Bretton Woods system

The planners at Bretton Woods hoped to avoid a repetition of the Treaty of Versailles after World War I, which had created enough economic and political tension to lead to WWII.

Intransigent insistence by creditor countries for the repayment of Allied war debts and reparations, combined with an inclination to isolationism, led to a breakdown of the international financial system and a worldwide economic depression.

[8] The beggar thy neighbour policies that emerged as the crisis continued saw some trading countries using currency devaluations in an attempt to increase their competitiveness (i.e. raise exports and lower imports), though recent research[when?]

The U.S. was concerned that a sudden drop-off in war spending might return the its population to unemployment levels of the 1930s, and so wanted Sterling-using countries and everyone in Europe to be able to import from the US, hence the U.S. supported free trade and international convertibility of currencies into gold or dollars.

[13] When many of the same experts who observed the 1930s became the architects of a new, unified, post-war system at Bretton Woods, their guiding principles became "no more beggar thy neighbor" and "control flows of speculative financial capital".

Preventing a repetition of this process of competitive devaluations was desired, but in a way that would not force debtor countries to contract their industrial bases by keeping interest rates at a level high enough to attract foreign bank deposits.

... For a variety of reasons, including a desire of the Federal Reserve to curb the U.S. stock market boom, monetary policy in several major countries turned contractionary in the late 1920s—a contraction that was transmitted worldwide by the gold standard.

Moreover, the charter called for freedom of the seas (a principal U.S. foreign policy aim since France and Britain had first threatened U.S. shipping in the 1790s), the disarmament of aggressors, and the "establishment of a wider and more permanent system of general security".

[22] In addition, U.S. unions had only grudgingly accepted government-imposed restraints on their demands during the war, but they were willing to wait no longer, particularly as inflation cut into the existing wage scales with painful force (by the end of 1945, there had already been major strikes in the automobile, electrical, and steel industries).

[25][26] A senior official of the Bank of England commented: One of the reasons Bretton Woods worked was that the U.S. was clearly the most powerful country at the table and so ultimately was able to impose its will on the others, including an often-dismayed Britain.

At the time, one senior official at the Bank of England described the deal reached at Bretton Woods as "the greatest blow to Britain next to the war", largely because it underlined the way financial power had moved from the UK to the US.

Negotiators at the Bretton Woods conference, fresh from what they perceived as a disastrous experience with floating rates in the 1930s, concluded that major monetary fluctuations could stall the free flow of trade.

Further, a sizable share of the world's known gold reserves was located in the Soviet Union, which would later emerge as a Cold War rival to the United States and Western Europe.

Already in 1944, the British economist John Maynard Keynes emphasized "the importance of rule-based regimes to stabilize business expectations"—something he accepted in the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates.

Officially established on 27 December 1945, when the 29 participating countries at the conference of Bretton Woods signed its Articles of Agreement, the IMF was to be the keeper of the rules and the main instrument of public international management.

The big question at the Bretton Woods conference with respect to the institution that would emerge as the IMF was the issue of future access to international liquidity and whether that source should be akin to a world central bank able to create new reserves at will or a more limited borrowing mechanism.

Overall, White's scheme tended to favor incentives designed to create price stability within the world's economies, while Keynes wanted a system that encouraged economic growth.

Although a compromise was reached on some points, because of the overwhelming economic and military power of the United States the participants at Bretton Woods largely agreed on White's plan.

White’s plan was designed not merely to secure the rise and world economic domination of the United States, but to ensure that as the outgoing superpower Britain would be shuffled even further from centre stage.

[34] What emerged largely reflected U.S. preferences: a system of subscriptions and quotas embedded in the IMF, which itself was to be no more than a fixed pool of national currencies and gold subscribed by each country, as opposed to a world central bank capable of creating money.

[37] The United States set up the European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan) to provide large-scale financial and economic aid for rebuilding Europe largely through grants rather than loans.

In the long run it was expected that such European and Japanese recovery would benefit the United States by widening markets for U.S. exports and providing locations for U.S. capital expansion.

A trade surplus made it easier to keep armies abroad and to invest outside the U.S., and because other countries could not sustain foreign deployments, the U.S. had the power to decide why, when and how to intervene in global crises.

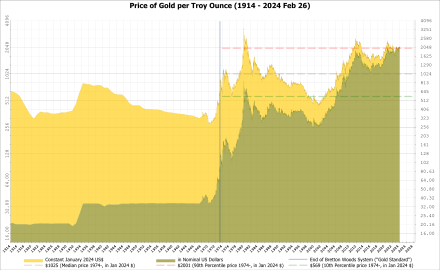

In 1960 Robert Triffin, a Belgian-American economist, noticed that holding dollars was more valuable than gold because constant U.S. balance of payments deficits helped to keep the system liquid and fuel economic growth.

[41] U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson was faced with a difficult choice, either institute protectionist measures, including travel taxes, export subsidies and slashing the budget—or accept the risk of a "run on gold" and the dollar.

This was followed by a full closure of the London gold market, also at the request of the U.S. government, until a series of meetings were held that attempted to rescue or reform the existing system.

With total reserves exceeding those of the U.S., higher levels of growth and trade, and per capita income approaching that of the U.S., Europe and Japan were narrowing the gap between themselves and the United States.

A negative balance of payments, growing public debt incurred by the Vietnam War and Great Society programs, and monetary inflation by the Federal Reserve caused the dollar to become increasingly overvalued.

In an attempt to undermine the efforts of the Smithsonian Agreement, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates in pursuit of a previously established domestic policy objective of full national employment.

As a result, the dollar price in the gold free market continued to cause pressure on its official rate; soon after a 10% devaluation was announced in February 1973, Japan and the EEC countries decided to let their currencies float.

In the early 1970s, this graph shows some currencies at fixed exchange rates before floating against each other: