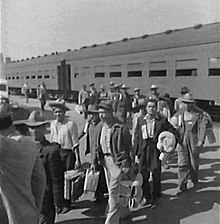

Bracero Program

The program, which was designed to fill agriculture shortages during World War II, offered employment contracts to 5 million braceros in 24 U.S. states.

L. 82–78), enacted as an amendment to the Agricultural Act of 1949 by the United States Congress,[4] which set the official parameters for the Bracero Program until its termination in 1964.

In Texas, the program was banned by Mexico for several years during the mid-1940s due to the discrimination and maltreatment of Mexicans, which included lynchings along the border.

Consequently, several years of the short-term agreement led to an increase in undocumented immigration and a growing preference for operating outside of the parameters set by the program.

Railroad work contracts helped the war effort by replacing conscripted farmworkers, staying in effect until 1945 and employing about 100,000 men.

The dilemma of short handed crews prompted the railway company to ask the government permission to have workers come in from Mexico.

Bracero railroaders were also in understanding of an agreement between the U.S. and Mexico to pay a living wage, and provide adequate food, housing, and transportation.

Oftentimes, just like agricultural braceros, the railroaders were subject to rigged wages, harsh or inadequate living spaces, food scarcity, and racial discrimination [citation needed].

Thus, during negotiations in 1948 over a new bracero program, Mexico sought to have the United States impose sanctions on American employers of undocumented workers.

There were a number of hearings about the United States–Mexico migration, which overheard complaints about Public Law 78 and how it did not adequately provide them with a reliable supply of workers.

In 1955, the AFL and CIO spokesman testified before a Congressional committee against the program, citing lack of enforcement of pay standards by the Labor Department.

The aforesaid males of Japanese and or Mexican extraction are expressly forbidden to enter at any time any portion of the residential district of said city under penalty of law.

A letter from Howard A. Preston describes payroll issues that many braceros faced, "The difficulty lay chiefly in the customary method of computing earnings on a piecework basis after a job was completed.

In a newspaper article titled "U.S. Investigates Bracero Program", published by The New York Times on January 21, 1963, claims the U.S. Department of Labor was checking false-record keeping.

In this short article the writer explains, "It was understood that five or six prominent growers have been under scrutiny by both regional and national officials of the department.

One key difference between the Northwest and braceros in the Southwest or other parts of the United States involved the lack of Mexican government labor inspectors.

[61] Lack of food, poor living conditions, discrimination, and exploitation led braceros to become active in strikes and to successfully negotiate their terms.

These letters went through the US postal system and originally they were inspected before being posted for anything written by the men indicating any complaints about unfair working conditions.

[63] Permanent settlement of bracero families was feared by the US, as the program was originally designed as a temporary work force which would be sent back to Mexico eventually.

The end of the Bracero Program in 1964 was followed by the rise to prominence of the United Farm Workers (UFW) and the subsequent transformation of American migrant labor under the leadership of César Chávez, Gilbert Padilla, and Dolores Huerta.

Newly formed labor unions (sponsored by Chávez and Huerta), namely the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, were responsible for series of public demonstrations including the Delano grape strike.

These efforts demanded change for labor rights, wages and the general mistreatment of workers that had gained national attention with the Bracero Program.

Mexican employers and local officials feared labor shortages, especially in the states of west-central Mexico that traditionally sent the majority of migrants north (Jalisco, Guanajuato, Michoacan, Zacatecas).

The Catholic Church warned that emigration would break families apart and expose braceros to Protestant missionaries and to labor camps where drinking, gambling, and prostitution flourished.

Social scientists doing field work in rural Mexico at the time observed these positive economic and cultural effects of bracero migration.

A 1980 Congressional Research Service report found that the Bracero Program was "instrumental" in significantly reducing illegal immigration by the mid-1950s.

A key victory for these former braceros was the abolition of the short-handed hoe, el cortito, spurred by the efforts of American lawyer Maurice Jordan.

Jordan was successfully able to win a case against California growers, claiming that the tool did not increase crop yield and caused several health issues for workers.

[82] A 2018 study published in the American Economic Review found that the Bracero program did not have any adverse impact on the labor market outcomes of American-born farm workers.

[6] In October 2009, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History opened a bilingual exhibition titled, "Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program, 1942–1964."