Kingdom of Munster

It claims that the name partly derives from Eochaidh Mumu, one of the early Heberian High Kings of Ireland who ruled the area.

[3] This High King held the royal nickname mó-mó meaning "greater-greater", because he was supposed to be more powerful and greater in stature than any other Irishman of his time (the Annals of the Four Masters claims he reigned from 1449–1428 BC).

[3] The early Kings of Munster, derived from the Érainn (one of the major sub-branches of Gaels in Ireland), were mentioned in the Red Branch Cycle of Irish traditional history.

These men are all presented as great warriors, in particular Cú Roí features in the Táin bó Cúailnge, where he fights Amergin mac Eccit, until requested to stop by Meadhbh.

There was also a Temair Luachra ("Tara of the Rushes"), existing as the royal site of Munster, but this is lost to history (it is potentially synonymous with Caherconree).

According to the Book of Glendalough, a member of the Munster royal family, Fíatach Finn, moved north and became King of Ulster, establishing the Érainn kindred known as the Dál Fiatach.

His mother was Sadb ingen Chuinn from the Connachta and he was called Mac Con ("Son of the Hound") because he was supposedly suckled by his foster-father Ailill Aulom's greyhound.

He ascended to the High Kingship from his Munster base after killing Art mac Cuinn in the Battle of Maigh Mucruimhe, which is the subject of a literary tale.

Many of the earliest saints of Ireland mentioned in the Codex Salmanticensis had strong Munster connections, particularly St. Ailbe in Emly, historical location of the Mairtine.

The conversion of the Eóganacht Chaisil, who were Kings of Cashel and gaining more and more influence in Munster, to the detriment of the Corcu Loígde, occurred during the reign of Óengus mac Nad Froích.

[5] Indeed, the very finding of Cashel, which was originally in the land of the Éile and its establishment as the base of the Eóganachta is attributed in the texts Acallam na Senórach and Senchas Fagbála Caisil to a miraculous "vision" of St. Patrick, sixty years beforehand by Corc mac Luigthig.

According to the Acallam, Óengus then levied a tri-annual tribute in Munster known as the "scruple of Patrick’s baptism", showing a clear political interest (this was exacted until the times of St. Cormac mac Cuilennáin).

These monks often chose isolated and harsh locations for their monasteries, exhibiting an ascetic spirituality, similar to that of the Desert Fathers in Christian Egypt.

Under Faílbe Flann mac Áedo Duib, Munster crossed the River Shannon and defeated the Ui Fiachrach Aidhne of Connacht, taking from them what would become Thomond (or in much later times County Clare) and settling it with Déisi.

Despite the size of their kingdom, Munster was usually substantially weaker than the northern Uí Néill powerhouse; the Eóganachta built up a propaganda that they ruled through "prosperity and generosity", rather than just brute force.

[9] The raiders chose these monasteries primarily because they were isolated and easy to attack from the Sea; they took provisions, precious goods (metalwork especially), livestock and human captives (these people were either ransomed back if they were high-profile clerics or forced into slavery abroad).

[10] In some cases in Ireland, by the mid-9th century, the Vikings set up coastal encampments known as longphorts; specifically in relation to Munster, this included; Waterford, Youghal, Cork and Limerick.

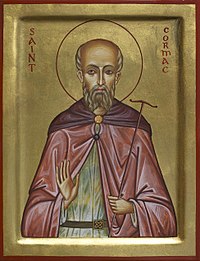

The ascent of elements outside of the main royal families occurred, for instance; St. Cormac mac Cuilennáin from a very much junior branch of the Eóganacht Chaisil became King of Munster during the early 10th century.

Cormac and his right-hand man Flaithbertach mac Inmainén were able to inflict defeats on High King Flann Sinna after the latter had ravaged Munster in 906.

As well as his martial prowess and religious piety, Cormac was known for his literacy, as his name appears on the Sanas Cormaic, an Irish language glossary.

During the reign of Muirchertach, his grandfather Brian's feats were portrayed in the literary work Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib in a proto-Irish nationalist sense as a Gaelic war of liberation against the Viking invaders and their collaborators.

[citation needed] Towards the end of Muirchertach's reign, he fell ill. His brother Diarmaid Ó Briain who was powerful in Waterford (and had earlier been banished to Deheubarth in Britain), felt that he would make a better ruler.