British comics

The stock media phrase "real 'Roy of the Rovers' stuff" is often used by football writers, commentators and fans when describing displays of great skill, or surprising results that go against the odds, in reference to the dramatic storylines that were the strip's trademark.

In British comics history, there are some extremely long-running publications such as The Beano and The Dandy published by D. C. Thomson & Co., a newspaper company based in Dundee, Scotland.

[6] The collection featured The Beano, The Dandy, Eagle, The Topper, Roy of the Rovers, Bunty, Buster, Valiant, Twinkle and 2000 AD.

Full of close-printed text with few illustrations, they were essentially no different from a book, except that they were somewhat shorter and that typically the story was serialised over many weekly issues in order to maintain sales.

And to pad out a successful series, writers would insert quite extraneous material such as the geography of the country in which the action was occurring, so that the story would extend into more issues.

Stories featuring criminals such as 'Spring-Heeled Jack', pirates, highwaymen (especially Dick Turpin), and detectives (including Sexton Blake) dominated decades of the Victorian and early 20th-century weeklies.

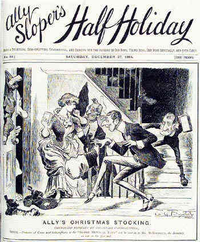

Writer Denis Gifford considered Funny Folks to be the first British comic,[7] though at first it tackled topical and political subjects along the same lines as Punch.

The magazine was heavily illustrated, with cartoons by John Proctor, known as Puck, among others,[8] and benefitted from innovations in the use of cheap paper and photographic printing.

The problem which now faces society in the trade that has sprung up of presenting sadism, crime, lust, physical monstrosity, and horror to the young is an urgent and a grave one.In the early 1950s, "lurid American 'crime' and 'horror comics' reached Britain", prompting what in retrospect has been characterised as a moral panic.

[15] Copies of Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror, which arrived as ballast in ships from the United States, were first only available in the "environs of the great ports of Liverpool, Manchester, Belfast and London", but by "using blocks made from imported American matrices", British versions of Tales from the Crypt and The Vault of Horror were printed in London and Leicester (by companies like Arnold Book Company)[16] and sold in "small back-street newsagents.

"[15] The ensuing outcry was heard in Parliament, and at the urging of the Most Reverend Geoffrey Fisher, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Major Gwilym Lloyd George, the Home Secretary and Minister of Welsh Affairs, and the National Union of Teachers, Parliament passed the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act 1955.

[17] The act prohibited "any book, magazine or other like work which is of a kind likely to fall into the hands of children or young persons and consists wholly or mainly of stories told in pictures (with or without the addition of written matter), being stories portraying (a) the commission of crimes; or (b) acts of violence or cruelty; or (c) incidents of a repulsive or horrible nature; in such a way that the work as a whole would tend to corrupt a child or young person into whose hands it might fall.

At the end of the 1960s, these comics moved away from gravure printing, preferring offset litho due to cost considerations arising from decreasing readership.

They found themselves in the same market as teenage titles for girls such as Boyfriend and Blue Jeans, which had changed their content and were featuring mainly product-related articles and photo comics.

So much so that in 1976 the parent company briefly published a minimal amount of new material specifically for the UK market in Captain Britain.

The American reprint material proved to be more successful and continued to appear into the 1980s, at which stage Marvel UK also began diversifying into home-produced original material, both UK-originated strips featuring American created characters such as Captain Britain, the Hulk and the Black Knight, and wholly original strips like Night Raven.

[citation needed] However, both these comics ceased publication soon after their trial, as much due to the social changes at the end of the counter-culture movement as any effect of the court cases.

Published by DC Thomson, it proved to be a success, and led to its then-rival, IPC Magazines Ltd, producing Battle Picture Weekly, a comic notably grimmer in style than its competitor.

In 1978 The Adventures of Luther Arkwright by Bryan Talbot began serialisation in Near Myths (and continued in other comics after that title folded).

[26] In 1982 Dez Skinn launched Warrior, possibly the most notable comic of the period, as it contained both the Marvelman and V for Vendetta strips, by Alan Moore.

Based upon bad taste, crude language, crude sexual innuendo, and the parodying of strips from The Dandy (among them Black Bag – the Faithful Border Bin Liner, a parody of The Dandy's Black Bob series about a Border Collie), the popularity of Viz depended entirely upon a variant of Sixties counter-culture; and it promptly inspired similarly themed titles, including Smut, Spit!, Talking Turkey, Elephant Parts, Gas, Brain Damage, Poot!, UT and Zit, all of which failed to achieve Viz's longevity and folded, while Viz remained one of the United Kingdom's top-selling magazines.

[28] An ever-increasing number of small press and fanzine titles are being produced, such as Solar Wind or FutureQuake, aided by the cheapness and increasingly professional appearance of desktop publishing programs.

[32] However, thanks to the strong sales for Briggs' Ethel and Ernest, and Jimmy Corrigan winning The Guardian's best first novel award, publishers have started expanding into this area.

[31] There are a number of new publishers who are specifically targeting this area,[33] including Classical Comics[34][35] and Self Made Hero, the latter having an imprint focused on manga adaptations of the works of Shakespeare.

The DFC launched at the end of May 2008 drawing together creators from the small press and manga, as well as figures from mainstream British comics and other fields,[39] including author Philip Pullman.

After World War II, the UK was intent on promoting homegrown publishers, and thus banned the direct importation of American periodicals, including comic books.

When Captain Marvel ceased publication in the United States because of a lawsuit, L. Miller & Son copied the entire Captain Marvel idea in every detail, and began publishing their own knock-off under the names Marvelman and Young Marvelman, taking advantage of different copyright laws.

The British publishers reprinted many other American series, including the early 1950s Eerie and Black Magic in black-and-white format.

Igor Goldkind was Titan's (and Forbidden Planet's, which was owned by the same company) marketing consultant at the time; he helped popularise the term "graphic novel" for the trade paperbacks they were releasing, which generated a lot of attention from the mainstream press.

Simultaneously, the very small press Fanfare/Ponent Mon published a few UK-exclusive English-language editions of alternative Japanese manga and French bande dessinée.

January 6, 1940 edition.

12 October 1963.

26 February 1977.