Brenda Zlamany

[4][5][6][7] She gained attention beginning in the 1990s, when critics such as Artforum's Barry Schwabsky, Donald Kuspit and John Yau identified her among a small group of figurative painters reviving the neglected legacies of portraiture and classical technique by introducing confrontational subject matter, psychological insight and social critique.

[8][9][10][11] Her early portraits of well-known male artists, such as Chuck Close and Leon Golub, reversed conventional artist/sitter gender and power dynamics;[12][13][14] her later projects upend the traditionally "heroic" nature of portraiture by featuring underrepresented groups and everyday people.

[2][24][1] In 1984, Zlamany took advantage of a Jerome Foundation Fellowship and moved to New York City, working as a master printer with artists such as Julian Schnabel, Vija Celmins and Sol LeWitt, and making etchings at the Bob Blackburn Printmaking Workshop.

[8][11][19] John Yau and others connect her work, in sensibility if not style, back to figurative modernists such as Alice Neel, Otto Dix and Ivan Albright, contemporary painters like Vija Celmins, Chuck Close, Gregory Gillespie and Alex Katz that integrate elements of abstraction into representational work, and postmodern artists such as John Currin, Elizabeth Peyton and Lisa Yuskavage who have ushered in new, critical and democratic forms of portraiture in recent decades.

[11][10][37][38][14] Distinguishing her from artists that appropriate or parody classical technique, Donald Kuspit placed Zlamany amid a tendency he called "new Old Masterism" that sought "to restore the beauty lost to avant-garde innovation.

[43][48][49][50][51] Her 1995 show at Sabine Wachters featured portraits of the gallery's other artists—generally middle-aged, bald, male conceptual artists—that Guy Gilsoul called meticulously painted, inaccessible "mixtures of attraction, and repulsion, fascination and aversion.

"[47] In conceptual terms, critics such as Robert C. Morgan deemed this work a provocative deconstruction that coaxed "exemplars of art world virility"[13] into a passive role in order to glimpse male reality and sexual and power dynamics, reversing centuries of objectification of female subjects.

[55][34][54] They emphasized the minimal nature of Zlamany's work, which had long eschewed architecture and landscape elements and iconographic cues in favor of composition, proportion, ground color and manner of representation as means of conveying narrative or psychological content.

[56][33][7] Critics such as Donald Kuspit continued to note her confrontation with representational conventions and Old Master technique and devices in these works and the later Self-Portrait with Oona nursing (2003–4), a stark contemporary rendering of the Madonna and Child motif.

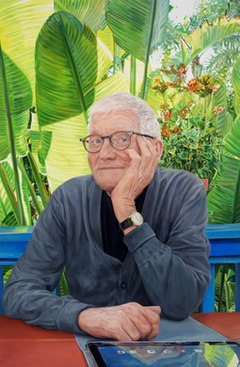

[7][19] Zlamany's international, multiyear project, "The Itinerant Portraitist" (2011– ), explores portraiture focused on nontraditional subjects: indigenous communities in Taipei, orphaned Emirati girls, taxicab drivers in Cuba, and nursing home residents in the Bronx.

[7][38] She produced portraits of Osama bin Laden (cover),[61] Slobodan Milosevic and Mirjana Marković,[62] Marian Anderson,[63] and Jeffrey Dahmer for special issues of The New York Times Magazine.