Military dictatorship in Brazil

While combating the "hardliners" inside the government and supporting a redemocratization policy, Figueiredo could not control the crumbling economy, chronic inflation and concurrent fall of other military dictatorships in South America.

[13] In 2014, nearly 30 years after the regime collapsed, the Brazilian military recognized for the first time the excesses committed by its agents during the dictatorship, including the torture and murder of political dissidents.

[16] While some human rights activists and others assert that the true figure could be much higher, and should include thousands of indigenous people who died because of the regime's negligence,[17][18][19] the armed forces have always disputed this.

Vargas' dictatorship and the presidencies of his democratic successors marked different stages of Brazilian populism (1930–1964), an era of economic nationalism, state-guided modernization, and import substitution trade policies.

Tensions escalated again in the 1950s, as important military circles (the "hard-liners", old positivists whose origins could be traced back to the Brazilian Integralist Action and the Estado Novo) joined the elite and middle classes, and right-wing activists in attempts to prevent presidents Juscelino Kubitschek and João Goulart from taking office due to their supposed support for Communism.

While Kubitschek proved to be friendly to capitalist institutions, Goulart promised far-reaching reforms, expropriated business interests, and promoted economical-political neutrality with the United States.

Influential politicians, such as Carlos Lacerda and even Kubitschek, media moguls (Roberto Marinho, Octávio Frias, Júlio de Mesquita Filho), the Church, landowners, businessmen, and the middle class called for a coup d'état by the Armed Forces to remove the government.

On 1 April 1964, after a night of conspiracy, rebel troops led by general Olímpio Mourão Filho made their way to Rio de Janeiro, considered a legalist bastion.

In order to prevent a civil war and knowing that the United States would openly support the rebels, Goulart fled to Rio Grande do Sul, and then went to exile in Uruguay, where his family owned large estates.

American mass media outlets such as Henry Luce's Time magazine also gave positive remarks about the dissolution of political parties and salary controls at the beginning of Castelo Branco's term.

[31] ...the big press and other institutions made a strong discursive dam in favour of the fall of Goulart, in which they mobilized to exhaustion the theme of red danger (communists) to increase the climate of panic.

The act granted the president the authority to remove elected officials, dismiss civil servants, and revoke for 10 years the political rights of those found guilty of subversion or misuse of public funds.

[34] On 11 April 1964, Congress elected the Army Chief of Staff, marshal Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco as president for the remainder of Goulart's term.

This gave him the latitude to repress the populist left but also provided the subsequent governments of Artur da Costa e Silva (1967–69) and Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1969–74) with a "legal" basis for their hard-line authoritarian rule.

Everything in Brazil is free — but controlled.Through the Institutional Acts, Castelo Branco gave the executive the unchecked ability to change the constitution and remove anyone from office as well as to have the president elected by Congress.

A two-party system was created: the ruling government-backed National Renewal Alliance (ARENA) and the mild not-leftist opposition Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB) party.

[56] The Higher Counsel of Censorship was overseen by the Ministry of Justice, which was in charge of analysing and revising decisions put forward by the director of the Federal Police department.

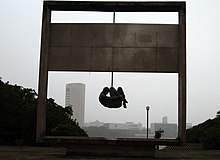

[58] As early as 1964, the military government was already using the various forms of torture it devised systematically not only to gain information it used to crush opposition groups, but also to intimidate and silence any further potential opponents.

[64] Despite the dictatorship's fall, no individual has been punished for the human rights violations, due to the 1979 Amnesty Law written by the members of the government who stayed in place during the transition to democracy.

[66] According to the Comissão de Direitos Humanos e Assistência Jurídica da Ordem dos Advogados do Brasil, the "Brazilian death toll from government torture, assassination and 'disappearances' for 1964–81 was [...] 333, which included 67 killed in the Araguaia guerrilla front in 1972–74".

He replaced several regional commanders with trusted officers and labeled his political programmes "abertura" (opening) and distensão (decompression), meaning a gradual relaxation of authoritarian rule.

[citation needed] Together with his Chief of Staff, minister Golbery do Couto e Silva, Geisel devised a plan of gradual, slow democratization that would eventually succeed despite threats and opposition from the hard-liners.

The expectation was that the combined effects of import substitution industrialization and export expansion eventually would bring about growing trade surpluses, allowing the service and repayment of the foreign debt.

As inflation and unemployment soared, the foreign debt reached massive proportions making Brazil the world's biggest debtor, owing about US$90 billion to international lenders.

The opposition vigorously struggled for passing a constitutional amendment that would allow direct popular presidential elections in November 1984, but the proposal failed to win passage in Congress.

These conceptual transformations were supported by the younger segments of Itamaraty (Ministry of External Relations), identified with the tenets of the Independent Foreign Policy adopted by country in the early 1960s.

This prerogative had already been defended previously, when the Brazilian government decided not to accept the validity of the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TNP) in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The strategic move was to try to expand the negotiation agenda by paying special attention to the diversification of trade relations, the beginning of nuclear cooperation, and the inclusion of new international policy themes.

The government participated in Operation Condor, which involved various Latin American security services (including Pinochet's DINA and the Argentine SIDE) in the assassination of political opponents.

To foster these innovations, in 1972 foreign minister Gibson Barboza visited Senegal, Togo, Ghana, Dahomey, Gabon, Zaïre, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Côte d'Ivoire.