Coronation of the British monarch

The service ends with a closing procession, and since the 20th century it has been traditional for the royal family to appear later on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to greet crowds and watch a flypast.

While retaining the most important elements of the Anglo-Saxon rite, it may have borrowed from the consecration of the Holy Roman Emperor from the Pontificale Romano-Germanicum, a book of German liturgy compiled in Mainz in 961, thus bringing the English tradition into line with continental practice.

[4] Following the start of the Reformation in England, the boy king Edward VI had been crowned in the first Protestant coronation in 1547, during which Archbishop Thomas Cranmer preached a sermon against idolatry and "the tyranny of the bishops of Rome".

The original rituals were a fusion of ceremonies used by the kings of Dál Riata, based on the inauguration of Aidan by Columba in 574, and by the Picts from whom the Stone of Destiny came.

The ceremony was held in a church, since demolished, within the castle walls and was conducted by the Bishop of Glasgow, because the Archbishop of St Andrews had been killed at the Battle of Flodden.

His son Charles I travelled north for a Scottish coronation at Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh in 1633,[15] but caused consternation amongst the Presbyterian Scots by his insistence on elaborate High Anglican ritual, arousing "gryt feir of inbriginge of poperie".

[23] George's brother and successor William IV had to be persuaded to be crowned at all; his coronation at a time of economic depression in 1831 cost only one sixth of that spent on the previous event.

[26] When Victoria was crowned in 1838, the service followed the pared-down precedent set by her uncle, and the under-rehearsed ceremonial, again presided over by William Howley, was marred by mistakes and accidents.

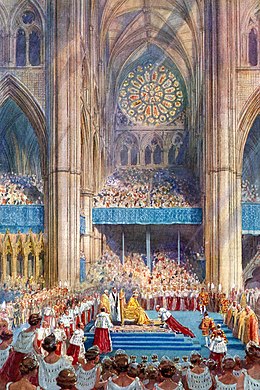

[28] In the 20th century, liturgical scholars sought to restore the spiritual meaning of the ceremony by rearranging elements with reference to the medieval texts,[29] creating a "complex marriage of innovation and tradition".

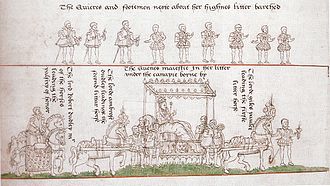

[31] The idea of the need to gain popular support for a new monarch by making the ceremony a spectacle for ordinary people, started with the coronation in 1377 of Richard II who was a 10-year-old boy, thought unlikely to command respect simply by his physical appearance.

For the coronation of William IV and Adelaide in 1831, a state procession from St James's Palace to the abbey was instituted, and this pageantry is an important feature of the modern event.

[35] Re-enactments of the ceremony were staged at London and provincial theatres; in 1761, a production featuring the Westminster Abbey choir at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden ran for three months after the real event.

This would prevent television viewers from seeing most of the highlights of the coronation, including the actual crowning, live; it led to controversy in the press and even questions in parliament.

By 1937, the Statute of Westminster 1931 had made the dominions fully independent, and the wording of the coronation oath was amended to include their names and confine the elements concerning religion to the United Kingdom.

Elizabeth II was asked, for example: "Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?

In 1821, George IV's estranged wife Caroline of Brunswick was not invited to the ceremony; when she showed up at Westminster Abbey anyway, she was denied entry and turned away.

[78] Elizabeth I was crowned by the Bishop of Carlisle (to whose see is attached no special precedence) because the senior prelates were "either dead, too old and infirm, unacceptable to the queen, or unwilling to serve".

Since the coronation of Richard I in 1189, the Bishops of Bath & Wells and Durham have assumed this duty.Custom has it that they accompany the monarch throughout the ceremony, flanking them as they process from the entrance of Westminster Abbey and standing either side of St Edward's Chair during the anointing.

The legal claim of the Scholars of Westminster School to be the first to acclaim the monarch on behalf of the common people was formally disallowed by the court, but in practice their traditional shouts of "Vivat!

Although the service has undergone two major revisions and a translation, and has been modified for each coronation for the following thousand years, the sequence of taking an oath, anointing, investing of regalia, crowning and enthronement found in the Anglo-Saxon text[94] have remained constant.

[43] Since the Glorious Revolution, the Coronation Oath Act 1688 has required, among other things, that the sovereign "Promise and Sweare to Governe the People of this Kingdome of England and the Dominions thereto belonging according to the Statutes in Parlyament Agreed on and the Laws and Customs of the same".

[99] The oath has been modified without statutory authority; for example, at the coronation of Elizabeth II, the exchange between the Queen and the archbishop was as follows:[43] The Archbishop of Canterbury: Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?

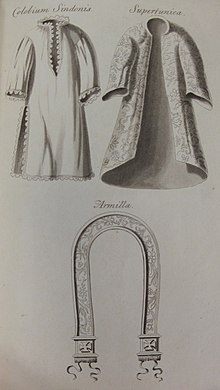

The Dean of Westminster pours consecrated oil from an eagle-shaped ampulla into a filigreed spoon with which the Archbishop of Canterbury anoints the sovereign in the form of a cross on the hands, head, and heart.

[112] When this prayer is finished, the choir sings an English translation of the traditional Latin antiphon Confortare: "Be strong and of a good courage; keep the commandments of the Lord thy God, and walk in his ways".

In the past peers then proceeded to pay their homage, saying "I, N., Duke [Marquess, Earl, Viscount, Baron or Lord] of N., do become your liege man of life and limb, and of earthly worship; and faith and truth will I bear unto you, to live and die, against all manner of folks.

The sovereign then dons the Imperial State Crown and takes into their hands the Sceptre with the Cross and the Orb and leaves the chapel first while all present sing the national anthem.

Compositions by Thomas Tallis, Orlando Gibbons and Henry Purcell were included alongside works by contemporary composers such as Arthur Sullivan, Charles Villiers Stanford and John Stainer.

This was approved by the Queen and the Archbishop of Canterbury, so Vaughan Williams recast his 1928 arrangement of Old 100th, the English metrical version of Psalm 100, the Jubilate Deo ("All people that on earth do dwell") for congregation, organ and orchestra: the setting has become ubiquitous at festal occasions in the Anglophone world.

For those in attendance (other than members of the royal family) what to wear is laid down in detail by the Earl Marshal prior to each Coronation and published in The London Gazette.

After 1800, the form for this was as follows:[140] If any person, of what degree soever, high or low, shall deny or gainsay our Sovereign Lord ..., King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, son and next heir unto our Sovereign Lord the last King deceased, to be the right heir to the Imperial Crown of this Realm of Great Britain and Ireland, or that he ought not to enjoy the same; here is his Champion, who saith that he lieth, and is a false traitor, being ready in person to combat with him; and in this quarrel will adventure his life against him, on what day soever he shall be appointed.