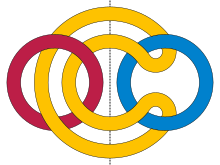

Borromean rings

In mathematics, the Borromean rings[a] are three simple closed curves in three-dimensional space that are topologically linked and cannot be separated from each other, but that break apart into two unknotted and unlinked loops when any one of the three is cut or removed.

In knot theory, the Borromean rings can be proved to be linked by counting their Fox n-colorings.

In arithmetic topology, certain triples of prime numbers have analogous linking properties to the Borromean rings.

The commonly-used diagram for the Borromean rings consists of three equal circles centered at the points of an equilateral triangle, close enough together that their interiors have a common intersection (such as in a Venn diagram or the three circles used to define the Reuleaux triangle).

[11] The Ōmiwa Shrine in Japan is also decorated with a motif of the Borromean rings, in their conventional circular form.

[3] A 13th-century French manuscript depicting the Borromean rings labeled as unity in trinity was lost in a fire in the 1940s, but reproduced in an 1843 book by Adolphe Napoléon Didron.

The number of colorings meeting these conditions is a knot invariant, independent of the diagram chosen for the link.

[4] More generally Michael H. Freedman and Richard Skora (1987) proved using four-dimensional hyperbolic geometry that no Brunnian link can be exactly circular.

A realization of the Borromean rings by three mutually perpendicular golden rectangles can be found within a regular icosahedron by connecting three opposite pairs of its edges.

[2] Every three unknotted polygons in Euclidean space may be combined, after a suitable scaling transformation, to form the Borromean rings.

[29] More generally, Matthew Cook has conjectured that any three unknotted simple closed curves in space, not all circles, can be combined without scaling to form the Borromean rings.

After Jason Cantarella suggested a possible counterexample, Hugh Nelson Howards weakened the conjecture to apply to any three planar curves that are not all circles.

Mathematically, such a realization can be described by a smooth curve whose radius-one tubular neighborhood avoids self-intersections.

The minimum ropelength of the Borromean rings has not been proven, but the smallest value that has been attained is realized by three copies of a 2-lobed planar curve.

[2][30] Although it resembles an earlier candidate for minimum ropelength, constructed from four circular arcs of radius two,[31] it is slightly modified from that shape, and is composed from 42 smooth pieces defined by elliptic integrals, making it shorter by a fraction of a percent than the piecewise-circular realization.

[2][30] For a discrete analogue of ropelength, the shortest representation using only edges of the integer lattice, the minimum length for the Borromean rings is exactly

[36] The complement of the Borromean rings is universal, in the sense that every closed 3-manifold is a branched cover over this space.

[39] A monkey's fist knot is essentially a 3-dimensional representation of the Borromean rings, albeit with three layers, in most cases.

In 1997, biologist Chengde Mao and coworkers of New York University succeeded in constructing a set of rings from DNA.

[44] In 2003, chemist Fraser Stoddart and coworkers at UCLA utilised coordination chemistry to construct a set of rings in one step from 18 components.

[40] Borromean ring structures have been used to describe noble metal clusters shielded by a surface layer of thiolate ligands.

[45] A library of Borromean networks has been synthesized by design by Giuseppe Resnati and coworkers via halogen bond driven self-assembly.

[46] In order to access the molecular Borromean ring consisting of three unequal cycles a step-by-step synthesis was proposed by Jay S. Siegel and coworkers.

The existence of such states was predicted by physicist Vitaly Efimov in 1970, and confirmed by multiple experiments beginning in 2006.

[50] Another analog of the Borromean rings in quantum information theory involves the entanglement of three qubits in the Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger state.