British Bangladeshis

[8] Other early records of arrivals from the region that is now known as Bangladesh are of Sylheti cooks in London during 1873, in the employment of the East India Company, who travelled to the UK as lascars on ships to work in restaurants.

[9][10] The first educated South Asian to travel to Europe and live in Britain was I'tisam-ud-Din, a Bengali Muslim cleric, Munshi and diplomat to the Mughal Empire who arrived in 1765 with his servant Muhammad Muqim during the reign of King George III.

The man was waited upon by the Prime Minister of Great Britain William Pitt the Younger, and then dined with the Duke of York before presenting himself in front of the King.

Job opportunities were initially limited to low paid sectors, with unskilled and semi-skilled work in small factories and the textile trade being common.

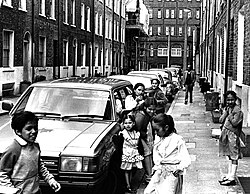

[28] The period also however saw a rise in the number of attacks on Bangladeshis in the area, in a reprise of the racial tensions of the 1930s, when Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts had marched against the Jewish communities.

White youths known as "skinheads" appeared in the Brick Lane area, vandalising property and reportedly spitting on Bengali children and assaulting women.

Parents began to impose curfews on their children, for their own safety; flats were protected against racially motivated arson by the installation of fire-proof letterboxes.

[21] On 4 May 1978, Altab Ali, a 24-year-old Bangladeshi leather clothing worker, was murdered by three teenage boys as he walked home from work in a racially motivated attack.

[21][34] In 1986, the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee's race relations and immigration sub-committee conducted an inquiry called Bangladeshis in Britain.

The evidence also noted issues of concern to the Bangladesh community, including "immigration arrangements; relationships with the police (particularly in the context of racial harassment or attacks); and the provision of suitable housing, education, and personal, health and social services".

[93] There had been unsuccessful attempts by a fringe group during the 1980s to recognise Sylheti as a language in Tower Hamlets, which lacked much support from the community as most favoured standard Bengali to be taught in "mother tongue" classes.

[98] Standard Bengali maintains its prominence in British Bangladeshi media and is considered as a prestige language which helps to foster a cultural or national identity linked with Bangladesh.

[119][120] The Economist has argued that the lack of a second income in households was "the main reason" why many Bangladeshi families live below the poverty line and the resulting high proportion reliant on welfare payments from the government.

[121] According to research by Yaojun Li from the University of Manchester in 2016, while the employment rate of Bangladeshis has improved and the proportion of women in work has risen by one-third in the last five years, it is still weaker than educational performance.

However, this is not reflected or translating in labour market outcomes because although young people from Bangladeshi backgrounds are more likely to "succeed in education and go to university," they are less likely to go on to "find employment or secure jobs in managerial or professional occupations."

[128] In November 2015, an Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) report said that Bangladeshi children living in the UK have a nearly 49 per cent higher chance on average of a university education than white British pupils.

[21][140] Research suggests that British Bangladeshis need intervention to prevent diabetes at a body mass index (BMI) of 21, which is lower than the otherwise recommended threshold.

[100] The 2001 census for England and Wales found that only 37% of Bangladeshis owned households compared to 69% of the population, those with social rented tenure is 48%, the largest of which in Tower Hamlets (82%) and Camden (81%).

[146][147] British Bangladeshis are around three times more likely to be in poverty compared to their white counterparts, according to a 2015 report entitled 'Ethnic Inequalities' by the Centre for Social Investigation (CSI) at Nuffield College at University of Oxford.

The event is broadcast live across different continents; it features a funfair, music and dance displays on stages, with people dressed in colourful traditional clothes, in Weavers Field and Allen Gardens in Bethnal Green.

[153] As of 2009, the Mela was organised by the Tower Hamlets council, attracting 95,000 people,[154] featuring with popular artists such as Momtaz Begum, Nukul Kumar Bishwash, Mumzy Stranger and many others.

[190][198] There are many other entrepreneurs, including the late Abdul Latif, known for his dish "Curry Hell"; Iqbal Ahmed, placed at number 511 on the Sunday Times Rich List 2006, and celebrity chef Tommy Miah.

[217] Nationalism is mainly witnessed during celebrations of the mela, when groups such as the Swadhinata Trust try to promote Bengali history and heritage amongst young people, in schools, youth clubs and community centres.

The underlying assumption was that "Englishness" was associated with "whiteness" whereas "Britishness" denoted a more universal kind of identity that encompasses various cultural and racial backgrounds.

[54] As a response to conditions faced by their first generation elders during the 1970s (see history), younger Bangladeshis started to form gangs, developing a sense of dominating their territory.

Bangladeshi teenagers involved with gangs show their allegiance to this kind of lifestyle in various ways: heavily styled hair, expensive mobile phones and fashionable labels and brands.

As to dietary customs, youths generally avoid eating pork, and some from drinking alcohol; however, many take part in recreational drug use,[224] in particular heroin.

[240] In 2008, Guild of Bangladeshi Restaurateurs members raised concerns that many restaurants were under threat because the British Government announced a change in immigration laws which could block entry of high skilled chefs from Bangladesh to the UK.

The situation has worsened due to a yearly salary minimum of £35,000 applied to tier 2 migrants, or skilled workers with a job offer in the UK, coming into effect April 2016.

For a large number of families in Britain the cost of living, housing, or education for the children severely constrains any regular financial commitment towards Bangladesh.