffrey Keating drew on it while writing his history of Ireland, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, and it was also used extensively by the authors of the Annals of the Four Masters.

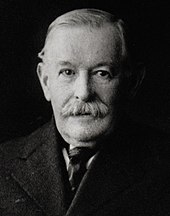

[33] The Irish archaeologist R. A. Stewart Macalister, who translated the work into English, wrote: "There is not a single element of genuine historical detail, in the strict sense of the word, anywhere in the whole compilation".

[39] The claim that the Gaels settled in the Maeotian marshes seems to have been taken from the Book of the History of the Franks,[40] and their travels to Crete and Sicily may have been based on the tale of Aeneas.

[43] While most scholars view the work as primarily myth rather than history, some have argued that it is loosely based on real events.

[45][46] In The White Goddess (1948), British poet and mythologist Robert Graves argued that myths brought to Ireland centuries before the introduction of writing were preserved and transmitted accurately by word of mouth before being written down in the Christian Era.

Taking issue with Macalister, with whom he corresponded on this and other matters, he declared some of the Lebor Gabála's traditions "archaeologically plausible".