Ogallala Aquifer

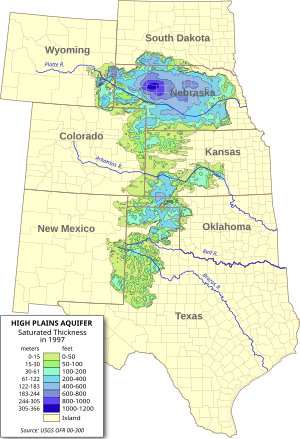

As one of the world's largest aquifers, it underlies an area of approximately 174,000 sq mi (450,000 km2) in portions of eight states (South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas).

[2][3] Large-scale extraction for agricultural purposes started after World War II due partially to center pivot irrigation and to the adaptation of automotive engines to power groundwater wells.

[6] The aquifer system supplies drinking water to 82% of the 2.3 million people (1990 census) who live within the boundaries of the High Plains study area.

[7] The deposition of aquifer material dates back two to six million years, from the late Miocene to early Pliocene ages when the southern Rocky Mountains were still tectonically active.

Erosion of the Rockies provided alluvial and aeolian sediment that filled the ancient channels and eventually covered the entire area of the present-day aquifer, forming the water-bearing Ogallala Formation.

An impervious geological layer between the aquifer and surface of the land, combined with an arid climate, prevents much recharge from occurring.

Nitrate levels generally meet USGS water quality standards, but continue to gradually increase over time.

Since major groundwater pumping began in the late 1940s, overdraft from the High Plains Aquifer has amounted to 332,000,000 acre-feet (410 km3), 85% of the volume of Lake Erie.

[14] Many farmers in the Texas High Plains, which rely particularly on groundwater, are now turning away from irrigated agriculture as pumping costs have risen and as they have become aware of the hazards of overpumping.

The success of large-scale farming in areas that do not have adequate precipitation and do not always have perennial surface water for diversion has depended heavily on pumping groundwater for irrigation.

Early settlers of the semiarid High Plains were plagued by crop failures due to cycles of drought, culminating in the disastrous Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

The center-pivot irrigator was described as the "villain"[21] in a 2013 New York Times article, "Wells Dry, Fertile Plains Turn to Dust" recounting the relentless decline of parts of the Ogallala Aquifer.

Sixty years of intensive farming using huge center-pivot irrigators has emptied parts of the High Plains Aquifer.

[24] In the United States, the biggest users of water from aquifers include agricultural irrigation and oil and coal extraction.

[25] "Cumulative total groundwater depletion in the United States accelerated in the late 1940s and continued at an almost steady linear rate through the end of the century.

[29] During the 1990s, the aquifer held some three billion acre-feet of groundwater used for crop irrigation as well as drinking water in urban areas.

Continued long-term use of the aquifer is "troublesome and in need of major reevaluation," according to the historian Paul H. Carlson, professor-emeritus from Texas Tech University in Lubbock.

[40] As the lead agency in the transboundary pipeline project, the U.S. State Department commissioned an environmental-impact assessment as required by the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969.

The February 2012 report of that investigation states no conflict of interest existed either in the selection of the contractor or in the preparation of the environmental impact statement.

[43] U.S. President Barack Obama "initially rejected the Keystone XL pipeline in January 2012, saying he wanted more time for an environmental review.

[44] In January 2014, the U.S. State Department released its Keystone pipeline Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement for the Keystone XL Project Executive Summary, which concluded that, according to models, a large crude oil spill from the pipeline that reached the Ogallala could spread as far as 1,214 feet (370 m), with dissolved components spreading as much as 1,050 ft (320 m) further.

[46] On January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden signed an executive order[47] to revoke the permit[48] that was granted to TC Energy Corporation for the Keystone XL Pipeline (Phase 4).

Participating farmers grow corn with just over half of the water that they would normally require to irrigate the fields, or they plant several weeks later than customary.