Bootleg recording

Bootlegs reached new popularity with Bob Dylan's Great White Wonder, a compilation of studio outtakes and demos released in 1969 using low-priority pressing plants.

[7] Other bootlegs may be soundboard recordings taken directly from a multi-track mixing console used to feed the public address system at a live performance.

[9] Some bootlegs consist of private or professional studio recordings distributed without the artist's involvement, including demos, works-in-progress or discarded material.

Strictly speaking, these were unlicensed recordings, but, because the work required to clear all the copyrights and publishing of every track for an official release was considered to be prohibitively expensive, the bootlegs became popular.

[11] According to the enthusiast and author Clinton Heylin, the concept of a bootleg record can be traced back to the days of William Shakespeare, when unofficial transcripts of his plays would be published.

One example was a bootleg of Judy Garland performing Annie Get Your Gun (1950), before Betty Hutton replaced her early in production, but after a full soundtrack had been recorded.

[17] The first popular rock music bootleg resulted from Bob Dylan's activities between largely disappearing from the public eye after his motorcycle accident in 1966, and the release of John Wesley Harding at the end of 1967.

Through various contacts in the radio industry, a number of pioneering bootleggers managed to buy a reel-to-reel tape containing a selection of unreleased Dylan songs intended for distribution to music publishers and wondered if it would be possible to manufacture them on an LP.

[23] The large followings of rock artists created a lucrative market for the mass production of unofficial recordings on vinyl, as it became evident that more and more fans were willing to purchase them.

[24] In addition, the huge crowds which turned up to these concerts made the effective policing of the audience for the presence of covert recording equipment difficult.

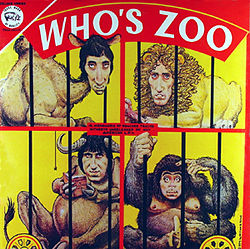

[26] Some bootleggers noticed rock fans that had grown up with the music in the 1960s wanted rare or unreleased recordings of bands that had split up and looked unlikely to reform.

It provided the true information on bootlegs with fictitious labels, and included details on artists and track listings, as well as the source and sound quality of the various recordings.

[34] The pioneering bootlegger Rubber Dubber sent copies of his bootleg recordings of live performances to magazines such as Rolling Stone in an attempt to get them reviewed.

It received a good review from Sounds' Chas de Whalley, who said it was an album "no self-respecting rock fan would turn his nose up" at.

[37] The 1980s saw the increased use of audio cassettes and videotapes for the dissemination of bootleg recordings, as the affordability of private dubbing equipment made the production of multiple copies significantly easier.

[39] For a while, stalls at major music gatherings such as the Glastonbury Festival sold mass copies of bootleg soundboard recordings of bands who, in many cases, had played only a matter of hours beforehand.

However, officials soon began to counteract this illegal activity by making raids on the stalls and, by the end of the 1980s, the number of festival bootlegs had consequently dwindled.

[43] Following the success of Ultra Rare Trax, the 1990s saw an increased production of bootleg CDs, including reissues of shows that had been recorded decades previously.

In particular, companies in Germany and Italy exploited the more relaxed copyright laws in those countries by pressing large numbers of CDs and including catalogs of other titles on the inlays, making it easier for fans to find and order shows direct.

[36] Physical bootlegging largely shifted to countries with laxer copyright laws, with the results distributed through existing underground channels, open-market sites such as eBay, and other specialised websites.

[50] Artists had a mixed reaction to online bootleg sharing; Bob Dylan allowed fans to download archive recordings from his official website, while King Crimson's Robert Fripp and Metallica were strongly critical of the ease with which Napster circumvented traditional channels of royalty payments.

YouTube's owner, Google, believes that under the "safe-harbor" provision of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), it cannot be held responsible for content, allowing bootleg media to be hosted on it without fear of a lawsuit.

[52] An audience recording of one of David Bowie's last concerts before he retired from touring in 2004 was uploaded to YouTube and received a positive review in Rolling Stone.

[53] Bilal's unreleased second album, Love for Sale, leaked in 2006 and became one of the most infamously bootlegged recordings during the digital piracy era,[54] with its songs since remaining on YouTube.

[62][63] In 2007, Judge Baer's ruling was overruled, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found that the anti-bootlegging statute was within the power of Congress.

[68] They were unique among bands in that their live shows tended not to be pressed and packaged as LPs, but remained in tape form to be shared between tapers.

[69] The group were strongly opposed to commercial bootlegging and policed stores that sold them, while the saturation of tapes among fans suppressed any demand for product.

[70] In 1985, the Grateful Dead, after years of tolerance, officially endorsed live taping of their shows, and set up dedicated areas that they believed gave the best sound recording quality.

[75] DGM's reverse engineering of the distribution-networks for bootlegs helped it to make a successful transition to an age of digital distribution, "unique" (in 2009) among music labels.

[78] According to a 2012 report in Rolling Stone, many artists have now concluded that the volume of bootlegged performances on YouTube in particular is so large that it is counterproductive to enforce it, and they should use it as a marketing tool instead.