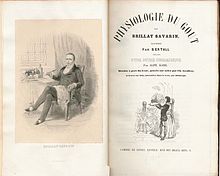

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

Published weeks before his death in 1826, the work established him alongside Grimod de La Reynière as one of the founders of the genre of the gastronomic essay.

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin was born on 2 April 1755 in the small cathedral city of Belley, Ain, 80 kilometres (50 miles) east of Lyon and a similar distance south of Bourg-en-Bresse.

Although founded as a religious institution and with many of its staff in holy orders, the college was secular in outlook; theology was not in the curriculum and the library contained works on agriculture and science as well as books by La Rochefoucauld, Montesquieu, Rabelais, Voltaire and Rousseau.

In 1787 he first visited the royal residence, the Château de Versailles; his purpose may have been to seek help for the poor of his region, but he left no details of his mission.

[11] Riots broke out in Grenoble in June 1788 in protest against the abolition of traditional and supposedly guaranteed local freedoms, and it became clear that effective government had so seriously collapsed that Louis XVI would have to summon a meeting of the Estates General, the closest approximation in Ancien Régime France to a national parliament; it had not met since 1614, and in the words of the historian Karen Diane Haywood it "generally met only in dire situations when the king and his ministers had no other choice".

[13] In a biographical sketch Anne Drayton observes "there was nothing of the revolutionary in his make-up", and when the Estates General reformed as the National Constituent Assembly he made speeches opposing the division of France into eighty-three administrative departments, the introduction of trial by jury and the abolition of capital punishment.

[13][14] At the end of his term of office in September 1791 Brillat-Savarin returned home as president of the civil tribunal of the new department of Ain, but as politics in Paris became increasingly radical, with the abolition of the monarchy, he was persona non grata with the new regime, and was dismissed from his post for royalist sympathies.

[15] For nearly a year he strove to protect his city from the excesses of the revolution, but when the Reign of Terror began in September 1793 he felt increasingly at risk of arrest and execution.

[15] He later had fond memories of his time in America: While staying with a friend in Hartford, Connecticut he shot a wild turkey[n 2] and brought it back to the kitchen: he wrote of the roast bird that it was, "charming to behold, pleasing to smell, and delicious to taste".

[22] One of his favourite memories of his American stay was an evening at Little's Tavern in New York when he and two other French émigrés beat two Englishmen in a competitive drinking bout, in which they all consumed large quantities of claret, port, Madeira and punch.

He continued to amuse himself with, among other diversions, what a biographer calls "undoubtedly numerous" encounters with the opposite sex;[24] Brillat-Savarin commented, "being able to speak the language and flirt with women, I was able to reap the richest rewards".

Drayton comments that by this time Brillat-Savarin had obviously acquired a certain reputation as a gourmet, "for he was promptly put in charge of catering for the general staff, a task which he performed to the delighted satisfaction of his fellow officers".

[30] After Napoleon Bonaparte engineered the fall of the Directory and establishment of the Consulate in 1799, Brillat-Savarin was appointed as a judge in the Tribunal de cassation, the supreme court of appeal, which sat in Paris.

[52] The longest section of the book is headed "Gastronomical Meditations", in which the author devotes short chapters to thirty topics, ranging from taste, appetite, thirst, digestion and rest to gourmands, obesity, exhaustion and restaurateurs.

[53] The second and smaller part of the main text consists of "Miscellanea", including many anecdotes on a gastronomic theme such as the bishop who mischievously presented his eager guests with fake asparagus made of wood, and memories of the author's exile.

[54] In addition to his magnum opus, Brillat-Savarin wrote works about law and political economy: Vues et Projets d'Economie Politique (Political Economy: Plans and Prospects) (1802), Fragments d'un Ouvrage Manuscrit Intitulé Théorie Judiciare (Fragments of a work in manuscript entitled "Legal Theory") (1818), and a study of the archaeology of the Ain department (1820).

[42] He also wrote a history of duelling, and what Drayton calls "a number of rather racy short stories, most of which are lost", although one, Voyage à Arras, remains extant.

"[62] By his choice of title Brillat-Savarin seems to have been responsible for a temporary change in French writers' use of the word physiologie, although he himself used it literally, in the sense of "a scientific analysis of the workings of living beings".

Charlton adds that Brillat-Savarin transmutes cooking, "which Plato had despised as a mere 'routine'", into philosophy, shaming Descartes and Kant in his meditations on, respectively, "Dreams" and "The End of the World".