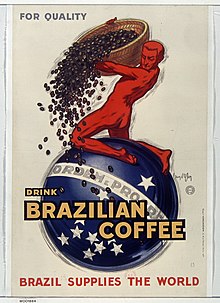

Brazilian coffee cycle

The center-south region of the country was chosen for the plantations because it offered the most appropriate weather conditions and the most suitable soil, according to the needs of the coffee plant.

[3] This return to agriculture occurred mainly for the following reasons: The end of the gold cycle also generated an economic crisis, during which the purchasing power of the population was much lower than during the golden age of mining.

It was a long crisis, which would only end in the following century, during the regency period, with the rise of coffee, which would take the place of gold as the main product of the Brazilian economy.

[1] The coffee culture was far behind that of sugar and cotton and, besides this, the product did not have great importance in world markets and was difficult to plant.

[7] However, there are a few reasons why it has become advantageous to grow coffee:[7][1] In breaking away from Portugal and claiming independence, Brazil ended up tying themselves to the will of Great Britain.

Brazil owed Great Britain a considerable sum of money for a loan to pay off Portugal's compensation for loss of colony.

[8] Great Britain used the debt they were owed to accelerate the end of slavery in Brazil, hijacking slave ships entering the area.

[8] Joining British trading groups was a very appetizing opportunity for Brazilian farmers and merchants, since it was much lower risk and much higher reward than doing it themselves.

[1] But the first great scenario of coffee farming was the Paraíba River Valley (between Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo).

[1][9] After the soil was worn down, the coffee moved inland, crossing the Serra do Mar and Mantiqueira mountains, penetrating the west of São Paulo province, where it found the plateau of purple latosol resulting from the decomposition of basaltic rocks of volcanic origin – the best soil for coffee.

Unlike the Paraíba river valley, there were large plateaus in São Paulo, over which huge cultivated areas were spread.

For some time, producers could rely on internal trafficking, diverting slaves from the impoverished regions of the north to the more prosperous south.

But the constant increase in production required a growing labor force, and alternatives had to be found to solve the shortage of workers.

By 1847, senator Nicolau Vergueiro had brought European settlers to his farms through the so-called "partnership", or "half" system.

[14] These immigrants at the beginning of the Republic were now brought from their countries of origin with official aid, and found sufficient support for their definitive settlement.

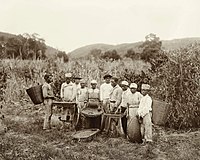

Modern machines, such as pulpers, fans and separators, performed alone the task that previously required the work of up to ninety slaves.

Slaves were being moved where demand was higher, and this meant transferring from small and medium sized farms to the large plantations, making the rich even richer.

[18] With more and more restrictions on slavery over the years, there was a gradual decrease in the number of slaves, which slowly began to affect the productivity and sustainability of the coffee cycle, forcing plantation owners to find other sources of labor.

[22] The overproduction caused by the "ocean" of coffee started a long process of decline in the cycle, which would last for several more decades.

[24] This state intervention all for the benefits of a class of rural producers increased the concentration of income in the country[25] and delayed the development of other sectors, such as industry, in addition to postponing the end of the coffee cycle, which would only occur with the Revolution of 1930.

[27] Coffee was so important in the national economy, and its crisis was so severe, that when asked who would lead the revolution against President Washington Luís, João Neves da Fontoura replied: "General Café".

Even with the end of the cycle, coffee did not disappear overnight; the plant continued to play an important role in the country's economic scenario.

This traffic took place between the Northeast, where sugar cane plantations were in decay, and the coffee producing regions in the Southeast, especially the Paraíba Valley.

[43] The master of the plantation had caught wind of the planned uprising and gathered a small group of forces to quell the rebellion.

The entire court would unite against the slaves, and masters could launch accusations of witchcraft, which was regarded as significant evidence against the revolutionaries.

The coffee cycle set the stage for a number of conflicts between slaves and masters, no doubt accelerating the laws regarding slavery in Brazil.

The plantations gave an enormous boost to the creation of a railroad network capable of transporting the product to the ports of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

In 1854, the first railroad in Brazil was built on the initiative of the then Baron of Mauá, connecting the Estrela beach in Rio to the mountains of Petrópolis.

The coffee cycle facilitated the access of British goods and capital to the Brazilian economy through political and economic pressure from England on Brazil.

[31] Rubber also had a period of prosperity, at the end of the 19th century, causing a surge of progress in Amazonas and bringing many northeasterners to that region.