Genetic history of the British Isles

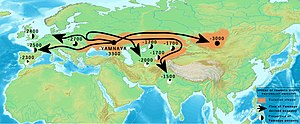

[1] One of the lasting proposals of this study with regards to Europe is that within most of the continent the majority of genetic diversity may best be explained by immigration coming from the southeast towards the northwest or in other words from the Middle East towards Britain and Ireland.

[5] Stephen Oppenheimer and Bryan Sykes, meanwhile, claimed that the majority of the DNA in the British Isles had originated from a prehistoric migration from the Iberian peninsula and that subsequent invasions had had little genetic input.

[6][7] In the last decade, improved technologies for extracting ancient DNA have allowed researchers to study the genetic impacts of these migrations in more detail.

This led to Oppenheimer and Sykes' conclusions about the origins of the British being seriously challenged, since later research demonstrated that the majority of the DNA of much of continental Europe, including Britain and Ireland, is ultimately derived from Steppe invaders from the east rather than Iberia.

This suggests that farming was brought to the British Isles by sea from north-west mainland Europe, by a population that was, or became in succeeding generations, relatively large.

[18] Patterson et al. (2021) believes that these migrants were "genetically most similar to ancient individuals from France" and had higher levels of Early European Farmers (EEF) ancestry.

[22] Cassidy et al. (2025) propose that gene flow across the Channel throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages is a plausible scenario for the introduction of Celtic languages to Britain.

They found evidence for a significant increase in EEF ancestry in Middle-to-Late Iron Age individuals from Southern Britain, indicating substantial population movements across the channel during this period.

This study concluded that modern southern, central and eastern English populations were of "a predominantly Anglo-Saxon-like ancestry" whilst those from northern and southwestern England had a greater degree of indigenous origin.

The authors also noted that while a large proportion of the ancestry of the present-day English derives from the Anglo-Saxon migration event, it has been diluted by later migration from a population source similar to that of Iron Age France, Belgium and western Germany, which probably "resulted from pulses of immigration or continuous gene flow between eastern England and its neighbouring regions", but which entered northern and eastern England after the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons.

[25] The post-Roman period saw a significant alteration in the genetic makeup of southern Britain due to the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons; however, historical evidence suggests that Wales was little affected by these migrations.

A study published in 2016 compared samples from modern Britain and Ireland with DNA found in skeletons from Iron Age, Roman and Anglo-Saxon era Yorkshire.

The study found that most of the Iron Age and Roman era Britons showed strong similarities with both each other and modern-day Welsh populations, while modern southern and eastern English groups were closer to a later Anglo-Saxon burial.

[27] A third study, published in 2020 and based on Viking era data from across Europe, suggested that the Welsh trace, on average, 58% of their ancestry to the Brythonic people, up to 22% from a Danish-like source interpreted as largely representing the Anglo-Saxons, 3% from Norwegian Vikings, and 13% from further south in Europe such as Italy, to a lesser extent, Spain and can possibly be related to French immigration during the Norman period.

[29] A study of a diverse sample of 2,039 individuals from the United Kingdom allowed the creation of a genetic map and the suggestion that there was a substantial migration of peoples from Europe prior to Roman times forming a strong ancestral component across England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, but which had little impact in Wales.

[30] Speaking of these results, Professor Peter Donnelly, of the University of Oxford, said that the Welsh carry DNA which could be the most ancient in UK and that people from Wales are genetically relatively distinct.

[31] Historical and toponymic evidence suggests a substantial Viking migration to many parts of northern Britain; however, particularly in the case of the Danish settlers, differentiating their genetic contribution to modern populations from that of the Anglo-Saxons has posed difficulties.

[28] A 2015 study using data from the Neolithic and Bronze Ages showed a considerable genetic difference between individuals during the two periods, which was interpreted as being the result of a migration from the Pontic steppes.

"[32] Another study, using modern autosomal data, found a large degree of genetic similarity between populations from northeastern Ireland, southern Scotland and Cumbria.

In general, hunter-gatherer ancestries like WHG increase the likelihood of darker skin and hair, Alzheimer's disease and traits related to cholesterol, blood pressure and diabetes among British people.

One common R1b subclade in Britain is R1b-U106, which reaches its highest frequencies in North Sea areas such as southern and eastern England, the Netherlands and Denmark.

[39] It was also present among Celtic Britons in eastern England prior to the Anglo-Saxon and Viking invasions, as well as Roman soldiers in York who were of native descent.

Within Britain, the most common subclade is I1, which also occurs frequently in northwestern continental Europe and southern Scandinavia, and has thus been associated with the settlement of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings.

The genetics of some visibly white (European) people in England suggests that they are "descended from north African, Middle Eastern and Roman clans".